Whether rich or poor, young or old, there is a common experience that humans across the world share: the wonder of the night sky.

In times of loneliness, people gaze up at the stars and find solace in the idea that someone, somewhere, is looking at the same sky, at the same moment. The sky is a place where comfort is found, wishes are made and questions are formed.

Part of what makes it so mesmerizing is that there are far more questions about the night sky than there are answers. Dr. Joey Shapiro Key, assistant professor of physics in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of STEM, has been fascinated by the sky since childhood and has sought answers since adolescence.

She is now paying forward the knowledge from her lifelong curiosity by providing research opportunities to curious students — just as she once was. “It’s great to be able to support students in pursuing their interests,” she said. “I understand their passion and want them to realize just how far it can take them.”

Gravitating toward physics

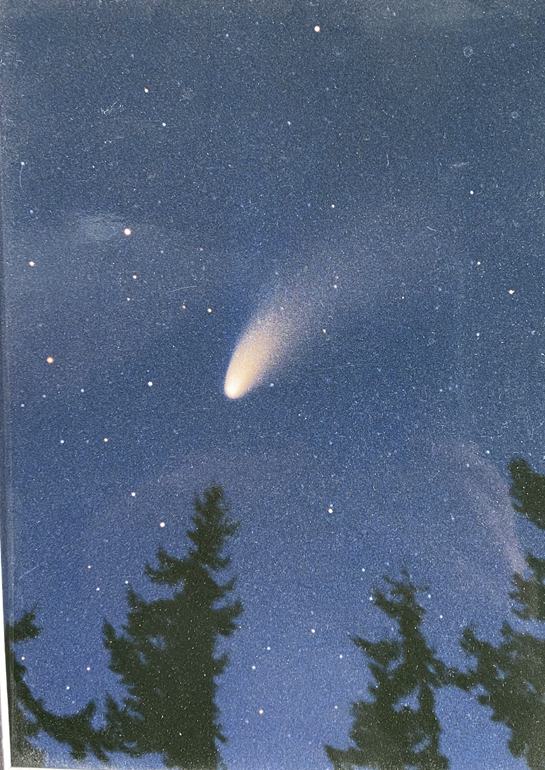

One of Key’s first memories is a road trip from her home on Whidbey Island, Washington, to a desert in California in the early 1980s. Packed in the car with her mother, father and sister, she set out on a 1,000-mile journey to see Halley’s Comet.

“It is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth,” Key said. “It only returns to Earth’s vicinity once every 75 or 76 years, so for most, it’s a once in a lifetime event.”

Growing up to become an astrophysicist, Key has seen many comets through a telescope since but said that her wonder remains. “I haven’t become immune to it yet and don’t think I ever will,” she said. “My amazement actually grows with time.”

Also growing is her community of astrophysicists — thanks in part to her efforts mentoring high school students across the nation who share in her amazement for not just comets but also planets, gravitational waves and black holes. She connects with students in various states through a number of organizations, one of which is the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in Hanford, Washington.

National network

UW Bothell is a member of the LIGO scientific collaboration, and Key is one of the faculty members who works on data analysis for the organization. Key has a national reputation and high school students across the United States seek her out, often saying it’s because they want to “learn from the best.”

Efi Kotsiou, a high school student from New York, was aware of Key’s stature in the field and reached out to her over email. Key helped her work on a science fair project using resources from the Pulsar Science Collaboratory to examine the characteristics of pulsar systems, studying their rotation, masses and what can be observed about them.

Key also sponsors students directly involved in the collaboratory, based in West Virginia. PSC students participate in an online course that teaches them about pulsar science and radio astronomy, and prepares them to become researchers. Once trained, students gain access to radio astronomy data taken by the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, one of the most sensitive instruments in the world for collecting and amplifying the tiny signals from pulsars.

“Working with students is one of the most rewarding parts of my job,” Key said. “I am just as grateful to work with them as they are to work with me.”

What if to what now

Closer to home, Key mentors students from UW Bothell, such as Carol Miu, a returning student at the University. She earned her first bachelor’s in Economics nearly two decades ago and is working as the chief product and analytics officer at PeopleFun, a company that designs mobile games. She decided to return to college to get a bachelor’s in Physics after a year of self-reflection during the pandemic.

“I inherited my love for physics from my dad,” Miu said. “He passed away in 2017, and I found myself really missing him when we went into isolation. There was nothing to distract me from my grief anymore, and I longed to reconnect with him.”

Miu said she grew up learning about Albert Einstein from her father and drawing pictures of the moon. “My dad’s passion was infectious. While I love the career I have now, I always wondered what my life would have been like if I had the confidence to pursue physics in higher education,” she said.

“I was always praised in my economics classes and faced a lot of criticism in my physics classes, and as a result had a lot of self-doubt. Now that I am getting older, I don’t want to live with regret, so I figured why not find out?”

