Hip-hop is celebrating its 50-year anniversary in August, and people across the country are reflecting on the impacts the music genre has had over the past five decades. For Dr. Georgia Roberts, however, hip-hop is always at the forefront of her mind — anniversary or not. Roberts, who is a lecturer at the University of Washington Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, has been listening to and studying hip-hop music since early childhood.

“In some ways, hip-hop provided an alternative history to that written about in textbooks,” she said. “Growing up, I listened to artists such as Tupac Shakur who rapped about the Black Panthers and Malcom X. We weren’t learning about the Black Panther Party in school, and in the days before the internet, I would go to the library and check out books because of Tupac.”

As a first-generation college student at University of California, Berkeley in the late 1990s, Roberts remembers writing hip-hop lyrics in the margins of “Allegory of the Cave” by Plato and “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison. “For me, the ideas didn’t come from books and then get represented in songs,” she said. “It was the other way around: They came from songs, and then I found correlations in books.”

Now, Roberts has been teaching courses on the history of hip-hop for more than 20 years.

Not surprisingly, the first course she developed as a doctoral student in English was on the books that influenced Tupac. Her classes at UW Bothell emulate the very thing she did as an adolescent, although on a much more intentional level — putting rap lyrics into conversation with historical texts and finding connections between music, theory and political movements.

A block party in the Bronx

At the start of each hip-hop course, Roberts gives students an overview of the genre, beginning with its origin story. “Hip-hop was born in the summer of 1973 at a back-to-school party in the Bronx in New York City,” she said. “By using two turntables and a mixer to fade between two copies of the same record, DJ Kool Herc extended the breakdown or ‘break’ of a song. This is one of the key elements in hip-hop music.”

It wasn’t until six years later that the first hip-hop song was recorded and released, introducing the genre to a wider audience. It quickly gained popularity in mainstream media, and by the 1980s the genre expanded beyond New York. It could be heard on the radio and in clubs in various major cities and by the early 1990s had established itself as a mainstay in popular music.

“My class is focused on contextualizing some of the thinking that influenced early hip-hop,” Roberts said. “From a lyrical perspective, rap demonstrated a nuance in thinking about race, class and gender in the post-Civil Rights moment of the United States. But it also showed how people were beginning to rethink politics as the ultimate horizon for meaningful social change.”

Roberts said albums such as Tupac’s first release, 2Pacalypse Now (1991), give voice to the concerns that people had about issues such as the war on drugs and its relationship to over-incarceration. “‘Trapped,’” was one of Tupac’s first solo songs and highlighted how racial profiling and over-policing in many inner-city neighborhoods was affecting young Black men,” she said.

A new conversation

The class unit on Tupac’s work includes selections from his mother Afeni Shakur’s biography, “Evolution of a Revolutionary” by Jasmine Guy, and from an article from Gwendolyn Pough, titled “Seeds and Legacies,” which explores the relationship between the Black Power movement and Tupac’s work. “Pough argues that Tupac became the physical embodiment for the link between the Black Power movement and hip-hop culture, as both are grassroots movements started by young Black people and both worked to disrupt the status quo on varying levels,” Roberts said.

She asks her students to think about the discourse that was taking place at the time and how hip-hop didn’t just repeat but rather reinvented conversations about over-policing and police brutality.

“Hip-hop is about having a perspective, about speaking from your social location and trying to address things that matter — not to speak for other people but to listen and use your voice as part of larger democratic practice,” Roberts said. “I want to encourage students to think about how artists position their arguments and how they support their point-of-view within the lyrics.

“But at the same time, it’s important to remember that rap is not always a direct reflection of reality,” she said. “It’s an art form, and like other modes of poetry, it includes many genres — think allegory, satire, parody and elegy.”

Music and movements

For one of their class assignments, students research where they live in Seattle and use the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project website to learn about the history of the racial covenants in their neighborhoods — where people could and could not live according to race.

