Many nurses in the University of Washington Bothell Master of Nursing leadership track already are working in management roles and have years of clinical experience, but no one was quite prepared for the coronavirus pandemic.

In the final months of the program, they had to step up to finish school projects, pivot rapidly to fieldwork focused on COVID-19 and draw on their coursework and experience to respond to the escalating health crisis.

Nurses detailed their responses in their spring quarter MN Symposium presentations. The symposium is always an impressive arena for students’ innovative work and dedication, said Dean Shari Dworkin. In this year of rapid change and ambiguity, she said, nursing leaders demonstrated extra persistence, generosity and courage.

Celinda Smith, graduate program adviser, hosted the two-day event June 10 and 11 by teleconference with students, faculty advisers and community partners. Here are stories from five of the nursing leaders.

Maintaining trust

Tracy Marie Wellington had worked more than a decade as a nurse and supervisor at a Seattle hospital when she had the opportunity a year ago to become clinical director for a kidney center that provides dialysis services for eight hospitals.

It was Feb. 29 when she learned that someone they had been caring for the previous week had died of COVID-19.

“I knew at that moment that my approach to this crisis as a leader had to be transparent and consistent for my team to feel supported and to maintain the trust I had gained over the past year,” she said.

She had to tell the staff they had been exposed to COVID-19 and to send members home for a 14-day quarantine.

“It was an extremely challenging time for me as a leader — the fears, the tears and anxieties were real and understandable,” she said. At one time 20% of her team was quarantined.

“It was all-consuming for weeks on end.”

COVID-19 also exposed health care inequities, said Wellington, who has worked as an advocate for populations that are underserved. She collaborated with others through the Washington Center for Nursing to promote addressing social determinants of health and ending disparities. She also submitted testimony to the Seattle City Council for housing assistance for homeless people.

National guidance

Jennifer Tyner has years of experience as a director of nursing for a dialysis service with hundreds of patients. Like Wellington, Feb. 29 was the day she learned her staff had treated a COVID-19 patient who died.

Immediately, she threw herself into learning as much as possible about the impact of the coronavirus on the dialysis community. She became a member of a COVID-19 incident command team and communicated with her managers with a “focus on reducing fear with accurate knowledge from reliable sources.”

She also became part of an industry group that advised the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “It was mind-blowing that we were creating national guidance in real time,” she said.

As a result of that experience Tyner said she has a lot more confidence.

“I will use these skills to impact my management team and improve care safety,” she said.

Crucial communication

Tracey Jaeger is the clinical nurse liaison for a health care management company with several nursing homes. She had been teaching a course on palliative care as her fieldwork when she needed to make a fast change. She had to create COVID-19 policies for personal protective equipment for the staff and rules for visiting the homes, which quickly became no visits.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has put us through the ultimate test, forcing us to remain strong, focused and courageous leaders for our teams,” she said, adding that communication and relationship management were crucial.

The pandemic also revealed the shortage of resources for long-term care facilities. Private rooms would have prevented the virus spread, Jaeger said. Prioritizing elders would have kept them out of emergency rooms.

“This is the most emotional work I have ever done,” Jaeger said. “The last three months of this real-life fieldwork opportunity have taught me more about my ability to communicate effectively and lead high-performing teams.”

Providing leadership

Born in Ethiopia, Saba Tilahun learned English at a community college and has worked for years as a nurse in various specialties. As a charge nurse at a Seattle hospital, Tilahun was confident in her clinical skills but wanted to build her leadership skills with a master’s degree from UW Bothell.

Part of her fieldwork was to implement a program for nurses to serve as education champions within their own units. That was cut short when the coronavirus pandemic hit, and everyone responded to the emergency.

“I veered away from the pilot program to provide leadership on COVID-19 prevention and control programs,” she said.