In summer 2020, Miu met Key through the Physics Research Experiences for Undergraduates program at UW Bothell. “I started the program while we were all in quarantine and was carrying a full load while also working full time and caring for my two kids,” she said. “I remember that Dr. Key was so welcoming, inclusive — and just wanted to do whatever she could to support me.”

Bringing diversity to the field

Miu spent the summer under Key’s mentorship, working with data from LIGO to detect gravitational waves, a reaction that occurs when two black holes merge.

“It was such an empowering experience. I didn’t just gain skills, I also gained confidence,” she said. “Prior to this, I never felt welcomed or like I belonged in the physics community, but when Dr. Key took me under her wing that all changed.”

In fact, part of why Key is so passionate about mentorship is because of the exclusivity and consequent lack of diversity in the field. “Some of the most interesting, complicated and hardest problems we are trying to solve are related to physics, whether that be issues related to clean energy production, energy storage or electric vehicles,” Key said. “We really need the brightest minds and the greatest ideas to solve these problems, and we are not accessing all of the human potential that’s out there when the field is dominated by wealthy, white men.”

Key encouraged Miu to join the American Physical Society committee that works on diversity, equity and inclusion. Miu now meets with the committee monthly to discuss different initiatives to support DEI efforts in the physics department at UW Bothell. “It has been so rewarding, and I am so grateful to Dr. Key for getting me involved,” she said. “There aren’t enough words to express how amazing she is and the impact she has had on my life.”

A range of experience

Key herself works to foster diversity in the field, in part by bringing together students of varying ages. Under Key’s guidance, Miu collaborates with high school students more than a decade younger than she is — and loves it.

“That cross pollination is so valuable. What’s so cool about it is that the undergraduates have more life experience and maturity that just comes with age, and then the high school students are just brilliant,” she said. “They learn so quickly and are just phenomenal. I think we inspire and learn from each other in equally important ways.”

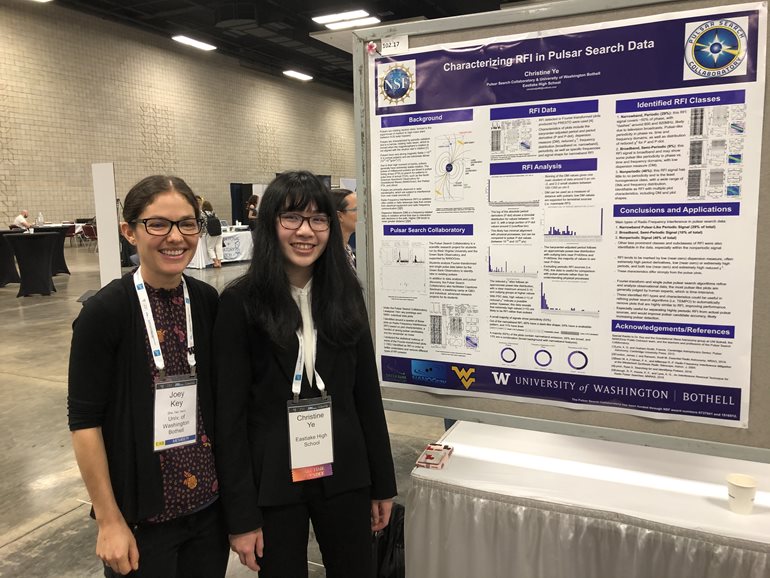

Christine Ye, one of the high school students who works with Mui and other undergraduate students, is one who has benefited from the experience, particularly from Key’s mentorship. Under her guidance, Ye has spent the past two years assisting on multiple projects at PSC, looking at radio data to detect pulsar signals. She also mentors fellow students conducting similar research and is now a leader of the student team of astrophysics researchers (designed for undergraduate students) at North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves, known as NANOGrav.

In addition, Ye is a member of the LIGO scientific collaboration through UW Bothell and has started working with a graduate student at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Together they have written two papers — one of which has been published and the other recently submitted for publication.

“Christine is an amazing story because she has taken every opportunity that she could and has excelled in every one of them,” Key said. “She is extremely impressive.”

Reaching the stars

Ye used all these experiences to enter the Regeneron Science Talent Search, a competition that recognizes and empowers the most promising young scientists in the United States who are creating the ideas and solutions that could solve society’s most urgent challenges. In her application she wrote that Key is the “one person who has been most influential in the development of my scientific career.”

From an original field of more than 1,800 students, Ye was named one of the top 40 finalists in January. Next month, she will travel to Washington, D.C., to participate in the final competition. The top 10 awards range from $40,000 to $250,000.

Key said she is proud of Ye — as she is all of her students. “It’s a joy to witness the work that they do,” she said. “I know that they will each go on to do great things.”