By Douglas Esser

A scientific compendium of dried plants housed at the Sarah Simonds Green Conservatory is now listed on the world’s largest index of such collections, known as herbaria.

The UW Bothell Herbarium was recently accepted as part of the Index Herbaria, which includes 3,400 herbaria with 350 million botanical species. Maintained by the New York Biological Garden, it’s a research resource documenting earth’s biodiversity of plants and fungi.

On the world map

“Being listed in the Index puts us on the map for being an official herbarium,” said Sarah Verlinde, the collections manager. “From here, doors open for collecting permits from state and federal lands, and being able to compete for grants and sponsored programs.”

Getting the herbarium established is important for research, said Tyson Kemper, its curator and the campus lead gardener. UW Bothell is now part of a global exchange of information and specimens.

“If I have a student wanting to study strawberries, and I only have three species in my herbarium,” Verlinde said, “then I can contact New York or Florida or New Zealand and have them send me their strawberry specimens.”

Likewise, the UW Bothell Herbarium is a resource for ecologists around the world who could use it in studies that might include biodiversity, invasive species or climate change. An herbarium serves as a lab, library and museum. It’s not a seed bank, but botanists are using leaf tissues from specimens more than 100 years old for DNA and protein analysis.

A small offshoot

Compared to most collections, the UW Bothell Herbarium is small with about 1,000 plants. About 200 were collected from the North Creek wetlands, which were restored from farmland when the campus was established.

The 58-acre area was scraped bare in 1997 as the creek was diverted back to a meandering path. All the plants growing there now have been planted or spread by birds, breeze or water like cattail fluff, Verlinde said.

With its focus on the wetlands, the UW Bothell Herbarium also provides a record of habitat change in one of the region’s biggest floodplain restoration projects. About 80 percent of the wetlands’ plants are included in the herbarium, Verlinde estimates. Kemper has a backlog he’s working on, as he has time, to correctly identify the plants.

Branching out

Most other plants in the UW Bothell Herbarium come from around King and Snohomish counties. A large number are specimens shared by the Otis Douglas Hyde Herbarium at the UW Center for Urban Horticulture. They include many plants from the Washington Park Arboretum in Seattle and the King County Noxious Weeds Collection. Most of the UW Bothell Herbarium plants are visible online through the Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria.

Caren Crandell, now a lecturer in the UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, planted the seed for the herbarium 10 years ago when she taught ecology classes in UW Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences (IAS). The herbarium moved into the Sarah Simonds Green Conservatory when it opened in 2013. About 100 plants had been cataloged when Verlinde (Biology ’15) started collecting specimens as Crandell’s student in 2014.

Verlinde now works as a launch specialist in the UW Bothell Office of Research and has been expanding the herbarium with Kemper and volunteer Ashley Shattuck (Environmental Studies ’15).

Growing interest

The official herbarium — and several binders full of duplicate plants — are used in academic courses. They include environmental classes taught by Ursula Valdez, a lecturer in IAS. They also include ecology and research classes taught by Cynthia Chang, an assistant professor in the Division of Biological Sciences in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics. Some specific courses are Environmental Issues, Plant Ecology and Ecological Methods.

Verlinde also enlists students in community-based learning and research classes, plus botany-loving volunteers. To add plants to the herbarium from Snohomish County where she lives, Verlinde leads students on collecting trips around the county, including the 1,300-acre Lord Hill Park, near the city of Snohomish.

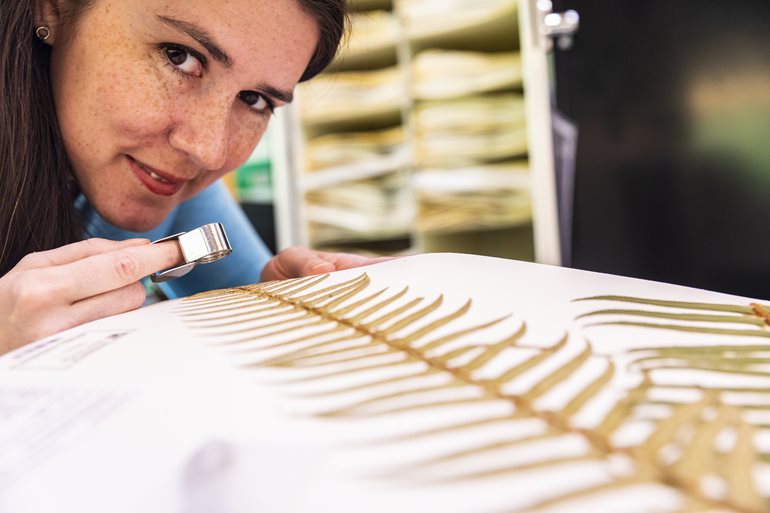

Collecting, identifying, preserving

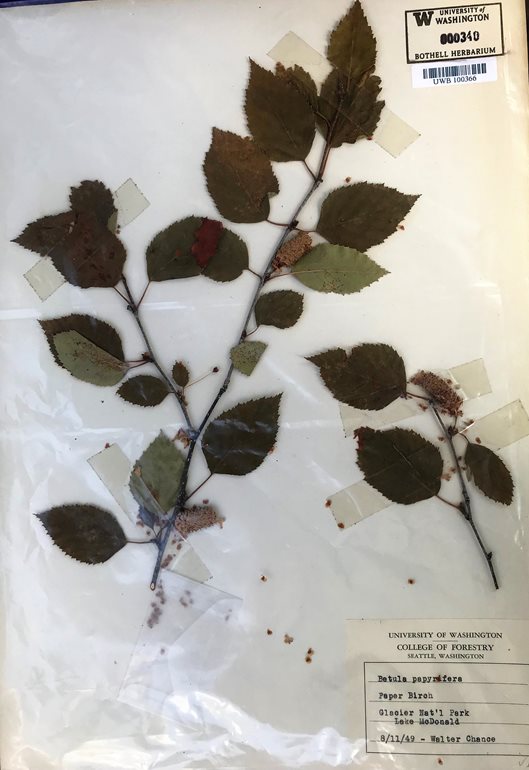

When a plant is collected, it immediately goes into a press to dry flat, which will preserve it. After a few weeks, it is then carefully laid out and glued to a cardstock page to show the fronts and backs of leaves and other parts. They often create an artistic composition. Before joining the herbarium, a plant spends 48 hours in a freezer to kill bugs, Kemper said.

An important part of the page is the documentation that goes on the label, available online. That includes a description of the plant — family, genus and species — where it was found with GPS coordinates and habitat description.

While looking at a specimen several years old, Verlinde said, “I can tell that we’re at North Creek and that there were willows and alders growing there. We can go back and see how these areas have changed over time.”

Verlinde sees a lot of growth ahead for the herbarium, adding plants from the region and increasing academic access. “This is the beginning of something great.”

To review the specifications for the UW Bothell Herbarium on the Index Herbarium, enter the code UWB. To view the published collection in the Consortium of Northwest Herbaria, search under Specimen Database with the fields Vascular Plants and UWB checked.