The phrase “model minority” was first used in reference to Asian Americans during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Some pointed to Asian Americans as being successful and well-adjusted — despite their own recent history of racial oppression which included the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The phrase was meant to pose a challenge to African American activists: “Why can’t you be more like them?” And from its earliest usage, the myth of the model minority has driven a wedge among racially marginalized groups and has put undue pressure on Asian Americans, said Dr. Jaki Yi, assistant professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

“Asian Americans are lauded for being academically oriented, hardworking, high achievers because of the values supposedly inherent in their culture,” she said. “These are all things that are positive on the surface but have really harmful mental health implications for Asian Americans who are faced with it.”

Given that Asian Americans are often characterized as quiet and unproblematic, she added, “the group is also frequently stereotyped as lacking an interest in activism.”

Finding meaning

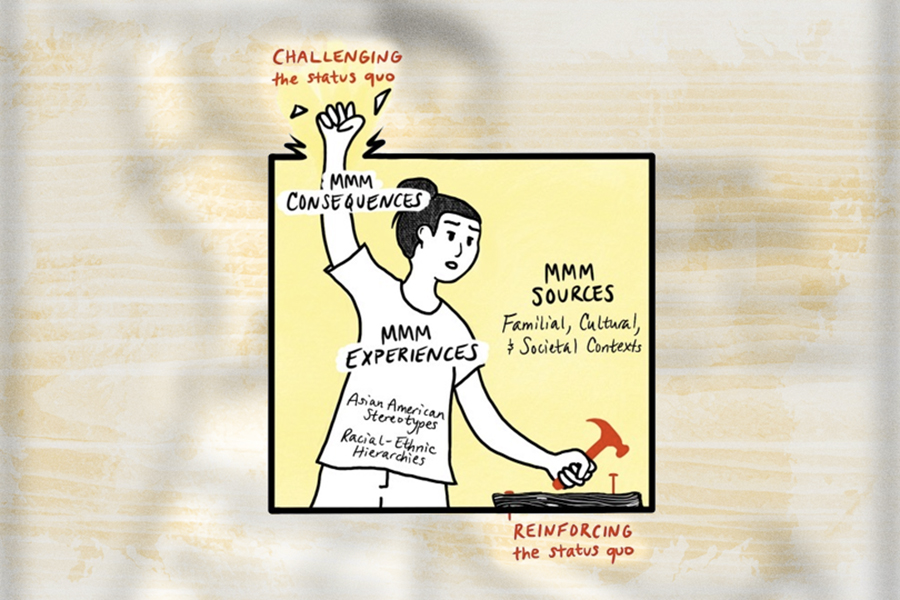

In her recently published study, “Reinforcing or Challenging the Status Quo: A Grounded Theory of How the Model Minority Myth Shapes Asian American Activism,” Yi examines these themes and investigates the link between the myth and activism among Asian American students.

While completing her undergraduate degree in Applied Psychology at New York University, Yi first became interested in the research aspects of the field while exploring racial and gender disparities in New York’s juvenile justice system.

“Learning about how research can be done in really innovative, community-based ways that aim to help people from marginalized backgrounds really inspired me to continue with that work,” she said. “I want to be part of helping to understand what it means to be Asian American and to contribute to ethnic minority psychological research and practice.”

Together with Dr. Nathan Todd, Yi began work on her doctoral dissertation while studying Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She interviewed 25 Asian American college students about how they viewed the model minority myth and how they viewed activism.

“College is such a pivotal time when students, for the first time, might be experiencing different ideologies, interacting with diverse communities and learning about systemic racism in a lot of ways,” Yi said. “I was curious how they understood the model minority myth and if it had affected whether or not they engaged in social justice activism.”

Asian Americans are often stereotyped to be apolitical and perceived as wanting to protect their model minority status, she noted, despite their having a rich history of involvement in social justice movements.

I want to be part of helping to understand what it means to be Asian American and to contribute to ethnic minority psychology, research and practice.

Dr. Jaki Yi, School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences

Listening to students

In her interviews, Yi said many students noted feeling anxiety or pressure from the high standards imposed on them as a result of the model minority myth.

One student said, “People think I’m supposed to be super good at certain things, when in reality I’m just kind of average … that can take a really big toll on you, because you think, ‘I’m not good enough. I’m not doing this right. I’m letting myself down. I’m letting others down.’”

Yi also discussed with students the various sources that create and perpetuate the myth. At a macro level, this includes cultural and societal contexts. These ideals can also be embedded at a micro level in family dynamics, she said, noting that participants were also asked about their parents’ beliefs around the model minority myth and activism.

A participant noted that their parents “think that Black people get hated on a lot because they stand up for themselves. And they think that Asian people are doing it right because they’re not standing up for themselves, and that’s why we don’t get hated on as much.”

These interviews were all conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which spurred a spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans. So Yi did several follow up interviews in 2020 and 2021 to see how understanding of the myth might have changed.

“A lot of Asian people I know were very active in Black Lives Matter, and I’ve also seen a lot of people involved in that movement who are very outspoken for supporting Asian Americans during this time right now,” said one student. “Because of the recent hate crimes, Asian Americans really now understand the struggles that Black Americans go through. It has made us resonate with other minority groups even more, because now we really feel what they have felt.”

Rejecting myths

While many of the students interviewed expressed feeling boxed in by the stereotype and unable to engage in activism as they might otherwise want to, Yi discovered that others exhibited a strong rejection of the myth and sought to challenge the status quo.

“People are shocked to see me as an activist. Being an activist, you have to be assertive, you have to stand for your values,” one participant said. “As an Asian American, I almost have that spite of disproving [the model minority myth], which makes me more assertive. The model minority has kind of empowered me in that way, by making me try to disprove it.”

Responses also varied among different Asian ethnic groups. Students from South Asian and East Asian backgrounds noted that they’re often not seen as Asian Americans. Research participants in these groups reported an added layer of racism related to their religious identities. For South Asian and Muslim-identified students in particular, Yi said the racial stereotype of being perceived as a “terrorist” was in harsh juxtaposition to the model minority myth.

First-generation Asian Americans were also more likely to express feeling pressure from family not to engage in activism, the study found. Because of the challenges their parents faced as immigrants, the next generation was encouraged to not “rock the boat.”

But according to Yi, “a lot of the students — the second-generation Asian Americans I interviewed, as well as the students I work with now at UW Bothell — are wanting to push against those narratives while also maintaining respect of their parents and culture.”

Exploring new perspectives

Because the study looked specifically at a campus community in the Midwest, Yi is now curious to find out how results might differ in the Seattle area.

“More research and practice need to be done on how we can get Asian American youth to reject the model minority myth and have opportunities to learn about their histories and how to engage in social justice,” Yi said. She believes community interventions, as well as mental health and clinical interventions, could be a tool to help empower Asian American people to challenge the myth.

Currently in her first year of teaching at UW Bothell, Yi said she looks forward to continuing her research and engaging a team of undergraduate research assistants.

“The School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences at UW Bothell has such a strong social justice orientation, and the diverse, multi-cultural campus has a lot of first-generation students,” Yi said. “That’s something that really drew me to this campus: the ability to work with this student population and for them to have the opportunity to see themselves in their own work.

“I’m so excited to continue this research on this campus.”