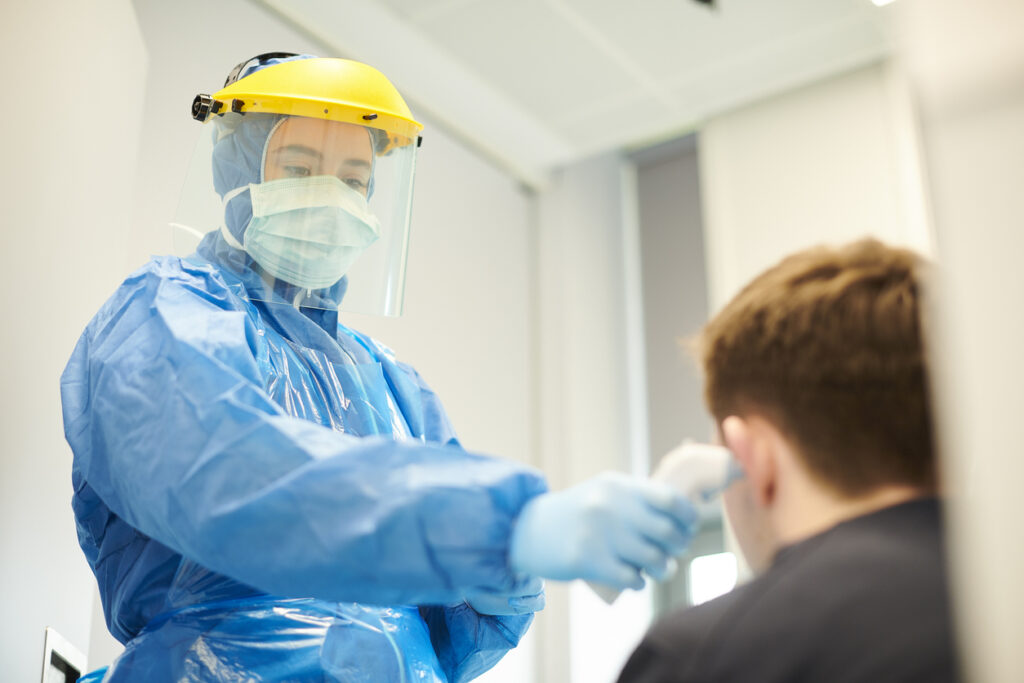

Tilahun was involved in infection prevention and control, focusing on isolation techniques. That included educating the staff on evolving policies for personal protective equipment and how to don and remove equipment in the safest sequence. She also educated the staff on screening arriving patients, swab collection and reporting symptoms.

One of the things she learned from the experience was the importance of building rapport with the staff to reduce their anxiety. “I learned how the knowledge of the health care environment is critical to being a nurse leader,” she said.

Combating inequality

Keith Koga, who received his Bachelor of Science in Nursing from UW Bothell in 2006, is a clinical assistant nurse manager at a Seattle hospital where he helped plan and implement drive-through and mobile COVID-19 testing clinics.

“As a nurse leader in the age of COVID-19, I’m committed to making processes within the health care system more efficient, so that these resources can be used to equalize health care access and combat social injustices,” he said.

Koga used skills in strategic planning and workflow diagramming that he learned in courses to plan the drive-through clinic. Once that was running, he was asked to help start a mobile testing group, which targets homeless people. A second van followed, targeting the immigrant population.

“The pandemic is disproportionately affecting the underserved and vulnerable,” he said, “and it has become evident to me that now more than ever is the time for nurse leaders like myself to step up and fight for those being affected by this virus.

“The skills I have learned during my journey at UW Bothell will allow me to be a part of my organization’s fight for justice and equality in this age of COVID-19.”

Advancing careers

U.S. News & World Report ranks the UW No. 2 among public schools that offer a master’s degree in nursing. The leadership track in the School of Nursing & Health Studies stands out as a partnership with the School of Business, which adds MBA courses on finance, organizational behavior and project planning. In addition to the leadership MN there is a general track and a nurse educator track.

Many nurses pursue a master’s degree to develop competencies they need or may be required to have to advance in their organizations. The School of Nursing & Health Studies trains nurse leaders to bridge the gap between policy and practice with added responsibility for institutional change, quality, communication and supporting the staff through times of change. In addition, the school prepares its graduates to advance diversity, equity and inclusion in their organizations and work to reduce health disparities.

In their symposium presentations, MN students said they learned competencies such as process improvement, relationship management, systems-thinking and using evidence-based data to inform decisions, improve care, and advance social justice and health.

Before it was the year of the coronavirus pandemic, 2020 was the International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife, as designated by the World Health Organization. Now, it seems prophetic.