By Maria Lamarca Anderson

Neither snow and ice nor lack of heat nor suspended campus operations could stay the University of Washington Bothell faculty from supporting the success of their students.

Unlike K-12 schools, the university doesn’t have the option to go beyond the scheduled last day of the quarter — and yet students still need to learn all the material on course syllabi.

So when it appeared the forecast of a major snowstorm (or two) might result in cancelled classes for several days starting Feb. 4, faculty began making arrangements to ensure students would not fall behind. They adjusted lesson plans and rescheduled midterm exams. Some even adjusted content and pedagogy so that they could conduct class remotely.

Experimenting with new tools

“Our department has very few hybrid or online classes so for many faculty, this was a new situation,” said Jennifer McLoud-Mann, professor and chair of the Division of Engineering and Mathematics in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Math (STEM). “They knew little about the software they were about to use.”

A number of faculty turned to Panopto to record lectures at home. Using the cameras on their computers, they filmed themselves talking while simultaneously illustrating concepts on pieces of paper, a far cry from the large, erasable whiteboards they use in the classroom.

Using Panopto required certain equipment, and those who hadn’t used the software before were at somewhat of a disadvantage, said McLoud-Mann. “But that didn’t stop them. Emails flew back and forth about what people needed and who might be able to help,” she said. “In the end, they made their way to each other’s houses to pick up and drop off equipment.

“They didn’t expect their students to travel in those conditions, yet they didn’t hesitate to put themselves out there,” she said. “I truly appreciate their determination.”

Thinking on their feet

On Thursday, Feb. 7, Nicole Hoover, a lecturer in STEM who teaches calculus and pre-calculus, sent her students home with a packet of work “just in case” and told them she would videotape the accompanying lecture and post it online. At that point they’d already missed two days of class.

“I decided to print it out because I knew some of them didn’t have the capability at home,” she said. “Plus, what if they lost power?”

It turned out that it was Hoover herself who had to work without electricity as she prepared her video lecture. She had been without power since the night before, and her laptop battery was running low. And it was just 56 degrees in her house.

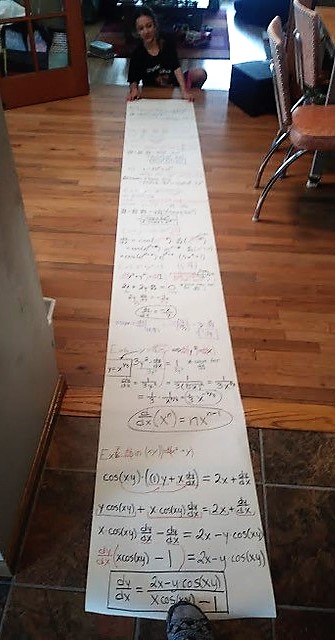

Undaunted, Hoover found a roll of butcher paper from her daughter’s school activities and enlisted her help writing out math problems that aligned with the paper packet she had given her students. She then used an old easel to demonstrate the calculations as her laptop camera recorded her entire lecture.

Next, she had to upload the video so students could access it online. “I used the hotspot on my husband’s phone to upload,” said Hoover. “I was nervous that the battery for either the phone or the laptop would drain before it was complete.”

A mathematician, she could not help but turn the situation into another math challenge, plotting a graph of the upload and the corresponding battery percentage. The video finished processing at 17 and 15 percent of the battery life for the phone and computer, respectively. “It just made it.”

But there was still more to be done. She used the last of the battery power to post instructions for her students to watch the video, follow along with the examples in their packets, and email her any questions.

Virtually in the same room

The next day, power restored, Hoover was able to check on her students’ progress online. Fewer than half had yet to watch the video. Knowing it would be difficult for them to catch up if they didn’t stay on top of the snow-day assignment, she posted another announcement reminding them about an upcoming quiz. In the end, most of the students watched the video and successfully worked through the math problems.

“It actually worked better to have this particular topic — chain rule — on video,” Hoover said. “It helped some to be able to watch it more than once.”

As for her own learning, Hoover said, “the situation forced me to learn new tools that I didn’t have time for before. It’s comforting to know that if I get sick and can’t come to class, I can still teach.”

