The Hanford Nuclear Reservation, located in southeast Washington state, is the most contaminated nuclear site in the Western Hemisphere.

During World War II and the Cold War, the federal government used the site to make plutonium for nuclear weapons. Workers at Hanford produced the plutonium so quickly that they started ‘disposing’ hazardous waste directly into the air, the soil, the Columbia River and unlined trenches. Over the years, this totaled to more than 450 billion gallons of radioactive and chemical waste — the equivalent of more than 680,000 Olympic size swimming pools.

While all this happened decades ago, the radioactive and chemical waste created during this time is still being dealt with today.

“Plutonium has a half-life of 24,000 years, which makes it an inherently intergenerational problem,” said Dr. Shannon Cram, assistant professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences at the University of Washington Bothell. “Cleanup doesn’t make Hanford’s waste disappear. Much of it will be there forever, in human time scales.”

To help raise awareness of the site and to advocate for its safe cleanup, Cram recently called upon the creative powers of UW Bothell students.

Building on her history with Hanford

Cram is a longtime member of Hanford Challenge, an organization dedicated to cleaning up the site as well as worker health and safety. She began volunteering with the organization in 2009 while conducting dissertation research in graduate school.

“My grandfather built roads at Hanford during the Cold War, and my family is from the area,” she said, “so I have my own intergenerational relationship with the site.”

She currently represents the UW on the Hanford Advisory Board, a multi-stakeholder body that provides policy advice to the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Washington State Department of Ecology. One of Cram’s core interests serving on the HAB is public involvement — finding creative ways for individuals and communities to engage in meaningful conversations about the cleanup process.

Recently, she collaborated with Hanford Challenge to facilitate the organization’s Hot Poetry contest at UW Bothell, which invites students to write poems about the legacy of nuclear weapon waste. Cleanup is an interdisciplinary challenge, and the poetry contest has drawn students from across the University’s schools, including majors in Educational Studies, Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, Nursing & Health Studies and STEM.

“Because the Hanford Site will affect generations to come, one of Hanford Challenge’s primary goals is to involve young people in cleanup efforts,” Cram said. “This poetry contest helps to spread awareness and is open to any college or university student 18 years or older in Washington state.”

A place for the things we can’t solve

Dr. Sunita Iyer, associate teaching professor in the School of Nursing & Health Studies, required students in one of her health policy classes to submit poems to the Hanford Challenge.

“I love weaving art and writing into my courses,” Iyer said, “I write poetry myself and think of it as a place for the things we can’t necessarily solve and as an art form that makes intimidating topics accessible.”

The Hanford Site is certainly an intimidating topic, noted Cram, and members of the public often don’t know where or how to engage. “One of the great things about using poetry to think about cleanup is that it doesn’t require students to have a vast technical or policy background,” she said. “Poetry allows students to participate in a conversation about Hanford in a way that feels meaningful and accessible.

“We all have something to say about intergenerational equity or wanting a clean environment or safety for workers — those are things we can all speak to, regardless of our area of study.”

The students in Iyer’s course spent a large part of the quarter learning about Hanford, having Cram as a guest speaker and using resources from the Hanford Challenge’s website. Iyer also led them through a study of poetry, viewing it as both activism and a healthy form of human expression. “Scientific health research is often hard to digest,” she explained, “and research suggests that poetry can help.”

When poetry and science come together

As part of the curriculum, students watched a TEDx Talk by Dr. Michelle Redman-MacLaren, Iyer said, “and she suggests that ‘using arts in research can be a new way of understanding health challenges and can also help improve health outcomes. Poetry can generate new knowledge, represent findings and influence the use of research for positive change.’”

In addition to studying poetry, the students wrote poems of their own. Two class sessions were spent creating group poems that responded to discussions on the health care system, inequities and disparities in health care and policy.

“I had students share words that represented how it felt to be voiceless, frustrated and yet saddled with the responsibility of the health care system — and use these words and phrases to create this incredible poem,” Iyer said. “I was so proud of them when they finished. They created a poem that has feeling and meaning, that moves people to think about health care inequities.

“They didn’t just tell people. They showed them what it feels like, and that’s very different.”

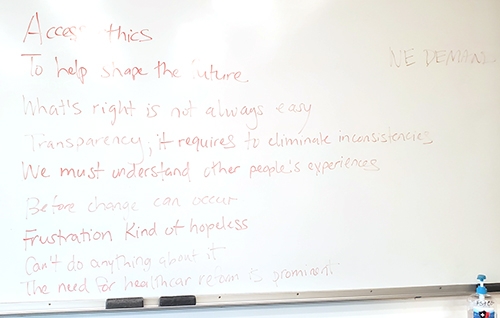

Here is the poem the class created in an informal, unrefined, free association exercise:

UntitledAccess ethics

To help shape the future

What’s right is not always easy

Transparency, it requires to eliminate inconsistencies

We must understand other people’s experiences

Before change can occur

Frustration, kind of hopeless

Can’t do anything about it

The need for health care reform is prominent

WE DEMAND

Looking hard into the mirror

Iyer’s final assignment for students was to write an individual poem that related to nuclear weapon waste.

For senior Bethlehem Obssie, this was her first time both studying the Hanford Site and writing a poem. “Learning about Hanford was incredibly shocking,” she said. “I have lived in Washington my whole life, and I never, not once, heard about this nuclear waste site.”

The site also sparked a lot of self-reflection for Obssie. “I couldn’t believe this was something I didn’t know about,” she said. “It made me want to become more aware of the environment and also my own, sometimes damaging, contributions.”

She decided to write her poem from her own viewpoint and from that of the United States of America. “I wanted to speak for me and my country, so everything was written as You and I,” she explained. “Everyone in the United States is guilty of polluting the environment to some extent, myself included. We may not be developing nuclear bombs, but we all leave a carbon footprint. It’s easy to point fingers, but what’s hard is acknowledging your own faults.

“I hope that my poem encourages people to take some accountability and also inspires them to reflect and think about how they can be better moving forward,” she said. “I grew up Christian so I made it a sinner’s prayer. We — me and my country — have done so much harm that there is no atonement. Likely for the rest of humanity, the contamination at Hanford will continue.”

A sinner’s hymn

Are You and I desensitized?

They recall.

Stumbling upon a land, We crowned Ourselves good.

But, You and I marginalized and terrorized.

We built bombs.

We caused irrevocable harm.

We contaminated willfully.

Destroyed their land.

The River narrates Our story.

The soil Our DNA.

We can’t run from who We are,

Sinners.

Who displaced and created endless waste,

For Us to triumph? And remain good?

It will take thousands of years,

To atone for what We did.

Even then,

We never will.

The land remembers Us.

Generations can pass.

They’ll never forget what We did.

Are we still desensitized?

From class conversations to imagining radical acts

Iyer’s class submitted 25 poems to the Hot Poetry contest, and both Iyer and Cram are pleased with the deep conversations the project inspired.

“I am so happy to see young people engage with cleanup in this moving and powerful way,” Cram said. “Most people, especially on the west side of the state, have never heard of Hanford.

“These poems can change that in a small way. Just talking about Hanford — telling others that the site exists —is a radical and important act.”