By Douglas Esser

Walking around the University of Washington Bothell and Cascadia College campus, students and visitors will notice some plants have name tags with more than a name.

The tagged plants, mostly located near the Sarah Simonds Green Conservatory, are labeled with QR codes. Through the interactive technology, the plants can now tell their own stories.

See it, read it

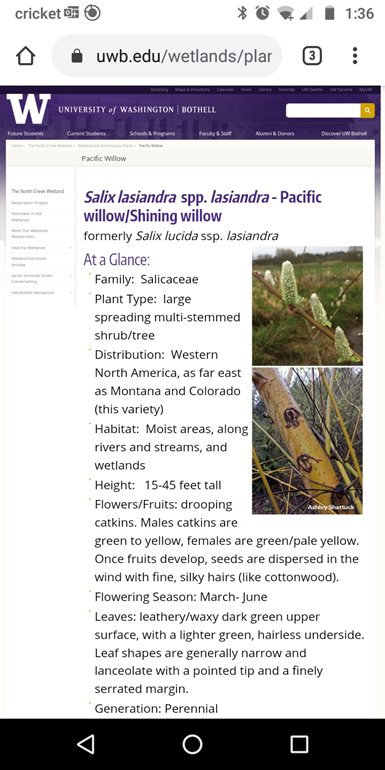

A QR code is a square matrix of dots that works with a smartphone like a bar code crossing a checkout counter scanner. Simply pointing a smartphone camera at the QR code opens a browser, and a webpage appears with detailed information. The QR interactivity is built into most iPhones and can be installed with a code reader app on Android phones.

So, when you see a bush on campus and its “red elderberry” tag, just pull out your phone, center the QR code on the camera screen, and a second later you’re reading, “Commonly known as red elderberry, Sambucus racemosa, is widely dispersed in the United States…”

Sarah Verlinde, a specialist in the UW Bothell Office of Research who volunteers as managesr of the UW Bothell Herbarium, came up with the idea of a QR code plant walk or tour. She implemented it, as her time allowed, over several years with the help of Tyson Kemper, the grounds supervisor and herbarium curator, plus students and volunteers.

Bothell ethnobotany

There are nearly 50 plants in the system. Staking a nametag in the ground was the easiest part. Most of the work went into researching and compiling site-specific information. That information also can be accessed through the wetlands website. Verlinde and her team created the content, with special attention to the traditional knowledge and practical uses of plants by indigenous people.

“We included a lot of ethnobotany. Sometimes that’s hard to find,” Verlinde said. “If available, we wanted to make sure we included how local tribes, like the Skagit, Snohomish and Salish, used these plants.”

Looking at the knowledge base and a plant simultaneously, visitors also can see how it could be used in restoration and the benefits for wildlife and the environment.

Some of the tags are on tropical plants, such as the insect-eating pitcher plant, in the greenhouse, which isn’t normally open to the public. But, most of the tagged plants are outside: around the Conservatory, next to the nearby trail on the edge of the wetlands, and near the Activities & Recreation Center and the campus bus stop.

Verlinde wanted the plant tour to be available to members of the public who might be visiting campus or walking by on the trail. “They can interact with this space without anybody being here, which is really nice,” she said.

Verlinde selected native perennials for most of the plants on the tour. Many are shrubs or trees that are present year-round. A few die back during the winter.

Resource for students

The QR tags are a practical benefit for students taking environmental classes in the wetlands that involve plant identification. “Now you have a sure ID,” said Jessica Rouske, who had several courses that used the wetlands.

“I think this gives them students a wider array of plants, and you can learn more about our native species, which I think is super important for all sorts of different courses,” said Rouske, a herbarium volunteer who continued volunteering after graduating in 2019 in Biology.

Audrey Figgins, who is graduating in June in Environmental Studies, volunteered on the herbarium project as the community-based learning part of an Environmental Issues course. The experience raised her interest in botany and deepened her appreciation of the wetlands.

“I understand the space differently now — what kinds of native plants we have here,” said Figgins, who would like to work as an environmental reporter.

In the future, Verlinde hopes the campus will create a brochure mapping all the plants on the tour. She’d also like to see the number of QR tags expanded to more plants on campus, such as the Food Forest along the Promenade.

There are many more plants with stories to tell.