By Douglas Esser

Three researchers in a Commons Hall (UW2) lab are working this summer with plastic bags of mushroom mycelium oozing enzymes, containers of fungi-filled sawdust filtering water samples and straw-filled burlap mats crawling with the white filaments of fungi growth. They are working on a way to remove bacteria from water, using the campus wetlands as their test site. (Marc Studer lab photos)

Under the guidance of Rob Turner, senior lecturer in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, Kellen Maloney, David Jackson and Saiwa Conejo believe that enzymes created by mushrooms' mass of tiny root-like mycelium destroy bacteria, such as E. coli.

Roosting crows get some of the blame in the wetlands, but E. coli bacteria are a common problem in any waterway polluted by wastes from wild animals, cows or failed septic systems.

The burlap mats look like the booms or tubular wattles commonly used at construction sites to slow or catch sediment in runoff. The idea is to seed them with mushrooms and then put the fungi mats in parts of the 58-acre wetlands to filter water before it reaches North Creek, eliminating the fecal bacteria.

The team has been measuring how long the water needs to be in contact with the mats to kill E. coli. In one test, pouring wetland stream water through a mushroom sawdust medium reduced E. coli by 50 percent. Keeping it in contact for an hour increased that to 67 percent. And 24-hour contact removed 99.97 percent of the E.coli bacteria. Photo: Kellen Maloney with beaker of enzymes.

The researchers are so engaged in their progress they’re volunteering their time this summer – unpaid and for no college credit. Of course, they believe it will pay off in the long run in their professional development. It’s also exciting to work on something with the potential to help solve water pollution problems beyond Bothell.

Maloney, who won a $750 Founders Fellow research scholarship in January, graduated in June in environmental science. He finds time to return to campus despite a full-time job. Jackson is working to graduate next June in environmental studies and is thinking of graduate school. Conejo wasn’t sure of her major until she became involved in the project and is working to graduate in 2018 in environmental science.

“I’ve always been interested in the environment, but this narrowed my focus,” she says.

Jackson became hooked on the research after a spring quarter project.

“That experiment was challenging enough and frustrating enough for me that I loved the fact that I was doing it,” he says. “When summer came and we all sat down and decided what we were doing I decided, this is it. I decided to stick with it – too much fun.”

Maloney feels the excitement of discovery.

“For me it’s a lot like exploring – new knowledge,” he says. “To understand that knowledge that’s on our own earth, in our natural environment, is something I’m really passionate about.”

