Unlike most college campuses, the University of Washington Bothell is nestled next to a wetland. Students, faculty and staff can spend their breaks walking underneath a canopy of trees, surrounded by greenery, listening to the trickle of water.

While the peaceful oasis created by the North Creek Wetland is beneficial to those who are looking to decompress between class periods or work hours, it has an even great value: rare research opportunities.

Dr. Rob Turner, teaching professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences, has been studying water quality on campus since 2007 and has involved hundreds of undergraduate students in his research. “It is a remarkable opportunity for our students to have such easy access to one of the largest wetland restoration projects in the Pacific Northwest.”

Ripple effect

Turner’s students begin their research in his class Environmental Monitoring Practicum, a lab that focuses on water quality. “Students in this course have collected water-quality data from particular locations in the North Creek Wetland year after year,” he said. “That method of collection allows us to measure trends and analyze how things change over time.”

For more than a decade, their research has shown evidence of E. coli in the water. Turner said this is to be expected given the number of crows — as many as 16,000 — that roost nightly in the wetland from dusk to dawn. “Other researchers on campus are studying why the crows have chosen the wetlands for their home,” he said. “We are focused on how to keep their home and our community safe by looking for ways to decrease the levels of E. coli.”

When senior Kyle Quach took this class a year ago, he discovered his passion. “I realized that the research I was doing could have a greater outcome than just getting a good grade, and that motivated me. Knowing I could make a significant difference in the health of our ecosystem left me with a greater drive to succeed,” he said.

At the end of the quarter, Quach, an Earth System Science major, wasn’t ready to stop the work. He joined Turner’s research group of students equally engaged in the cause, and they together continued to look for ways to reduce the bacteria.

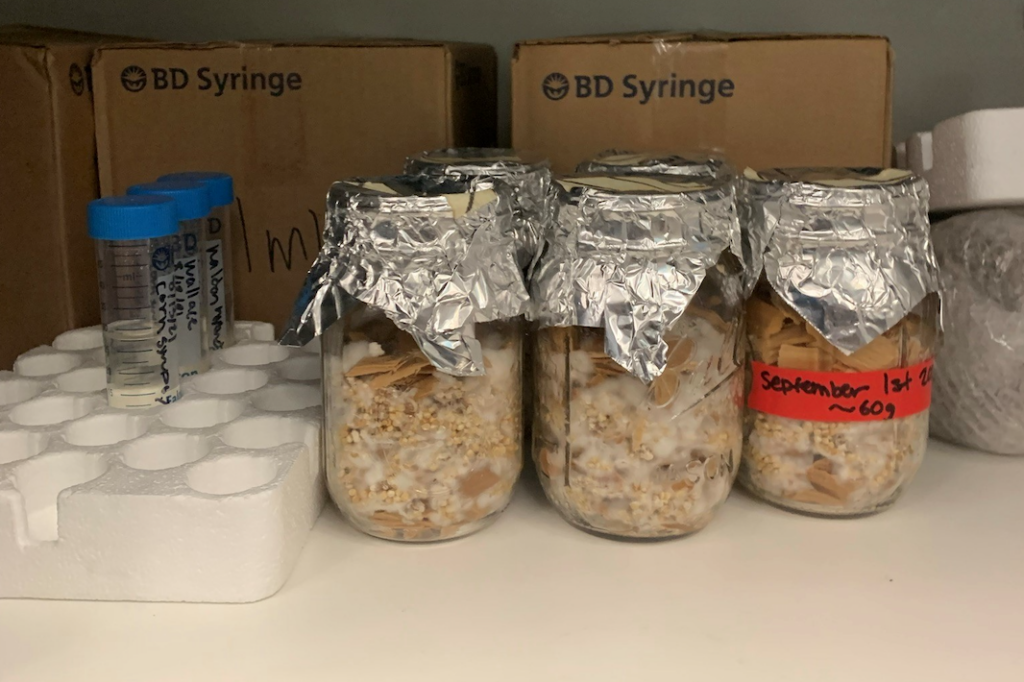

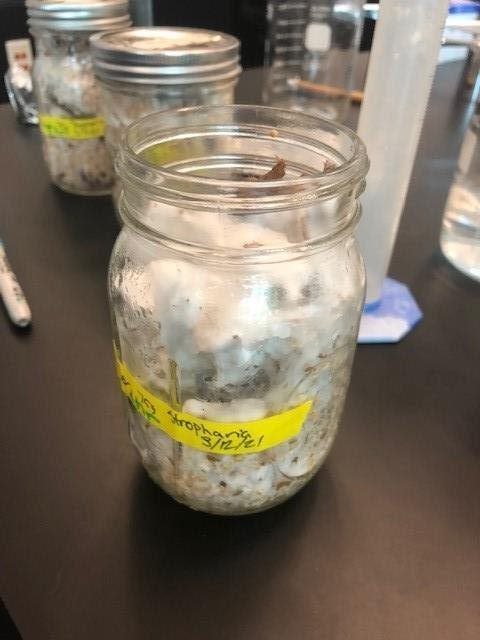

Ali Al-Ameedi, also a senior in ESS, has been part of the research group for nearly a year. He explained that students from a cohort in 2016 found that mushrooms could be a potential solution to decreasing E.coli. “When we filter contaminated water in mycelium (the underground part of the mushroom) and woodchips, it decreases the E. coli,” said Al-Ameedi. “The longer it was immersed, the more the bacteria is reduced.”

Current ideas

Parallel to Turner’s research is that of Keya Sen, lecturer in the School of STEM. Over the last decade, she and Turner have received a series of grants to fund research relating to the impact of crows on water quality and the use of mycelium to remove the contaminants.

Sen and her students are comparing the effectiveness of different mushroom species in decreasing various bacteria, including E.coli. They found that the Stropharia mushrooms yield the most promising results.

Now, the challenge is figuring out how to scale the project up and get enough Stropharia mycelium to clean the stormwater runoff. “The runoff going into North Creek is constantly flowing and constantly saturated in pathogenic bacteria, and the mycelium die off because they can’t keep up,” said Al-Ameedi. “But we keep working on it.”

Alumni Max Llewellyn and Coral Ely are also assisting on the research and brainstorming ways to implement the groups’ findings. One of their ideas is to cover coconut planting discs in mycelium and distribute it into the wetland. “We hope to start this process in the coming months and gain results shortly after,” Llewellyn said. “In the meantime, we remain cautiously optimistic about the results.”

A drop in the bucket

Studying water quality on campus is not just good for the environment, it has also been highly beneficial for students.

“They learn methods of water sample collection and analysis that they go on to use in their careers,” Turner said. “Lots of them work in government agencies or go into consulting. I hear from them every now and again, and am always happy to learn they have continued building on, and using, these skills.”

Al-Ameedi testified to this and said he gained expertise in taking samples, collecting data and using machinery to gauge water characteristics such as pH levels, dissolved oxygen and turbidity.

“Thanks to Dr. Turner and this research opportunity, I have the skills I need to qualify for the kinds of jobs I want to pursue after graduation,” he said. “I am extremely passionate about researching water quality — even if my contributions are just a drop in the bucket. It all adds up. I’m excited to continue this work professionally in the years to come.”