A new online game about whales allows students and average citizens to participate in tracking and efficiently sorting important data about local populations of these marine mammals. No previous scientific research experience required.

Megaptera is a citizen-science game in which players visually and audibly identify whale calls from raw data collected off the coast by the Ocean Observatories Initiative. The game was developed by Dr. Shima Abadi, associate professor in the University of Washington Bothell’s School of STEM, with a team from the UW’s eScience Institute.

The real-time data used in the Tinder-like swipe game is gathered and delivered by the initiative’s network of more than 800 instruments, including hydrophones that record sound waves under water.

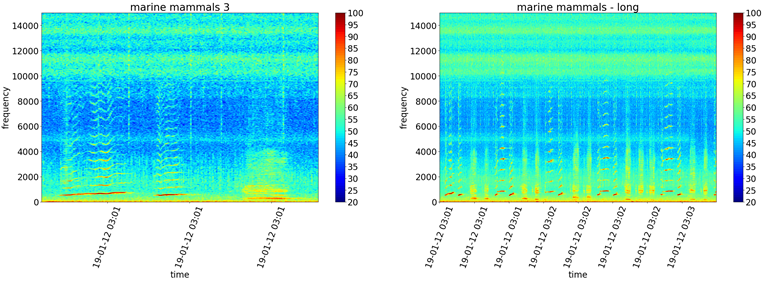

“There are 11 broadband hydrophones measuring acoustic data, and we use that data set to create spectrograms — visual representations of an acoustic signal — for this game,” Abadi said. “If players hear a whale call or they see a whale call in the spectrogram, they can swipe right, say yes, there is a whale call here. If they don’t see anything, they can swipe left.”

Capturing many songs

Megaptera is named for the scientific term to describe groups of humpback whales. As the game tutorial shows, many of the spectrograms of underwater sounds will appear and sound like static. Some spectrograms, however, feature a variety of wavy, vertical lines of different shapes and sizes that represent the clicking sounds of sperm whales, the shrieks of dolphins, the songs of humpbacks and more.

“You see an image that shows frequency on Y axis and time on X axis,” Abadi said. “Even if you don’t listen to the signals, by just looking at the spectrogram you can determine if there’s a whale call there or not.”

Usually, when coupled with audio, the whale-present spectrogram is fairly easy to discern, but for any confusion or curiosity, the game offers a chat feature and the ability to share specific clips so that people can discuss findings with other players. To encourage friendly competition and increase participation, players are labeled based on the number of whale calls they’ve rated.

After all, Abadi said, they didn’t just create this game for fun.

Making meaning of data

Abadi and the eScience Institute had two main goals in creating Megaptera.

“One goal of this game was to expand public participation in marine biology. We can have a booth at different conferences or in high schools and middle schools, for example, and show people how to play this game,” said Abadi. “We want to increase public awareness by engaging the public in science. In the Puget Sound area, people are usually very aware of marine life issues because we live close to the ocean, but that’s not necessarily true for other regions.”

Abadi said that she and the team also hoped to use Megaptera whale songs to answer some long-standing scientific research questions and to train machine learning algorithms to detect whale calls in the hydrophone data that is being continuously recorded — 24/7 — in 11 spots off the coasts of Washington and Oregon.

“A stream of acoustic data is coming in, and if we can develop a machine learning algorithm that automatically detects whale calls it could help policymakers mitigate the effects of man-made noise on marine mammals,” Abadi said. “For example, we can come up with a guideline on how to use this real-time detection algorithm for ships to avoid an area or reduce speed if a whale is detected there.”

More than a game

The team began to investigate ways to automate the identification work because of the sheer volume of data they had to get through — data that, at first, they attempted to sort through themselves.

“The challenge is culling out whale calls from literally years of acoustic data recorded at something like 80,000 samples per second. There are 31 million seconds in a year,” said Rob Fatland, a UW research computing director and a developer who worked on this game as part of the eScience Institute.

“At the Regional Cabled Array observatory off the coast of Oregon,” he added, “the program has been operational since 2015 so you can get a sense of the data volume. Obviously, we can’t sit around for six years listening to hydrophone data playbacks so we started looking into automation methods.”

Aside from offering scientific opportunity, the data, more efficiently identified, could do a lot for the conservation of local marine life.

Responding to the call

While the impact of ambient ocean noise on whales is not yet fully understood — and is difficult to study — recent research has found that an excess of underwater noise can cause certain behavioral and acoustic responses, auditory masking and stress among certain marine animals. Abadi’s own research has taken her UW Bothell students to the Interstate 90 and Highway 520 bridges to analyze the impact of bridge traffic noise on the ecosystem.

At the very least, Fatland (who is the current high-score holder on the game’s leaderboard) finds Megaptera to be a really interesting and enriching pastime that brings him closer to these elusive creatures.

“My favorite thing about Megaptera is listening to the whale calls and trying to guess what they mean,” said Fatland. “The whale calls have a kind of natural reverberation, like one might hear in music performed in a cathedral.”

By building human understanding and compassion for local marine life through this unusual form of citizen science, the creators of Megaptera hope playing the game will help make a difference for underwater mammals — one swipe at a time.

Help identify whale sounds. Individuals, families and classes can sign up here to play Megaptera.