Growing up in the United States, Justin Totaan felt like he was two halves of a person that didn’t quite make a whole. His parents emigrated from the Philippines, and the starkness of cultures between his home and public life made it challenging for him to acclimate.

“When I was at school or with friends, I always felt too foreign, but whenever I was at home, I felt too American,” said Totaan, a graduate student at the University of Washington Bothell. “I have never felt as though I truly belonged anywhere.”

This feeling of “otherness” is one that many immigrants and their descendants experience. Through a new program called Southeast Asian Pasts and Futures, however, students at UW Bothell can create a sense of connection and belonging they have been yearning for, some their entire lives.

Said Totaan, “In elementary and high school, I was always teased about my culture. This was the first time I got to be proud of my heritage in a classroom.”

Celebrating their strengths

SEAPF spans three quarters and is taught by Dr. Raissa DeSmet, associate teaching professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, and Nhi Tran, academic adviser and affiliate faculty. The program brings together Asian Pacific Islander Desi Americans students to celebrate their cultural strength and resilience.

When developing the program, DeSmet drew inspiration from Research Family, a program established by Dr. Holly Barker, teaching professor in the Department of Anthropology at UW in Seattle. Research Family uses the Pacific Islander cultural collections at the Burke Museum to provide research opportunities for students who are traditionally underrepresented in this kind of work.

After hearing about the museum program in 2015, DeSmet began dreaming of starting a similar program for Southeast Asian students at UW Bothell.

“Southeast Asian students can feel minoritized within Asian and Pacific Islander formations. We have particular migration histories, material realities and experiences of racialization and racism,” she said. “When I found out that the Southeast Asian cultural belongings in the Burke Museum were seldom accessed by community members, I saw an opportunity for healing.”

Bringing past into present

After partnering with the Burke for several years to create various museum and culture focused classes, DeSmet’s larger programmatic dreams finally came to fruition in autumn 2021 with funding from the University’s Southeast Asia Center in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

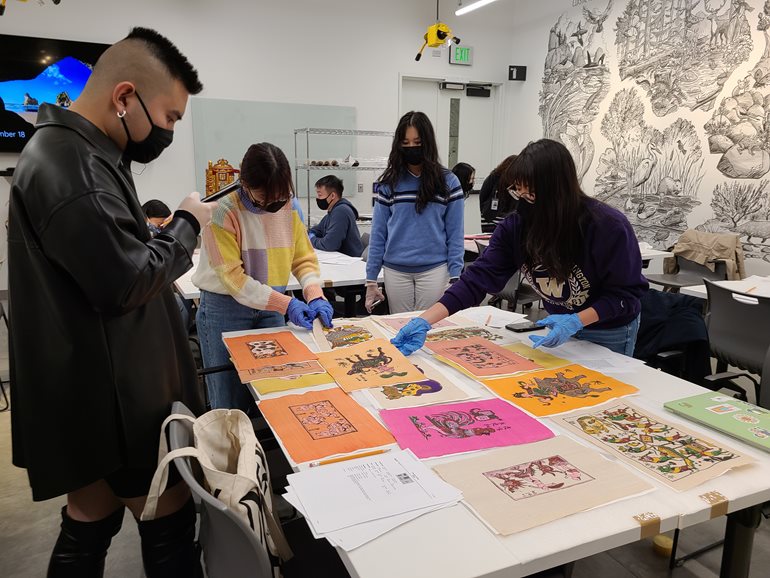

With the support of UW faculty and Burke Museum staff, students in UW Bothell’s inaugural SEAPF program designed their own research projects, working directly with objects in the Southeast Asian collections and building relationships with APIDA knowledge holders in the Puget Sound. Each quarter, they participated in critical conversations and community-building activities while exploring the field of museum studies and practicing indigenous research methods.

“Through SEAPF, we connect Southeast Asian students with these pieces that are sitting on museum shelves, not visited, not held, not spoken or sung to,” DeSmet said. “By facilitating interactions between students and objects that are representative of their culture, we begin cultural renewal work that is object centered.”

Cultural renewal is a process, DeSmet said, of “finding strength in our identities and traditions, our resistance to oppressive forces, and our resilience and creativity as communities.”

One way students in the program did this work was by writing about an object that represents who they are and where they came from. Two such objects are chop sticks and a mortar and pestle.

Picked apart with chopsticks

Henry Nguyen, a senior majoring in Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies and in Media & Communication Studies, said that he remembers as a child being scolded for the way he used chopsticks.