“Early on in the course, we look at how the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway in New York in the 1950s shaped the environment of the South Bronx,” Roberts said. “This assignment is an effort to better understand the history of Seattle, and more specifically, the role that racialized policies played in shaping Seattle’s neighborhoods.”

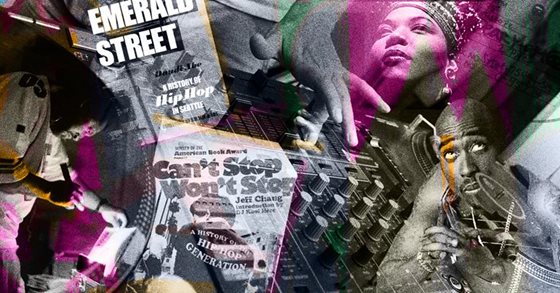

The class also listens to songs from local artists such as Draze, who writes about the effects of gentrification in Seattle’s Central District in his song “The Hood Ain’t the Same.” Select readings from Daudi Abe’s recent book “Emerald Street” show how Seattle hip-hop artists and organizers have addressed concerns over community issues for a long time.

New perspectives matter

Diego Cuevas, a senior studying finance in the School of Business, has lived in South Everett almost his entire life and said learning about the city’s history was eye-opening. “Hip-hop was created by people who lived in the ghettos because of racial segregation,” Cuevas said. “It’s hard to imagine that happening in the neighborhood I live in now, but it did.

“People of all different races live here, but that was not always the case. I learned that older neighborhoods in the city of Everett were racially segregated. There was a covenant that stated that ‘no race or nationality other than the white or Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building on any lot,’” he said. “Hearing about the impact of that in the songs we studied and imagining it in the streets I walk in everyday made the class material that much more real and meaningful.”

It wasn’t just the material that impacted Cuevas; it was Roberts, too.

“I actually enrolled in the class in part because Dr. Roberts was teaching it,” Cuevas said. “Her passion makes the subject that much more interesting, and I appreciate that she doesn’t lecture —she invites conversation.

“She makes me feel like my opinions and perspectives matter, and takes them seriously, always asking me what I think and encouraging me to contribute.”

A momentous milestone

While hip-hop is celebrating its 50th anniversary in August, Roberts will be simultaneously celebrating her 20th anniversary of teaching about the genre, and her experiences lead her to think deeply about what this 50-year milestone represents.

“The museums and other institutional celebrations of the 50th anniversary of hip-hop are important because they mark a moment of reflection in our larger, collective understanding about the history and trajectory of hip-hop,” Roberts said. “I’m interested how moments of historical framing can also be opportunities to look back and learn new things.”

Robert said it’s important to assess the progress of social issues that many artists continue to address through the medium of hip-hop, both in the U.S. and globally.

“It may have been the case 50 years ago that rap spoke truth to power at a crucial time in history, educating a generation of young people in the process, but where are we now? And where do we want to be 50 years from now?” she asked.

Two ideas in tension

What Roberts hopes people take away from the anniversary is similar to what she hopes students take away from the class.

“There are important lessons hip-hop has inherited from the Black radical tradition, especially around speaking truth to power, organizing and creating social networks of care,” Roberts said. “I think part of what makes hip-hop really rich is that, yes, it’s protest music to an extent, but it’s not just that.

“Hip-hop asks us listen to other people’s perspectives and sit with contradiction, confusion and sadness, knowing that many of the most pressing social questions cannot be immediately resolved,” she said. “Hip-hop is about learning to be with the contradictions that we live in, all the things that we’re trying to change or wish could somehow be different.”

Both personally and as a teacher, Roberts says this tension is important to examine.

“The art that I’m drawn to encourages us to be realistic about the inconsistencies and conflicts as they exist right now, but still find ways to study and be together,” she said. “To hold these two things in constant but productive tension with one another might just be one of the most important things a person can learn.”