Camera traps & wildlife in the park

Wildlife research in our community: Tracking native species & habitat connectivity

Overview

Dr. David Stokes and his research team conducted a two-year camera trap study to better understand wildlife presence, habitat connectivity and human disturbance at Saint Edward State Park.

Using 31 cameras deployed across 35 locations, the study recorded over 7,500 occurrences of 18 different mammal species, including both native and non-native animals. The research combined spatial analysis and behavioral observations to examine how species interact with the park’s diverse forest habitats and human activity.

Why study wildlife in our urban parks?

The urban parks in our community, like Saint Edward State Park, serve as critical refuges for wildlife. However, habitat fragmentation, invasive species and human activity can threaten the biodiversity these parks support.

Dr. Stokes’ research provides key insights into:

- Which species are living within the park

- How human activity affects wildlife behavior

- The role of habitat connectivity in supporting biodiversity

Key findings

Camera traps revealed a rich diversity of wildlife that before this study were not caught on camera, including bobcats, coyotes and river otters, confirming a healthy predator population. Previously undocumented species, also included a Townsend’s chipmunk and a flying squirrel,

Interior habitats support native wildlife:

- Bobcats and Douglas squirrels were found to prefer undisturbed interior forest areas.

- Coyote and raccoon populations were more adaptable and present throughout the park.

- Riparian forests (forests along rivers and streams) and lakeshores hosted the highest number of species.

Human disturbance influences wildlife behavior:

- Animals near trails and park edges were more nocturnal than those in interior habitats.

- Domestic cats, predators to native species, and non-native rats were almost exclusively found near the park’s edge.

- Wildlife activity was highest in areas with limited human access.

