Mental health is one of the defining public health crises of our time — with devastating effects among young people such as a 40% rise in suicide rates and an 88% rise in emergency room visits for self-harm among Americans ages 10 to 19, according to the National Institutes of Health.

While there is a myriad of mental health issues, anxiety disorders appear to be the most prominent in the United States: Mental Health America reports that 42.5 million Americans suffering from this illness.

Emerald Chuesh (Health Studies ’24) is keenly aware of the severity of the situation and, having struggled with anxiety herself, is passionate about pursuing a career related to adolescent mental health. “Growing up, I felt a constant need for academic validation and had a fear of failure that could be truly suffocating,” she said. “Throughout my life I have tried to get help. As a woman of color suffering from this ‘invisible illness,’ I was often overlooked and not taken seriously.”

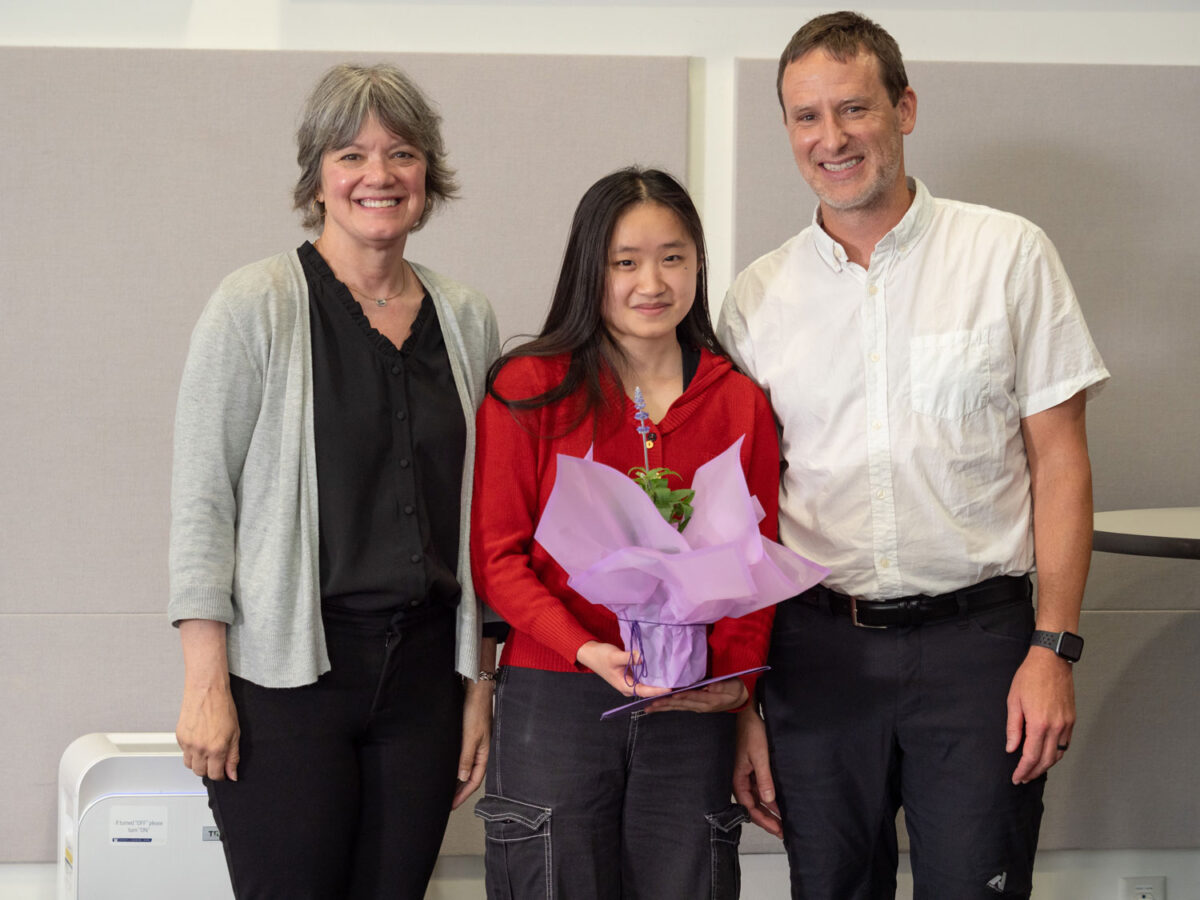

In recognition of all that Chuesh did during her undergraduate career to help others and to prepare for her career, she was named one of the 2024 Husky 100 honorees.