“My grandma always closely scrutinized the movement of my chopsticks, waited for me to drop something and humiliated my table manners,” he said. “Even when I managed to pick up the food without dropping anything or making a noise, she still criticized me for having the pinky finger pointing out while holding the chopsticks.”

Nguyen moved to the United States from Vietnam in his late childhood. Despite moving halfway across the globe, the memories of those nights at the table stayed with him, and whenever he finds himself in an Asian restaurant, those memories come swarming back.

“I see people doing little dances with their chopsticks, dropping them multiple times or pointing their chopsticks at each other,” he said. “It drives me crazy seeing how people disrespectfully handle their chopsticks — and it drives me crazy seeing how unfair it was for my grandma to scrutinize the way I used my chopsticks.”

Creating a story of family

During his time at the Burke Museum, Nguyen learned to treat objects with love and care. He vividly remembers walking into the collections room for the first time and learning about how objects end up at a museum. “Some objects lost their historical context, some carry violence, some experience diaspora — finding a ‘home’ in a faraway place,” he said.

“When I decided to write my piece on chopsticks, I knew to handle the object with care, protection and thoughtfulness. A pair of chopsticks is not simply an inanimate object. Instead, it holds a part of my lived experience. It connects me with my grandma,” he said.

Before Nguyen wrote his reflection titled Chopsticks — More Than Just a Utensil, he and his grandmother were not on good terms. But the more he researched the significance of chopsticks, the more empathy he had for her.

“I learned about the cultural beauty of chopsticks use. Appropriate chopsticks use means refined table manners, it means treasuring the food,” he said. “It also means treating our ancestors with respect.”

One item, thousands of memories

Molly Kappes, a senior in the School of STEM, also has childhood memories tied to culturally significant objects. One of her is a mortar and pestle.

“Some of my earliest memories are of my mom cooking for me and my siblings in the kitchen. Each meal was made from the heart, and the amount of love she put in always hid the labor and skill required of traditional Khmer cooking,” Kappes said. “We had to eat everything on our plates, no exceptions. ‘Every bite is hard-won,’ she would say.”

Throughout Kappes’ childhood, she saw her mother meticulously smash, grind and pound various ingredients in this mortar, and it became synonymous in her mind with family dinners and full stomachs. “Its worn appearance could tell anyone it was well used, and to me it radiated love,” she said. “I didn’t know until I was older what significance this mortar and pestle held for my mom and our family history.”

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge won the Cambodian Civil War and took control of Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. “Led by Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge began to commit countless atrocities that over approximately three years, led to the loss of more than a quarter of the country’s population,” Kappes said. “My mom’s family first experienced the hardships of war after the disappearance of my great-grandpa, who was Chinese.

“My grandpa, his son, tried using his government connections to get my great grandpa back. But shortly after, my grandma was held at gunpoint under suspicion of being Vietnamese, and they knew it was too dangerous to stay.”

Extending past tragedy

That was the start of a seven-year journey of uncertainty and insecurity. Besides the few personal items each child could carry, her family took only their gold and jewelry, some woven mats, a silver spoon, and the mortar and pestle her mom still uses.

“By the time they landed in Ohio as refugees, the mortar and pestle was the only object that remained with my mom’s family,” Kappes said. “This mortar and pestle saw the hardship of war. It remembers the heartbreak of separation, not knowing when or if they would see each other again, and the unimaginable loss of family.”

She said that despite the violence these objects have seen through their lifetime, it isn’t a war artifact to be observed. It’s a tool to be used, still capable of creating joy and fond memories. “Learning about the mortar and pestle’s history didn’t taint the positivity I had formed around it — it extended it,” Kappes said.

“Working with cultural belongings at the Burke Museum helped me develop a sensitivity to individual histories that was crucial when looking at something from my own history. It’s easy to see a museum object as something transformed,” she said, “but many of these items were just plucked from their homes and put on display.

“There’s something powerful about combining personal connection with this kind of research. Because of it, I feel a much deeper connection to my family story.”

Lasting cultural connections

Nguyen and Kappe’s reflections about these items, along with those of their classmates, will be featured in a zine they are publishing this summer.

Tran said the students exceeded her expectations. Nguyen’s work in the program, for example, helped earn him a internship at the Massage Parlor Outreach Project, an organization that advocates and supports migrant Asian massage workers in Seattle.

“The students all blew me away in terms of their energy, their support and their care for one another and dedication to their work,” Tran said. “These students didn’t know each other when they first started this class, now they are best friends. The friendship, connection and community — that is forever.”

For those interested in participating in the 2023 program, visit the application website.