Gavin Doyle, a lecturer in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences (IAS), and Charity Lovitt, a lecturer in STEM, co-teach “Atoms in Art and Culture.” They decided to hold class on Feb. 12 at its usual time using Zoom, a videoconferencing tool that neither of them had used extensively — and Doyle was without electricity until 30 minutes before class.

At the beginning of the lesson, almost all of their 44 students were able to log in, some sharing the same computer.

In the virtual classroom environment, the two faculty took turns lecturing, then created breakout “rooms” for student discussion groups. As online host of the space, Lovitt could go back and forth between the rooms to monitor and guide discussions. The students could ask questions through a group chat feature and shared their work using virtual whiteboards.

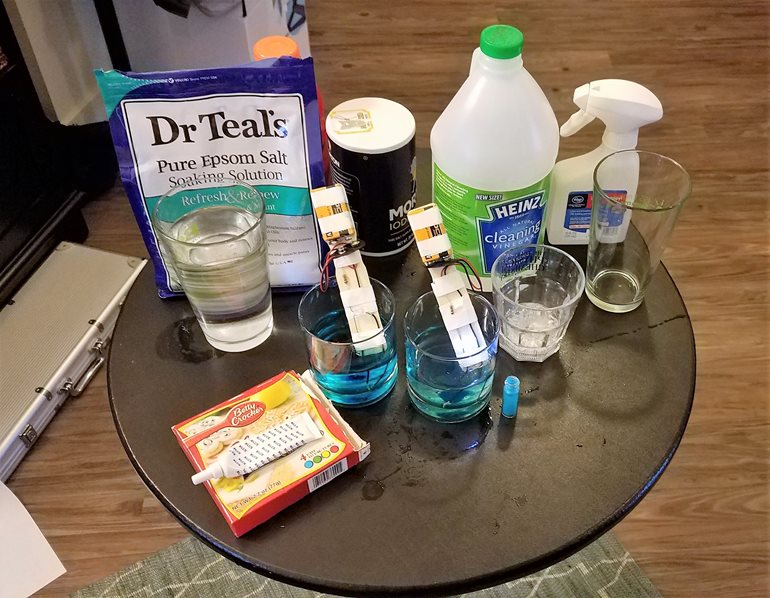

Lovitt also managed to conduct a chemistry experiment for students from her home using common household products. She gave the students formulas and tasked them with determining if the experiment would work.

Lessons learned

“It was a learning experience for both our students — who were introduced to the concepts we’d planned to discuss and were challenged to work collaboratively in virtual groups — and for us,” Doyle said.

“We had to figure out quickly how to do online polls, chat streams, videos, uploads and small group discussions,” he said. “When all was said and done, there were things we could do differently, but overall we’re pleased with how it all worked out for our students.”

Based on the success of the Feb. 12 virtual class, Doyle and Lovitt held another on Feb. 14, the seventh day of suspended operations. The classes were recorded so students could watch the videos if they couldn’t log in during class.

For her part, Assistant Professor Shannon Cram was scheduled to be in Eastern Washington for a meeting the week of Feb. 11 so her IAS students were already prepared to come to class as usual and proceed without her. Because of the snow, she wasn’t able to get to her out-of-town meeting but wanted to communicate with her students and be available if they had any questions.

Living in rural Duvall, she was without power for stretches at a time. She began her days walking a mile in the snow just to get cell service and find out if classes were canceled that week. She would then go home, make contingency plans, and then walk back later to send group announcements.

“I wanted them to know my status,” said Cram. “I didn’t want them to feel ignored. I also wanted to tell them to be cautious, especially if they chose to drive. Some of them couldn’t afford to miss work so they were out on the roads.”

Stronger going forward

McLoud-Mann said that faculty did all they could ensure their students could continue learning and not miss assignments.

“They scheduled makeup exams, offered remote sessions and held online office hours,” she said. “They spun a tough situation into an opportunity to learn.”

And while the threat of snow may be gone, the lessons learned are still making a difference in how some faculty approach the challenge of teaching.

“It’s made them excited about wanting to collaborate more,” she said. “There have been many discussions since about how they’re going to share best practices and continue learning from one another.”