Rising to the occasion

Every year, the University of Washington recognizes 100 undergraduate and graduate students from the Bothell, Seattle and Tacoma campuses who have made the most of their time at the UW — inside and outside the classroom. These Husky 100 students actively connect the dots between what they learn in their studies with what they want to do to make a difference on campus, in their communities and for the world.

Chuesh, who minored in Biology and in Neuroscience, is one of six honorees from UW Bothell.

She also participated in a research study, worked as a day camp unit leader for children with disabilities, volunteered at the UW Bothell’s Collaboratory and held a position as an undergraduate research assistant for the Short Mindfulness Activity to Reduce Test Stress (or SMARTS) project administered by Dr. Bryan White and Dr. Linda Eaton.

“Emerald is a perfectionist, and when I first met her, I saw the struggles she had with anxiety,” said White. “However, in the year and a half I worked with her, I have witnessed a grand transformation. She has pushed herself outside of her comfort zone so many times and continues to rise to the occasion.”

Testing test anxiety

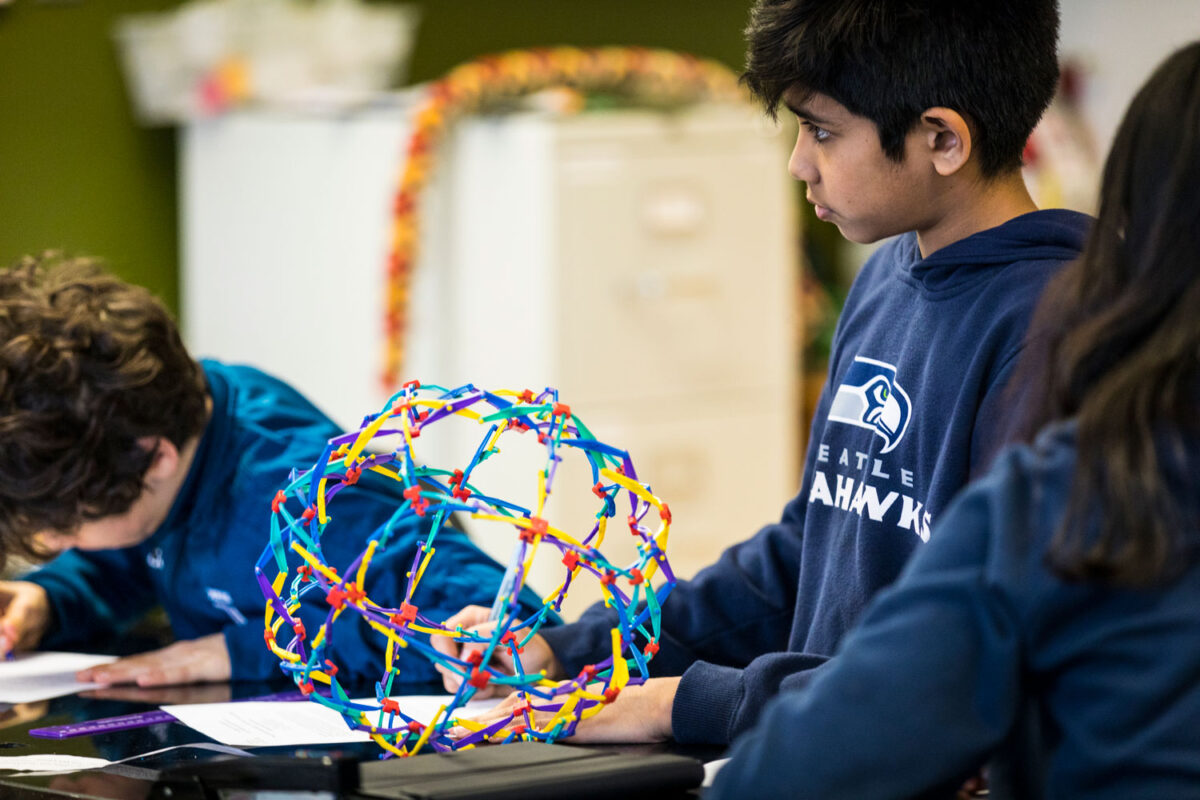

Chuesh got her first experience doing research into the mental health of adolescents and college students through the SMARTS project.

Eaton, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing & Health Studies, and White, a teaching professor in the School of STEM, wanted to find out if mindfulness could work in reducing test anxiety in students. More than 50 students applied to be part of the project, but only three were hired — and Chuesh was one of them.

“This was my first ‘I can make a difference’ moment,” she said. “I could finally be a part of something impactful.”

She and her fellow researchers set out to design a mindfulness intervention audio recording that students could listen to before exams in the hopes of lowering their heart rates, improving their physiological health and making them feel calmer — and therefore able to perform better on their tests.

“This was my first ‘I can make a difference’ moment. I could finally be a part of something impactful.”

Emerald Chuesh, Health Studies ’24

Revealing results

The final recording was seven minutes long and incorporated pieces from different mindfulness practices including a breathing exercise, a body scan and a segment on positive affirmations.

Based on data collected from 29 students, the results revealed that a short mindfulness activity did reduce increases in heart rates during exams. Also noteworthy was the result that 56% of participants said they would continue to use the recording before a future exam.

