As a historian, Dr. Dan Berger has a special interest in how freedom and violence have shaped the United States. For more than a decade, the intersection of activism and mass incarceration has been a central theme in both his research and his teaching as a professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

“I’ve long been focused on imprisoned people as political actors and political subjects,” Berger said, “but also with trying to understand how the prison system changes over time and how that relates to the thinking and actions of the people who are held within these prisons.”

The Washington Prison History Project has been at the heart of his research in this area for more than seven years. The project, a multimedia effort to document the history of prisoner activism and policy in the state, has been volunteer-run since its inception in 2017.

In May 2024, Berger received a $1.75 million grant award from the Mellon Foundation’s Imagining Freedom initiative to support the project — he is excited by the new possibilities this transformative funding will bring.

An impactful donation

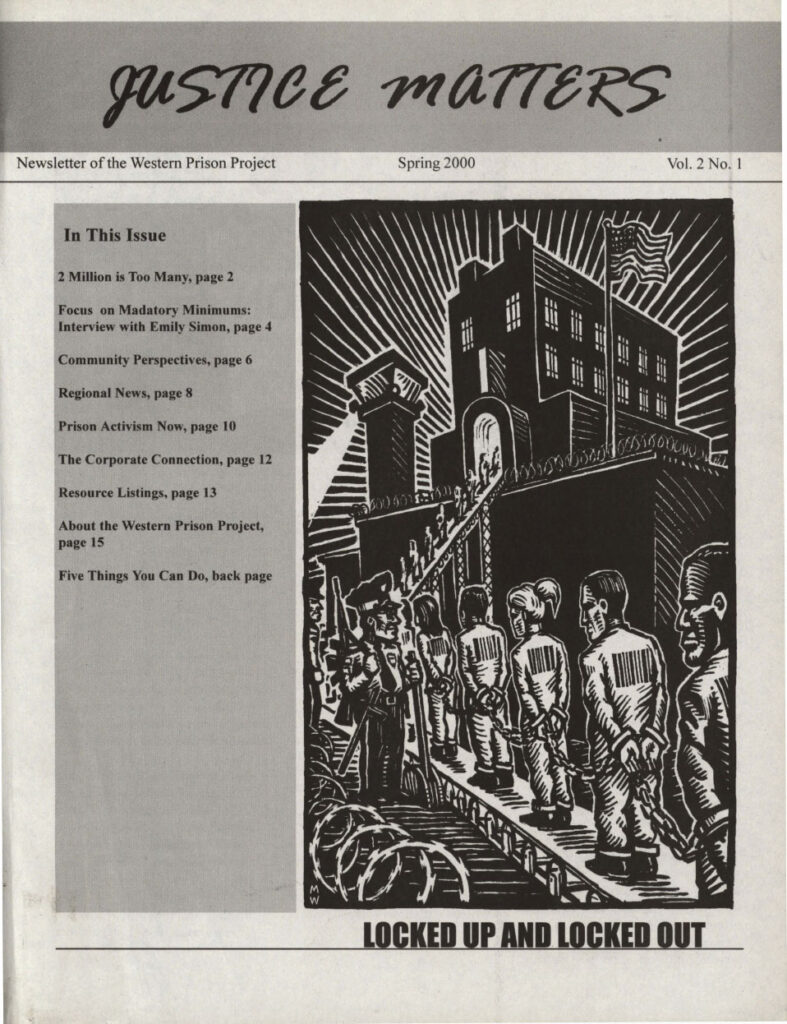

The collection currently houses around 2,000 digital items, including prisoner-produced newspapers, oral histories, testimonials and research on local histories of punishment. It all began with a 2017 donation from a formerly incarcerated man, Ed Mead, who wanted to donate his personal papers from his time as a prisoner and an activist to the University of Washington.

Mead’s passion for advocating for prisoners began long before he himself was a prisoner. In the mid-1970s, he became a founding member of the George Jackson Brigade, a guerrilla group named after a Black Panther member who allegedly attempted escape from San Quentin State Prison in 1971 and was shot and killed.

After his participation in an armed bank robbery in January 1976, Mead was sent to the Washington State Reformatory to serve two consecutive life sentences. While incarcerated, Mead continued his work as a political organizer and activist, advocating for his needs and those of his fellow prisoners through his dissident writings. He remained committed to the cause even after his release in 1993.

By passing his papers on to Berger, Mead’s work could be recorded as a part of history that often gets overlooked, Berger said.

“It was clear almost immediately that these materials weren’t just his personal story but also a window into a collective experience of incarceration in Washington,” Berger said.

Mead’s donation was accepted by the UW Bothell and Cascadia College Campus Library, which processed and archived the materials. “It was a great opportunity to start up both a prison history archive of print and digital materials and a digital scholarship project that could reach the broader public through an open online presence,” said Denise Hattwig, head of digital scholarship and collections for the library.

The project then grew from that initial donation to include other materials from and about incarcerated people in Washington.

