Most of us are surrounded by technology from the moment we wake up — a digital alarm blares, coffee is brewed in an electric pot, our phones light up with notifications reminding us of the meetings we must attend each day. We stare at screens for hours on end, dependent on them for communication, work and even relaxation.

“New technology is changing the way we think, understand, remember, love, politic and play,” said Dr. Ted Hiebert, professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington Bothell. “I mean, let’s be honest, just about anything we do is mediated and mitigated by technology in some way.”

Heads in the Cloud, a Discovery Core class team-taught by Hiebert and Dr. Jin-Kyu Jung, associate professor in the school of IAS, asks the students one, complex question: Is our technological environment simply the new architecture of life, or are there creative ways to think and rethink our possibilities for engagement?

At the core of learning

Hiebert says the term “heads in the clouds” used to be reserved for the romantic daydreamer but not anymore. “Now, we all have our heads in the cloud in one way or another,” he said. “Our heads are immersed in the technologies of daily living — hence the name of the class.”

Discovery Core classes aim to help first-year students transition to academic life. They introduce students to the campus values in small classes where the students can develop relationships with their faculty and classmates. For this particular class, Hiebert and Jung also made a point to incorporate a variety of projects that would facilitate peer discussions. One of the first assignments asked students to make hats out of tinfoil — a metaphor for digital living — and then have someone on campus take their picture.

“It was a bit of trick because we wanted it to be an exercise for students to practice putting themselves out there. It also made them explain the course concept because who wouldn’t ask why someone was walking around wearing a tin foil hat,” Hiebert joked.

Discovery Core classes also, by design, take on topics that call for the faculty and students to move between multiple academic disciplines.

Clash causes creation

Jung’s background is in geography and urban planning, while Hiebert is a photographer and artist. The two professors came together to teach this course because of their differences, not despite them.

“We want the focus to be on points of contention,” Hiebert said. “It is when we clash that interesting things start to happen.”

From their clash in backgrounds, for instance, came the course’s Happy Place assignment that asked students to engage in the abstract concept of happiness. Hiebert describes the project as an intervention.

“We are constantly surrounded by data, virtual signals and quantum particles — but also by creative forms of expression, activism and communication,” he said. “We hope this assignment teaches students how to take control of their surroundings and integrate artistic practices with the critical geographic imagination.”

Making happiness material

Playing off Jung’s expertise in digital mapping, students first mapped happiness by attaching an emotion to a particular place. Some students remember feeling happy when out in the woods. Others recall enjoying the familiar comforts of their beds or family homes that often smelled of homemade meals.

The challenge was to then use art to portray those feelings of happiness in a material form. The catch was that it also had to be accessible to others. “You can’t hold happiness in your hands, take it or even own it, but you can share it,” Hiebert said. “This assignment is asking them to figure out how.”

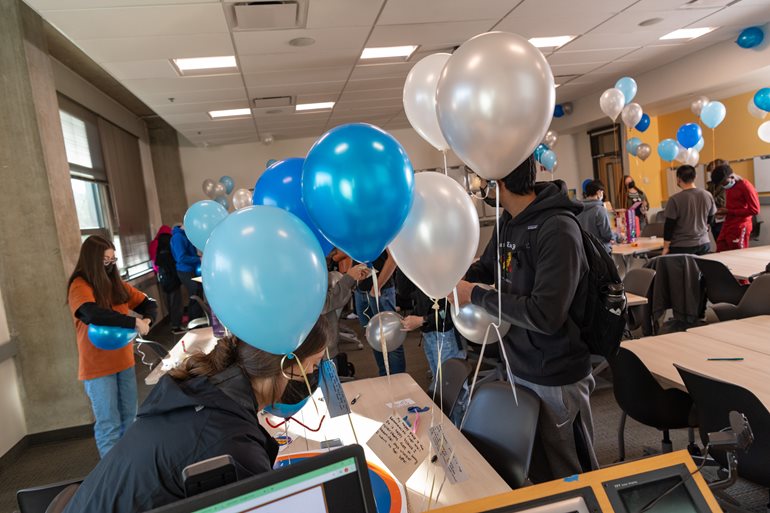

The class considered various forms of artistic expression such as painting, graffiti or making posters, but none resonated. When they came up with the idea of using balloons, however, they immediately knew they had found their answer. “We decided on balloons because they seem to be happy objects or at least objects used in happy contexts,” Hiebert said.