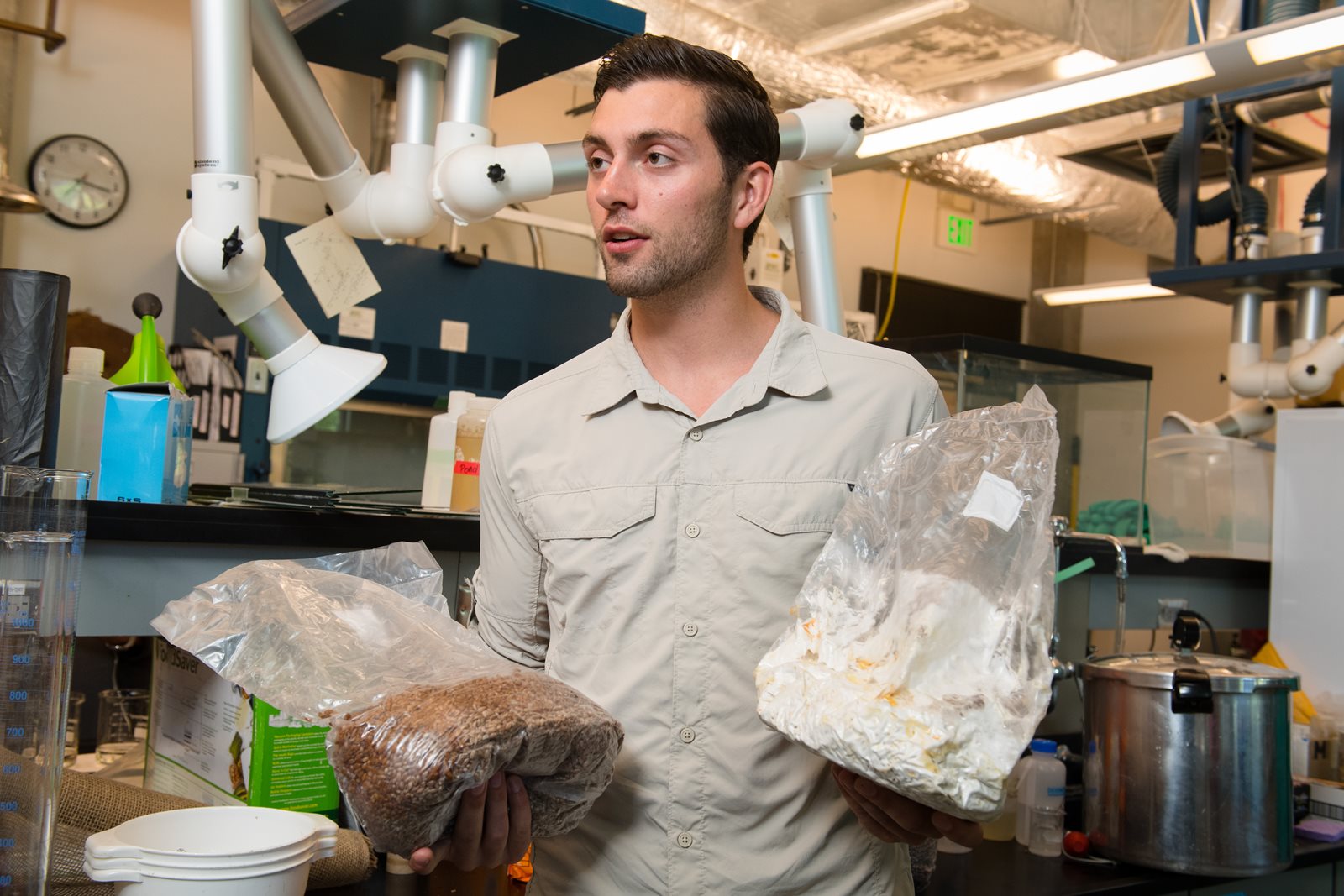

Photo: Kellen Maloney with bag of growth medium and bag infused with white mycelium.

Turner says his students have been conducting the research mostly on their own and don’t need much guidance.

“It’s a legitimate way to grow as a scholar and a researcher and in some ways better than if it was my grant project and I had it all figured out and said do this and do that,” Turner says. The researchers credit Turner with great feedback on their ideas.

Turner was recently informed that a grant proposal has been recommended for funding by the King County Wastewater Treatment Division. They too are interested to learn if fungi mats placed in enough ditches and streams could significantly reduce the bacterial pollution running into Lake Washington and Puget Sound.

The research demonstrates how the University wetlands are being used as a living laboratory with regional impact. It’s also an example of collaboration between faculty, students and the Facilities and Campus Operations staff who maintain the wetlands. And, it gives students real-world experience.

“In terms of grad school acceptance and jobs in the environmental field these kind of research experiences and the connections you make really help you make that next career step – much more than getting good grades or the kinds of courses you take,” Turner said. “Beyond that it’s intellectually stimulating and fun.”

The research was started by Turner and student Phil Van Valkenburg (environmental studies ’15), based on the work of Paul Stamets, a mycologist and author in Olympia who advocates using mushrooms for bioremediation. The particular mushroom used in this bioremediation is the blue oyster. So, the work starts with blue oyster cultivation. The mushrooms that sprout are edible, Turner says, though a steady diet of fecal coliform bacteria doesn’t add to their culinary appeal.

The fungi mats are ready, but the weather is dry. Field testing will start when fall rains increase the water flowing from the wetlands into North Creek. Sampling will show how effectively the mats reduce bacteria. For now, the focus is on the lab experiments to reveal the antimicrobial power of the mushrooms and how best to deploy the inoculated wattles.

The researchers hope their fungi mats could become a best management practice for mitigating bacteria pollution in runoff.

“I think in the long run it’s worth it. What we’re doing will make a difference and will be implemented on a grand scale,” Conejo said.