A collaborative effort

Through this project, Hattwig said, the library was able to engage in a partnership role to create, preserve and disseminate new knowledge for the public good through an open format.

“Partnerships like this are the future of libraries and one of the ways that the library works with faculty and students to amplify the impact of their research and scholarship,” she said.

As co-curators for the collection, Hattwig and Berger worked together with library staff Mary Schibig, Hannah Mendro and others to digitize, archive and catalogue Mead’s donation. Over time, as more items came in from other formerly incarcerated individuals and other sources, the pair continued to volunteer their free time to the growth and maintenance of the collection, along with Dani Rowland, a campus librarian, and several student volunteers.

The materials are most accessed by fellow researchers and students, but they are also available to the public. On several occasions, Hattwig has heard from family members of some of the formerly incarcerated people featured in the collection, looking to learn more.

“It was really affirming for them to see their history and the history of their loved ones as part of this project,” she said. “It’s a reminder that we don’t collect things just for the sake of collecting things but to create opportunities for real, active and alive connections with what’s happening in the collection that in turn can hopefully have a public impact.”

Over the years, those involved in the project have also collaborated and supported work being done by partners such as Freedom Education Project Puget Sound, an accredited University of Puget Sound program for incarcerated women.

“The project is really exciting because archival work on carceral systems should always be collaborative,” said Tanya Erzen, faculty director for FEPPS. “We’ve been working with people in prison to access the material and conduct research and writing as well as make this accessible to community partners — and the grant will expand this work exponentially.”

The grant award, she noted, will bring even more opportunities for collaboration between FEPPS, UW Bothell and other similar projects across the state.

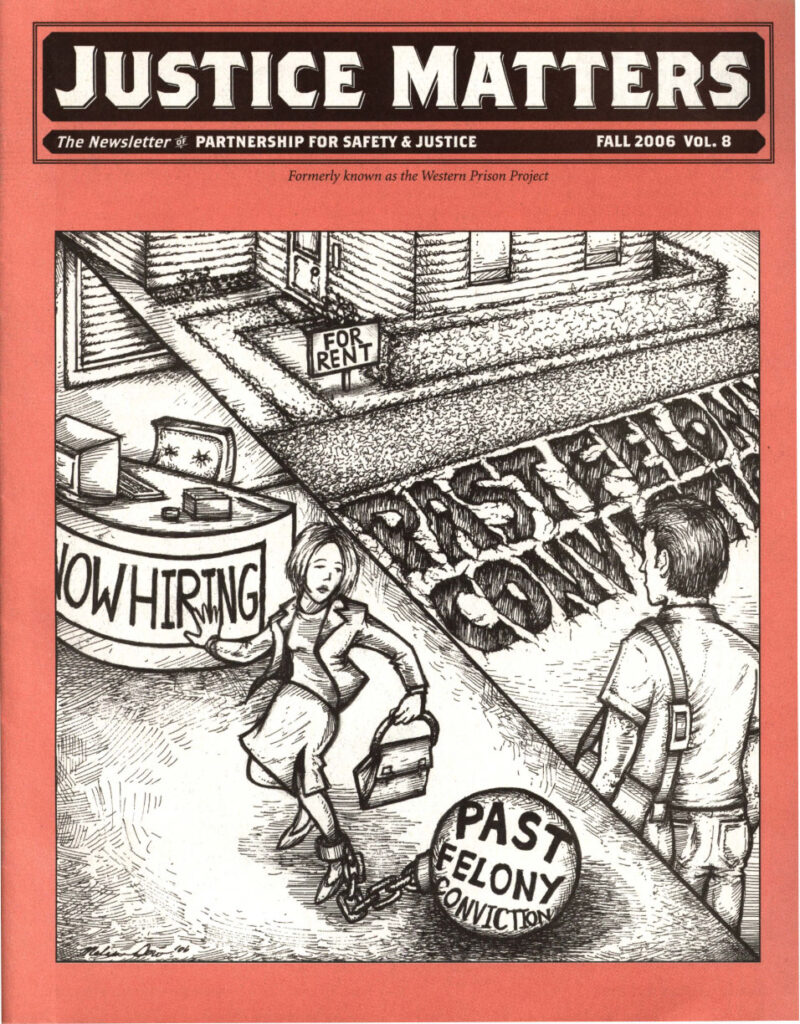

Justice Matters : Newsletter of Partnership for Safety and Justice. Fall 2006, Vol. 8.

