Over the last century, the entirety of the world has seemingly shrunk. From radios and television to personal computers and the ever-evolving cellphone, it now appears as though the whole world can fit in the palm of a person’s hand. Afterall, with social media applications, these phones are no longer just a device used to make a phone call. They have become a bridge to much larger conversations.

But what topics get spoken about on these platforms, and who gets heard?

Those are the kinds of questions that University of Washington Bothell students in Dr. Min Tang’s class, Critical Media Literacy, strive to answer. Tang, assistant teaching professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, designed the class to encourage students to think about how they can use media to empower themselves and disenfranchised communities. “With so much time being spent on social media, it’s increasingly important for students to be thinking about how power structures in a society shape the media systems and processes,” Tang said.

Wanting to extend this dialogue beyond her immediate classroom, Tang partnered with the Northshore School District. Through her class, students propose and create workshops that highlight identity politics in media, focusing on how systems of oppression operate.

“With media becoming more prominent in our world, I want my students to be able to analyze media messages as well as create, reflect and take action. I want them to use the power of information and communication technologies to make a difference in the world,” Tang said. “I felt doing a workshop would be a great way to participate in something influential within the community setting.”

Student to teacher

Tang has been teaching this course for five years, but winter 2022 was the first time students presented their workshops to high schoolers. They spent months developing their workshops and, as the final exam, pitched nine topics to the NSD Racial and Educational Justice Team. The team chose two to be presented at a Student Justice Conference. The topics were algorithm bias and performative versus authentic social media activism.

These workshops were then further developed through an independent study with Tang and six students from the course during winter quarter 2022. “Throughout the quarter, I helped students transition to an educator role,” Tang said. “I started by introducing them to different teaching philosophies and pedagogies, then we learned how to write lesson plans, taking into account the goals, concepts and examples they would want to use in their presentations.”

The educators from the Racial and Educational Justice Team were extremely valuable in this process, Tang said.

“They came in and met with the students every two weeks to give feedback as well as offer their perspective and expertise,” she said. “They were more than just partners or collaborators — they were co-educators.”

Content controls

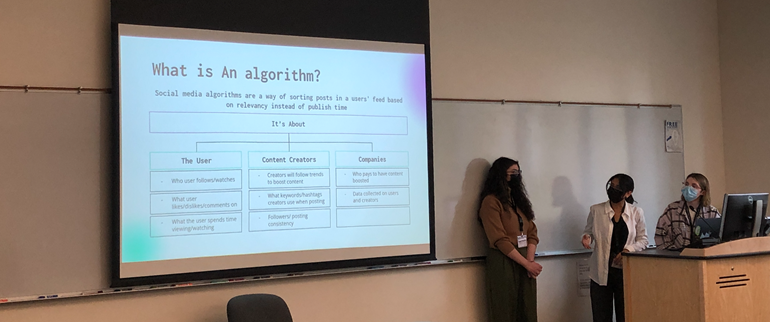

On March 25, after six months of preparation, three students from Tang’s class — Any Chang-Bocanegra , Taylor Dawn Smith and Sydney Stapelman — presented their workshop on algorithm bias to 60 high school students.

One of the first things they instructed participants to do was take out their phones and go into settings to see how much time they spend on their phones. According to a survey published by the nonprofit research organization Common Sense Media, most teenagers spend five and a half hours a day on their screens. But what Tang’s students found to be even more alarming than the time spent on applications, is the lack of control they have in what content they consume while on these platforms.

The control lies instead with the social media algorithms, which decipher what posts get seen — and by whom. “Algorithms are able to create profiles on individuals without them even knowing,” said Chang-Bocanegra. “And they are often unfairly biased against certain groups of people, most often people of color or other underrepresented communities.”

Tang explained that algorithms were made by humans to behave like and affect other humans, and as a result, the technology can be just as flawed as the people who make it. “Because they are made by human beings, they pick up on the social biases and stereotypes that we possess and that are embedded in society,” she said, “which sadly ends up perpetuating the harm that causes.”

Reclaiming power

During their presentation, the UW Bothell students pointed to Addison Rae, a white TikTok influencer who rose to fame in 2021. “She performed eight viral dance trends on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, and no credit was given to the original creators of the dances, who were all people of color,” Dawn Smith explained. “Black content creators frequently get their content stolen without credit, and worse, their posts are frequently hidden or restricted on TikTok.”

