When Ayomikun Akinrinade was 8 years old, his mom sent him to an engineering summer camp. She thought it would be a great way to get her son involved in the community and to give herself a few kid-free hours in the day, too. What neither she nor Akinrinade could have expected was the impact it would have on his future.

One of the camp activities involved building cars out of wooden blocks and attaching CO2 canisters to act as engines. From the moment Akinrinade saw his makeshift car take off, he was hooked. “I remember asking the camp leader what job I should get if that’s what I wanted to do when I grew up,” he said. “She told me I should be a mechanical engineer so up until I was 18 and started college that was what I wanted to become.”

Until he realized what really motivates him is learning how to think like a scientist.

Spaceships & sea creatures

His first science class at the University of Washington Bothell in 2018 was Introduction to Biology. He remembers it so well that he even recalls the day and time of the class three years later. “Mondays and Wednesdays at 8:45 — I absolutely loved it,” he said.

He especially loved the way the class challenged him to ask questions people don’t yet have answers for and then finding innovative solutions. “I went from wanting to understand how to build a spaceship to wanting to understand evolution in fish,” he said. “It sounds very different, but the way of thinking is the same.”

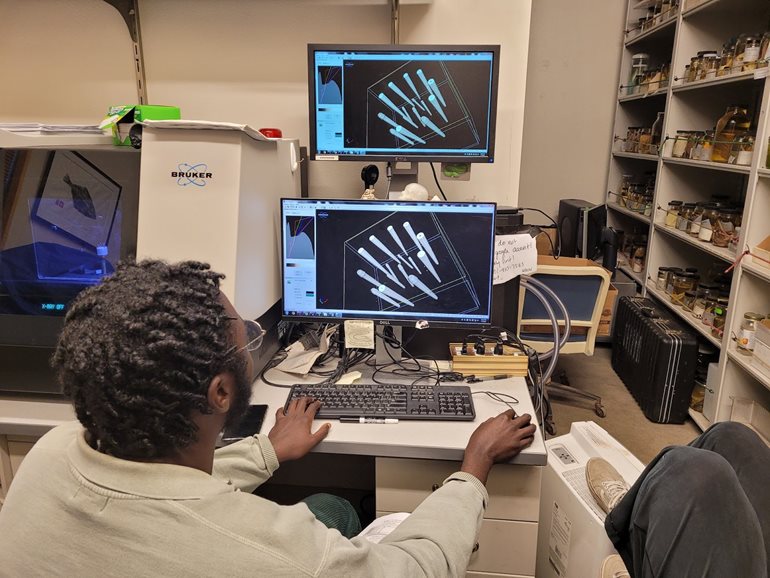

This realization launched his undergraduate research career. And in summer 2021, he was one of only 12 students selected to study at the UW’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, a marine science research facility in the San Juan Islands.

Faculty and researchers from UW and around the world come to FHL to study oceanography, chemistry, biology, ecology and other marine disciplines. Akinrinade was part of the REU-Blinks Summer Internship Program, which links undergraduate students with scientist-mentors as collaborators in marine science research.

Science & skills building

Dr. Jeffrey Jensen, teaching professor in UW Bothell’s School of STEM, encouraged Akinrinade to take advantage of the opportunity to work with such distinguished scientists. “My students who make it to Friday Harbor describe it as life changing and the best summer of their life,” he said.

Akinrinade spent eight weeks on an outpost in the middle of the Salish Sea with other undergraduate students who share a similar passion for marine biology. His fellow researchers came to study at FHL from California, Florida, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York and South Dakota. Just as Jensen suspected, it was the best two months of Akinrinade’s life. “It was such a supportive and incredible group of people that I got to learn alongside of,” Akinrinade said. “I had the most amazing time.”

He spent the summer researching the biomechanics of sea urchin spines, wanting to learn how effective they are at puncturing skin. “Otters are natural predators of sea urchins,” he said, “and I wanted to measure the amount of force it would take to break the skin in an otter’s mouth — and how much energy it takes to dig further in after the initial puncture.”

In his research, he looked at purple, pale and green sea urchins, all native to the Puget Sound. He compared how effective each urchin’s spine was at breaking into gelatin, the substance he used to act in place of skin from a predator’s mouth. He then obtained the data on the necessary force by using a material testing system.

“It was great learning how to use the MTS,” Akinrinade said. “Knowing how to operate the machine widens the possibilities of research. It is such a valuable skill.”

