By Douglas Esser

Kokanee, the freshwater-only cousins of ocean-going sockeye, once filled the streams flowing into Lake Washington. Now the little red fish are gone from the lake. Or are they?

Ichthyologist Jeff Jensen, a senior lecturer at the University of Washington Bothell, is studying some fish that are kokanee-like.

“Is this some still self-supporting separate population of original kokanee? That seems kind of unlikely,” Jensen said. “Could these be new kokanee that evolved from introduced sockeye or maybe from introduced kokanee?”

Still other possibilities are early-returning sockeye or sockeye known as residuals that skip migrating to the ocean. Playing off the scientific name for sockeye, Oncorhynchus nerka, Jensen uses the Dr. Seuss-sounding name of “snerka” to describe small nerka of uncertain affinities.

Free natural history

Jensen will share his research Oct. 29 at McMenamins in Bothell with a free public lecture called “The Mysterious ‘Snerka:’ The Curious History, Current Status and Future Prospects of Local Kokanee.”

The mystery is more than an academic question.

“Ultimately what I would like to do is restore kokanee runs to a bunch of streams, especially in Lake Washington that historically had large runs of kokanee but now have none at all,” Jensen said.

Many factors likely contributed to the demise of kokanee in Lake Washington, but major reductions coincided with the 1916 opening of the Hiram Chittenden locks. The direct connection between Lake Washington and Puget Sound favored sockeye that were introduced.

Some native kokanee do survive in Lake Sammamish, near Issaquah.

130-year-old fish

Amazingly, a few Lake Washington kokanee that were collected as samples in the 1880s are still around, preserved in alcohol. Jensen has specimens on loan from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and a scientific collection at Stanford University. That the fish were preserved in alcohol, instead of formaldehyde, is important for genetic testing. DNA extraction is easier, thus allowing comparison to potential descendants.

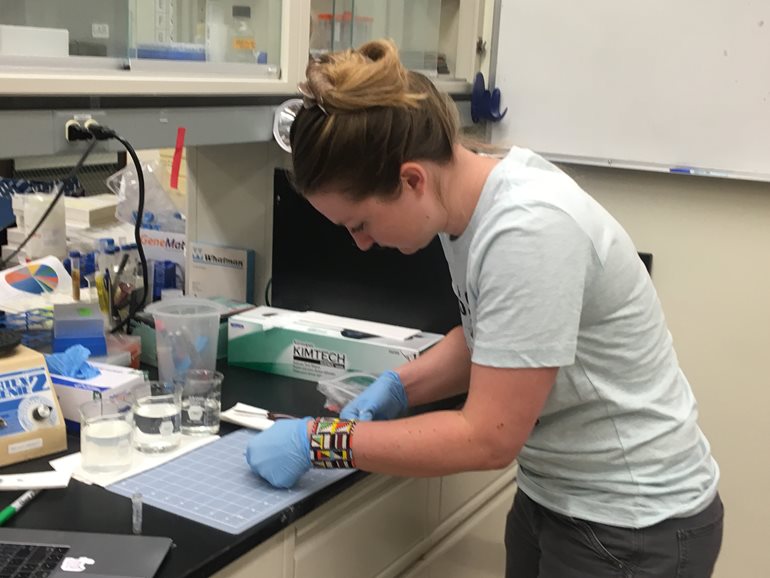

Testing of current and old fish took place last summer at a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration conservation genetics lab in Seattle where Jensen is associated. One of his Biology students in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics, Jodi Signer, conducted some of the work with the lab’s Eric Iwamoto, an expert in extracting fish DNA.

“This is not always easy as the specimens do not always work in the first trial because the fish are so old,” said Signer, a senior who is continuing the research this quarter.

Signer also has counted kokanee fry at Laughing Jacobs Creek, a tributary of Lake Sammamish near Issaquah.

“Working alongside Dr. Jensen has opened my eyes to the true endangerment some of these species are facing as well as the resilience they still have,” she said.

Doing it right

Jensen hopes the genetic information from fish that swam more than a century ago will help him figure out how modern populations of kokanee are related.”In the process of doing that, I’m looking at these mystery snerka and seeing where they fit.”

Eventually, Jensen hopes to return kokanee or kokanee-like fish to Lake Washington streams using remote site incubators that he’s developed and tested with his students. Two creeks — Lyon and McAleer — are likely sites in Lake Forest Park, where Jensen is involved in the Lake Forest Park Stewardship Foundation. Another possibility is North Creek, which runs through the UW Bothell campus.

Mystery snerka might do reasonably well in one of these streams with minimal risk, he said. “They’re already in Lake Washington so I don’t have to worry about transferring genes or diseases from one place to another.”

He must take care to avoid problems such as building a population that might threaten the kokanee in Lake Sammamish, which is connected to Lake Washington by the Sammamish River. Anything affecting waterways and fish requires oversight and permits on the county, state, federal and tribal levels.

Destination: Restoration

It will take time, but little red fish might once again fill Lake Washington creeks, Jensen hopes.

“I would love to have kokanee everywhere, because they were at one time around here,” he said.

Salmon restoration in general — and kokanee restoration in particular — is a great way to rally the community around restoring habitats, Jensen said. It offers a tangible goal for a sign of success.

“If you were to go down to your stream and see sockeye or kokanee in there,” he said, “that’s going to have a bigger impact on you in terms of whether you get your oil leak fixed in your car or use pesticides on your lawn or destroy habitats or vegetation around a stream.”