Just as important as the objects themselves was their colors: blue for the sky and white for the clouds. “The cloud is an important metaphor in this class and in the project,” Hiebert said. “It represents that transient space where invisible digital signals — and imaginations — surround us without us always being aware.”

Places for emotion

On the day they planned to conduct their Happy Place field research, students first gathered inside the classroom. Their minds, however, were somewhere else. They put pen to paper and described their happy places on campus — preparing to spread their joy to fellow students, faculty and staff.

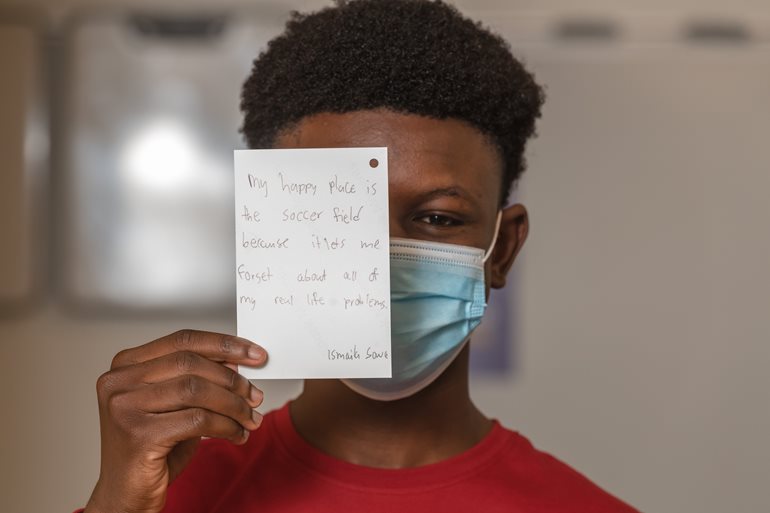

When they finished writing their letters, they inflated their balloons, attached their message and braved the chill of a November morning in Washington. First-year student Ismaila Sowe headed straight for the soccer field.

“It’s where I go to escape my real-life problems,” he said. Sowe started playing as a child and said the sport has helped him cope with everything from anger and frustration to worry and sadness. “It’s how I get through life,” he said.

Jamin Debu, also a first-year student, said his happy place is the second-floor study area in Founders Hall. “It’s a designated eating space where I get to enjoy my two cups of ramen. Then I do my homework and study,” Debu said. “It’s where I feel and perform the best.”

Sharing their joys

After the balloon experiment, students will begin the task of building a “happiness archive” by using GPS tracker tiles with QR codes. Students will each get to leave their tile in a happy place of their choosing for someone else to happen upon it.

Jung explained that on the back of each tile is a QR code that gives the finder access to an online map filled with happiness treasures. Along with the location, it will contain reflections written by students on why those particular places are special to them.

“By creating this intervention, we are arguing that the current technological environment does not have to be the new or permanent architecture of life. The tiles are evidence that there are creative ways to rethink our possibilities for engagement,” Jung said. “The hope is that whoever finds the tile gets to share in the happiness of the person who left it.”

Students plan to leave their tiles in a variety of sites, such as a public park, favorite coffee shop, or nearby beach. Debu said he is planning on leaving his on the Redmond Central Connector Park because he fondly remembers spending one summer day cruising the trail on electric bikes with friends.

“I hope someone finds the tile and enjoys it,” he said. “Spreading good thoughts and happiness is something the world at large needs right now, and I am happy to start doing it.”