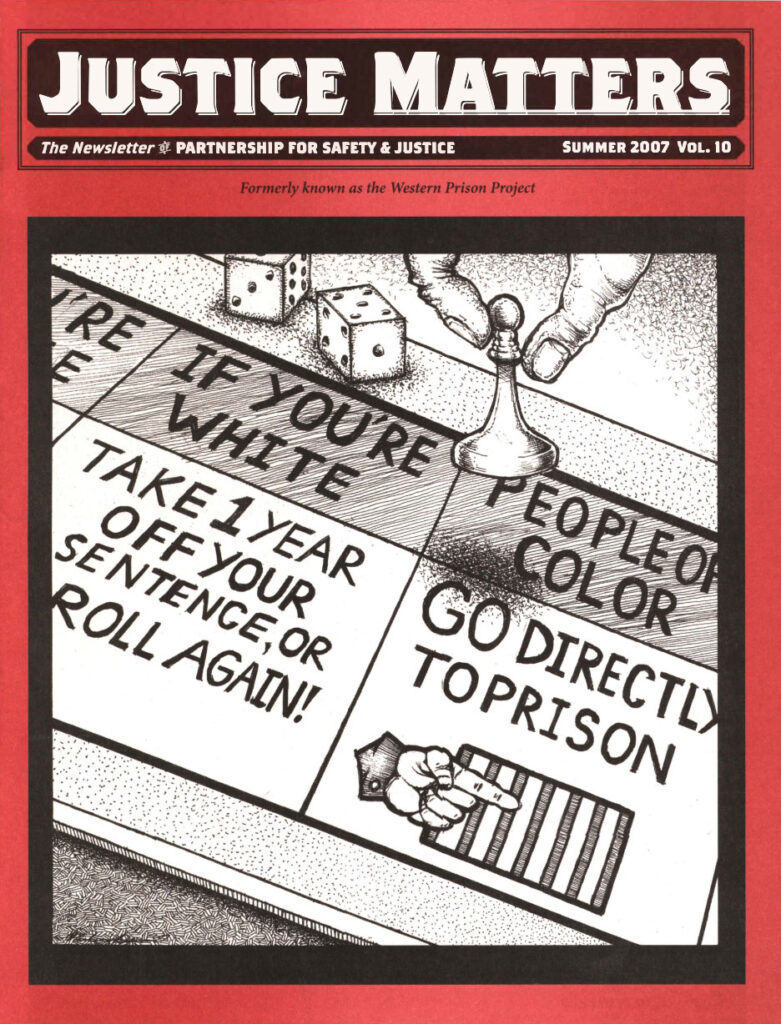

Justice Matters : Newsletter of Partnership for Safety and Justice. Summer 2007, Vol. 10.

“It’s a reminder that we don’t collect things just for the sake of collecting things but to create opportunities for real, active and alive connections that in turn can hopefully have a public impact.”

Denise Hattwig, head of digital scholarship and collections, Campus Library

An engaging experience

One of the items in the collection that people most engage with is The Warden Game, a text-adventure computer game that Mead initially designed and conceived while in prison. Mead was a self-taught computer programmer, learning mostly during his time incarcerated after computers were introduced in some Washington prisons in the mid-1980s.

Among Mead’s donated papers was the programming code he’d developed for the game. Working with then-student Magdalena Donea (Master’s in Cultural Studies, ’18), Berger adapted a new version of the game for a modern audience.

Players are invited to assume the role of a prison warden and are presented with a number of scenarios and possible responses. Berger uses this game in his own courses around the history of mass incarceration, and other educators in both K-12 and higher education have lauded the game as an effective tool for teaching about the power dynamics and struggles of the prison system.

“Being able to approach these subjects through a game is somewhat disarming, particularly as this game was designed by someone who was incarcerated at the time and never knew if he would get out,” Berger said. “Now, more than 30 years later, it’s available as a free teaching tool. That really speaks to the power of archives.

“Because so much of incarceration is shrouded in secrecy, insight into the experiences of people who were incarcerated is all too rare,” he added. “To get both the real historical sense and the speculative sense of what incarceration is like in the form of this game is a really special and beautiful thing.”

Berger hopes to release a second edition of the game using money from the Mellon Foundation award.

A growing collection

Part of Berger’s inspiration for wanting funding to grow the project, he said, were the changes and impacts he began seeing on the prison system during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“As a volunteer project, we had sort of reached the limits of what we could do,” Berger said. “This money gives us the opportunity to do a more thorough, ongoing and detailed investigation into what the pandemic has meant for incarcerated people and the ways that the prison system has changed as a result.”

The three-year grant will support the hiring of three full-time staff positions and give the project team a chance to grow beyond an archival repository to an actively curated collection with opportunities to promote different historical events or lessons from the archive.

Berger also plans to use the funding to establish short-term research fellowships for current and formerly incarcerated people to engage directly with the project.

“Prisons are archives, and incarcerated people themselves are political agents who have been very active in crafting and responding to policy,” Berger said. “They are a vital source for understanding what prison means and what we need instead of prison, and it is through them that we are able to help tell a more expansive story in this larger national saga of mass incarceration.”

This funding, Berger says, will facilitate a growth in both the collection’s focus and its accessibility.

Through the Imagining Freedom initiative, the Mellon Foundation supports artistic, cultural and humanistic work that centers the voices and knowledge of people directly affected by the U.S. criminal legal system.