Building on the research

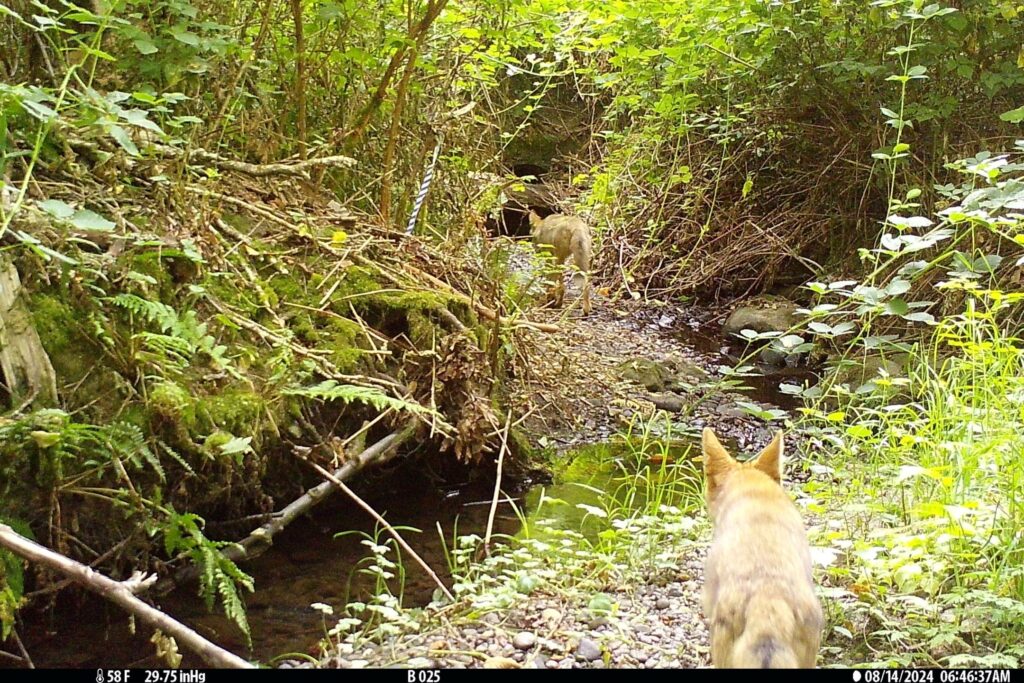

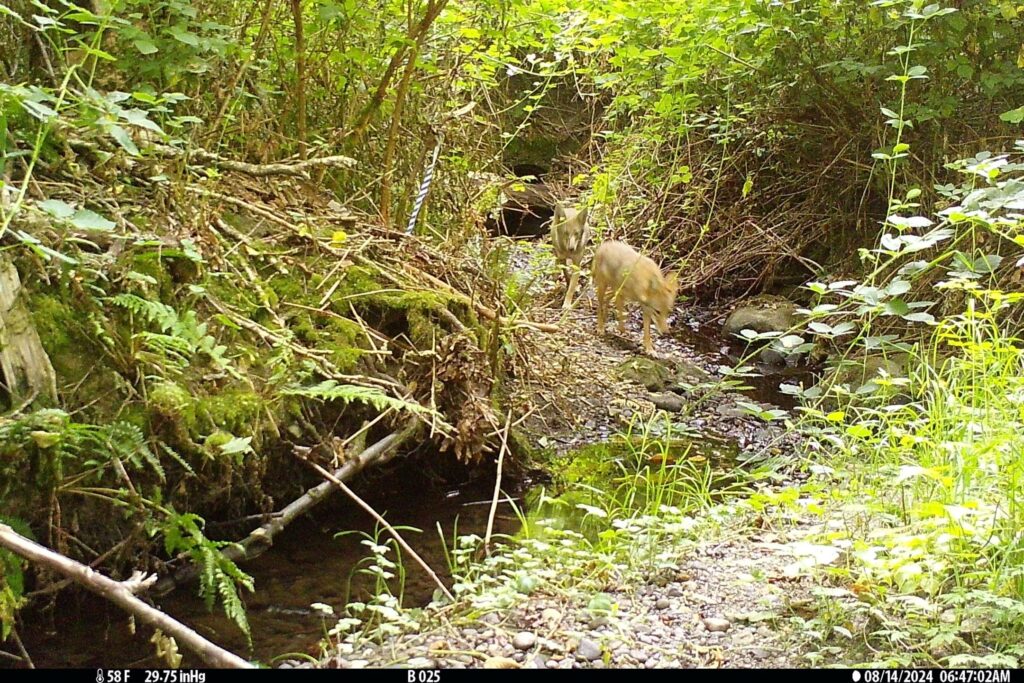

Ash Putzke’s wildlife study in collaboration with Finn Hill Neighborhood Alliance (FNHA)

The work of Dr. Stokes and his team has inspired ongoing research nearby. UW Bothell student Ash Putzke, in collaboration with the Finn Hill Neighborhood Alliance (FHNA) and Dr. Stokes, is using cameras deployed on upper Denny Creek near Big Finn Hill Park to understand what species are present and how they are interacting with the culvert, (define/ describe culvert).

As a part of their environmental science capstone project, Ash investigated two questions:

- What animals are present in a disturbed riparian habitat east of Juanita Drive?

- Does Juanita drive act as a barrier, and is the Denny Creek culvert used to pass under Juanita drive?

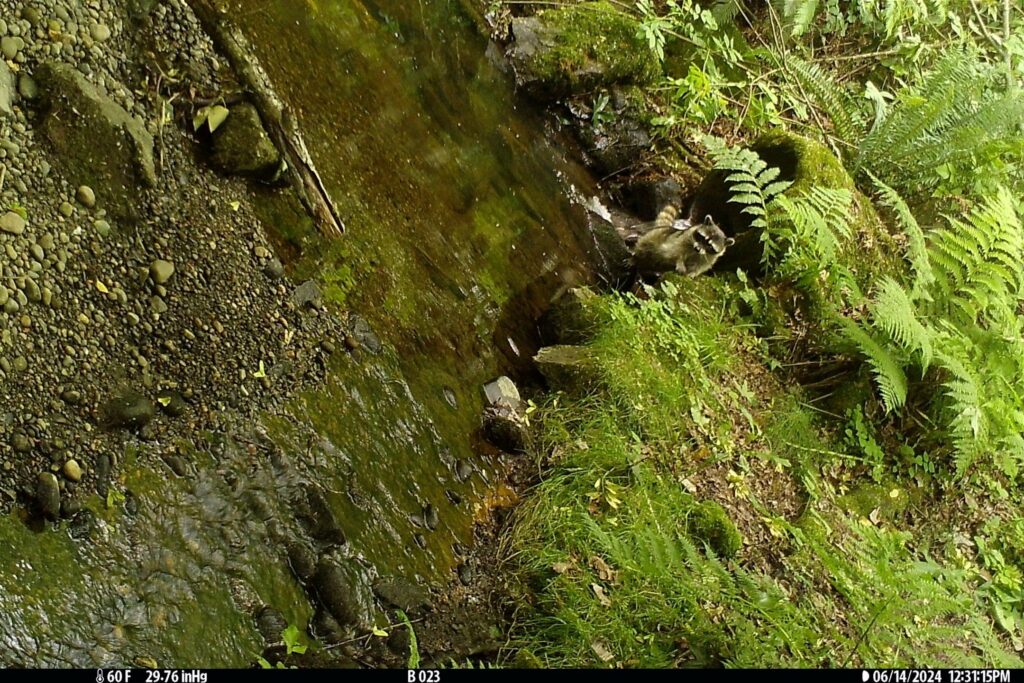

After reviewing one year of data, Ash discovered that at least 18 native species use the disturbed habitat, including mammals like the river otter, coyote, raccoon, bobcat, and deer, and birds like the pileated woodpecker, rufous hummingbird and red-tailed hawk. They also found that raccoons would use the culvert to cross, while coyotes turned around more often (sometimes trying the culvert but never seen successfully crossing using the culvert). Juanita Drive and the Denny Creek Culvert may also be a barrier to beavers, which were seen to the west of Juanita Drive but never on the east side.

“I’m excited to discover that even small pipe culverts offer some habitat connectivity, but this research shows that it may not be enough. We can use culvert research to understand how building and replacing culverts won’t only benefit salmon if we consider and design for how they can improve connectivity for the whole forest community.”

This project highlights that there is habitat value in degraded land. Access to this land may be limited by roads, and small culverts might not provide a good alternative crossing.