Surprises & surgeons

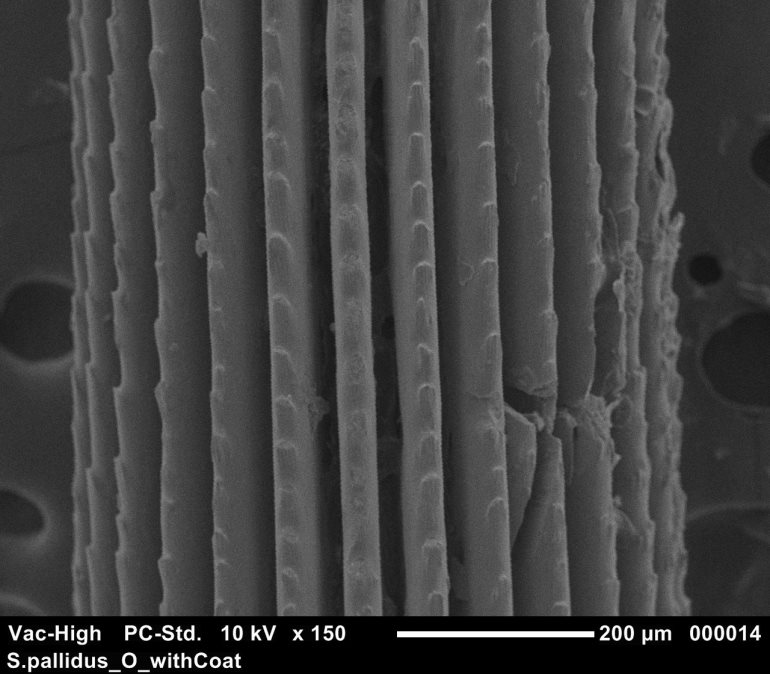

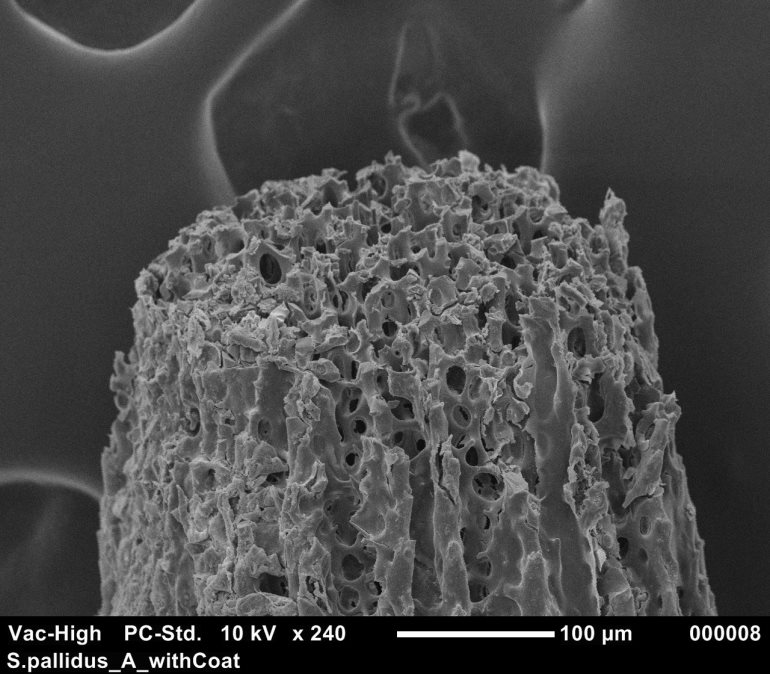

That, however, was just part of what Akinrinade did over the summer. He also looked at the morphology of the sea urchin’s spine, in other words its size, shape and structure. “This was my favorite part of the research. I expected each spine to look the same, but they were different,” he said. “I love being surprised by science.”

The variation is found in the serrations. Some urchins have ridges and furrows while others do not. “This was odd because it was something I definitely thought would be consistent,” Akinrinade said. “I imagine the serrations could be used to make puncture easier.”

He also believes that these findings could have important benefits to the medical community. “All scientific discoveries that we have applications for started with basic science like this,” he said. “This provides the groundwork for others to do more advanced research.”

Further analysis on the serrations of sea urchin spines could help develop more effective equipment, for example. “If surgeons need to make puncture easier, they could use different ridges and furrows on their needle,” Akinrinade said. “It is amazing what one small discovery can lead to.”

Studies & support

Guiding him throughout the research process was Dr. Stephanie Crofts, assistant professor in the biology department at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts. “It was really fun working with Ayomikun this summer and seeing him grow as a researcher,” Crofts said. “What stood out to me was his drive to learn as much as possible, tackling all sorts of cool tools and techniques.”

Akinrinade closed out the summer by presenting his research to his cohort, family and friends, where he thanked UW Bothell for making him the scientist he is today.

“Every faculty member I have met at the University has pushed me to become more than what I came in as,” he said. “My professors have been so supportive and really looked out for me. They gave me the confidence to apply to graduate schools.”

Akinrinade, a senior majoring in Health Studies and minoring in Biology, recently started applying to colleges to earn a doctorate in Biology. He then plans to become a professor, work in a fish and wildlife program in the Pacific Northwest or work as a museum curator.

“I don’t know exactly what the future holds,” he said, “but I do know that I am excited for wherever it takes me.”