“The experience was inspirational as I got to work with real people and learn their names, their experiences with test anxiety and why this study was as important to them as it was to me,” Chuesh said. “It also showed me that the applications of non-pharmacological treatments and non-Western medicine, such as our mindfulness intervention, can hold great significance in public health.”

She also explained that many cultures have deep histories with traditional medicine from natural remedies. “I’ve witnessed how individuals will shy away from unfamiliar Western treatments, such as synthesized pills, despite their high success rates,” she said.

“Understanding and working with underrepresented populations is a key aspect of public health. Given I am considering becoming a health care worker, I need to try my best to understand the perspectives and viewpoints of multiple marginalized groups.”

Difficult and rewarding

Chuesh had been exploring the idea of becoming a doctor when she decided to work as a day camp unit leader for children with disabilities so that she would get experience working with a marginalized community.

She supervised children in recreational activities and managed their behaviors within the group all the while remaining flexible to individual needs and requirements. “Despite the training, this was one of the most difficult and challenging jobs of my life,” she said. “But it was also the most rewarding experience I’ve ever had.”

The children were aged two to 12, and their disabilities ranged from mental to physical. When describing them, Chuesh said, “They’re genuinely some of the coolest people I’ve ever met. They’re athletic, intelligent and creative.”

White, who often met with Chuesh after she had worked at the summer camp all day, recalled that “she would be exhausted and have scratches up and down her arms from the various activities, yet she would look forward to the next day. She found ways to relate to her campers and comfort them, perhaps using her own experiences in taming her anxious brain to make connections and help them through difficult moments.”

Exploring the options

After the camp experience, Chuesh branched out into more technical settings — volunteering at the Collaboratory and taking a position as a biology lab assistant.

It was working in these new environments that then sparked Chuesh’s interest in potentially becoming a neuroscientist.

“A lot of the time mental health is seen as invisible. I would like to solidify that something is happening in your brain,” she said. “I want to scientifically prove that it’s not just ‘all in your head’ and show the actual mechanisms and metabolic pathways that are influencing your mental health.”

While she doesn’t know for certain if neuroscience will be her path, she is determined to work in mental health in some capacity. “I want to help people who are struggling with their mental health — whether as a researcher, doctor or maybe even something else entirely,” she said.

“I want to be the advocate for others that I never had.”