Similar issues exist on YouTube. The students featured a lawsuit from 2020 in which Black creators sued the media platform for racial discrimination. “The algorithm systemically removes their content without explanation or limits how much people of color can earn from advertising,” said Dawn Smith. “The company’s response was disappointing. They responded by brushing it off, saying that ‘It’s not like our systems understand race or any of those different demographics’ — when in fact, they do, or at the very least, can.”

To help the high school students learn how to take control of their social media feeds, the presenters proposed algorithm auditing when on various apps. This includes making use of the not interested button, hiding videos and unfollowing users.

“Most everyone uses social media, and it is important to recognize that biases are hidden in plain sight,” said Chang-Bocanegra. “There is a common pattern of racism and discrimination in these algorithms, and we want students to walk away knowing there are ways they can challenge the algorithm bias. If enough people do this, change can be made.”

Media moguls

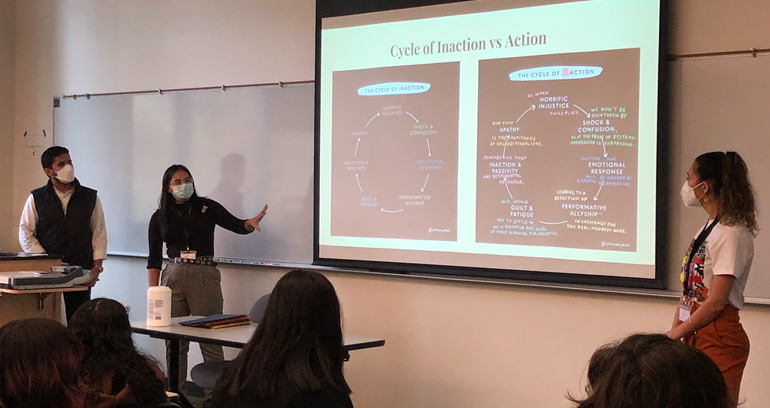

The other group to present was also composed of three UW Bothell students — Muhammad Basbeth, Racquel Farrar and Viola Tabares. Their topic also looked into systemic racism but through the lens of social media activism. “Our goal was to help people be more aware of what is authentic activism versus what is performative,” Tabares said. “Performative is showing off, acting and/or being unempathetic whereas authentic is showing up as an ally, being real and truthful.”

To highlight this, they talked about the cycle of action. Tabares said it starts with injustice and is characterized by four distinct actions: “First, there is recognition that the injustice is not surprising, as racism and systemic oppression is persistent within society. Second, instead of reacting with emotion, an empathic and compassionate response is taken. Third, real, vigorous work begins. And finally, there is the refusal to quit until justice is maintained.”

In contrast, the cycle of inaction is characterized by a person being shocked and confused that injustice took place, reacting emotionally, participating in activism because its “trendy” and stopping when it’s no longer the “cool” thing to do.

The presenters used Kendall Jenner — model, media personality and socialite — and her Pepsi commercial as an example of inaction and performative activism. The ad, which has since been removed, showed Jenner joining a protest and defusing tensions with police officers by handing one a can of Pepsi. “This ad ran in the height of Black anti-police violence protests and diminished the severity and importance of the movement and, ultimately, made light of it,” said Farrar. “After the backlash that ensued, Jenner claimed she didn’t know it would cause harm and said that was never her intention. But the fact of the matter is she did it, and it did cause harm. Her failure to be accountable aligns with performative activism.”

Through their presentation, Tang’s students hope the high schoolers become more critically aware of who is taking part in these justice-oriented conversations and for what reasons. “Social media activism is a really important topic because social media is so relevant. It’s in all of our lives in one way or another, which is why it’s particularly important to pay attention to how people engage on these platforms” said Basbeth. “Content can change our thoughts and opinions if we aren’t hypervigilant.”

Long-lasting learning

Tabares is glad that she took Tang’s class and said it allowed her to engage in research and gave her valuable experience. She is an Educational Studies major and plans to teach students in the future.

“Learning how to transition into that educator role was particularly valuable,” she said. “And I hope the high schoolers learned some valuable things from it as well. I hope they become more aware and that a little bell rings off in their brain when they’re online and remember all that we discussed.

“The things I learned in this class will stay with me a long time — and I hope that’s the case for them, too.”

Learn more about Dr. Min Tang’s work with the Northshore School District during the Husky Highlights seminar taking place over Zoom on Apr. 20 from 4 to 5pm.