By Douglas Esser

University of Washington Bothell research into the hormone DHEA and aggression in songbirds indicates the hormone alters regions of the brain that regulate social behavior. That could have implications for people who take DHEA as a health supplement.

The peer-reviewed paper by Douglas Wacker, assistant professor of animal behavior in the School of STEM biological sciences division, has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Neuroendocrinology and released online.

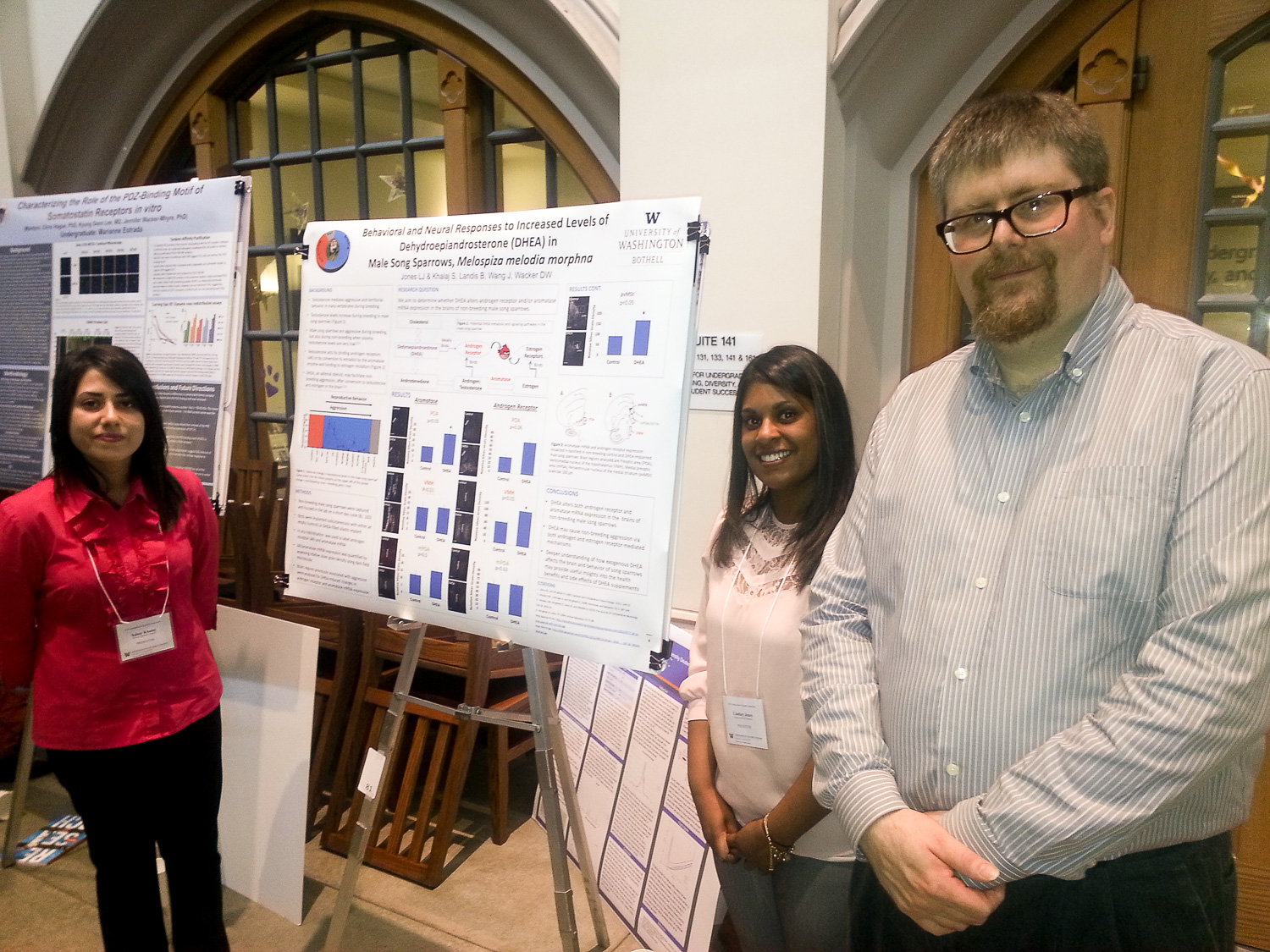

Wacker says he couldn’t have completed the paper without the help of two former students, Lindsey J. Jones and Sahar Khalaj, who are co-authors. They “stuck with it” after they were introduced to the research in a class, B BIO 495, Investigative Biology, Wacker says. Both graduated in 2014 with degrees in biology.

“It’s their dedication to the project and working on it after the class that got us where we are today,” Wacker says.

The research involves the hormone DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone), which is produced in the adrenal gland and found in blood. It can be turned into testosterone and estrogen in the brain. Wacker’s previous research with song sparrows in 2008 showed that DHEA increased aggression. The new research shows that DHEA changes brain chemistry and aggressive behavior at the same time.

DHEA is sold over the counter as a health supplement to build muscle, fight aging and increase sex drive. The performance enhancing drug is banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency as an anabolic androgenic steroid. It’s legal, but users are advised to check with a physician because of side effects.

Aggression in male song sparrows varies seasonally. By implanting DHEA into the birds, watching their behavior and later analyzing their brains, the researchers were able to say the hormone leads to aggressive behavior directly or by conversion to estrogen or testosterone.

For the research, male song sparrows (Melospiza melodia morhpna) collected in western Washington had the hormone implanted for two weeks. Their behavior was observed in cages on the Seattle campus. When an aggressive bird saw or heard an intruder next to its home cage (territory), it would display aggression by singing, pointing at the intruder, fluffing its feathers or spreading its tail.

Later, the students looking at the birds’ brains under microscopes at UW Bothell found that brain changes likely contributed to the aggression. That DHEA alters steroid-sensitive regions has significance beyond bird brains, says Wacker.

“If I was a body builder or a patient taking DHEA, I’d want to know this information,” he says.

Wacker, who also is known for his research in communication among the thousands of crows that roost in the UW Bothell wetlands, says the songbird research contributes to what’s known about how hormones affect the brain and social behavior. Long-term DHEA use has the potential to change neural networks in the brain, Wacker says.

Khalaj says the research project opened opportunities. She is now a third-year medical student with the Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences working rotations at Skagit Valley Hospital in Mount Vernon.

“Dr. Wacker was an amazing teacher and a great mentor, and it was an honor to work with him,” Khalaj says.

Jones says researching regions of the brain was an amazing and challenging experience.

“Dr. Wacker provided a great mentorship in dealing with unexpected results,” says Jones. “Having my name as a co-author on this paper is an honor, and I feel a sense of completeness in following through until the end.”

The songbird research was done in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh and funded in part by National Science Foundation grants.