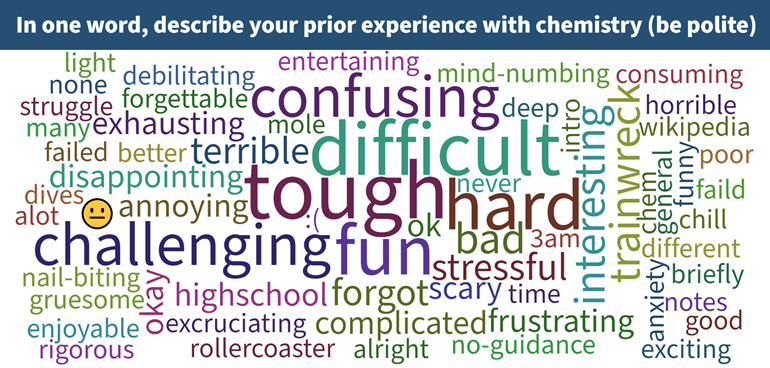

Difficult. Challenging. Impossible.

Those were the words Dr. Charity Lovitt’s students used to describe chemistry in their first week of class. The amount of negativity in her students’ choice of words was overwhelming, she confessed. “It was absolutely horrible.”

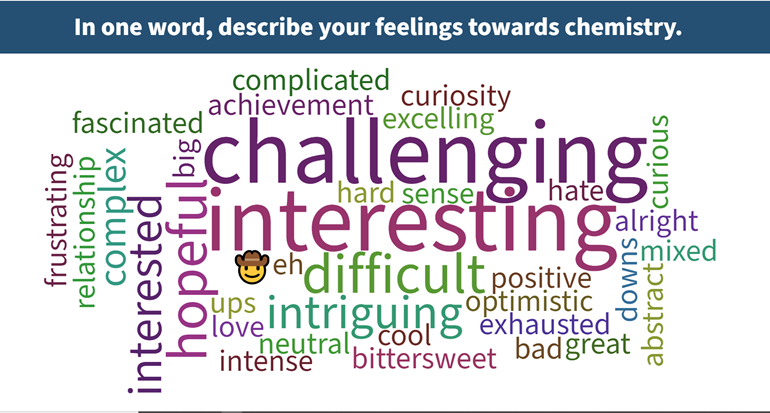

At the end of the course, however, the words changed.

“We still saw difficult and challenging,” Lovitt said, “but we also saw interesting and accomplished. It led to this awesome teachable moment where I could talk to the students and say, ‘Hey, look at how far you have come. This is proof you can do hard things.’”

To be fair, it wasn’t just the UW Bothell students who were up against a challenge last year. Lovitt, associate teaching professor, and Brandon Finley, assistant teaching professor, both in the School of STEM, were faced with teaching a hands-on subject in a remote environment.

In years prior, students would make pancakes in the lab to learn about the chemical reaction between a leavening agent (such as baking soda or baking powder) and an acid ingredient (such as buttermilk). “The reaction produces tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide gas that form throughout the pancake,” Finley said. “The more bubbles you have, the fluffier your pancake will be.”

Teaching this kind of chemistry lesson online, Finley and Lovitt had to make a lot of adjustments. The one thing they wouldn’t compromise on, though, was student engagement. “The course content still had to be exciting to learn,” Finley said.

And it was. By using reflective writing — an unusual approach to learning in STEM — the faculty encouraged their students to use their imagination in a course otherwise firmly grounded in reality. This technique not only engaged students, but it also gave the professors valuable insight into how they could better support learning in their virtual classrooms.

Fence-post problem

One of the ways writing is brought into a chemistry classroom is through problem solving. Finley often asks students to write out answers to obscure problems, hoping to get a sense of how they work through difficulties and what their instincts are.

Two summers ago, Finley was struck with inspiration. When building a fence, he came up with his best question yet. “There was a stubborn fence post that just refused to come out of the ground. Every time I pulled it out, it would just snap right back into place,” he said. Eventually, he started to think about it from a chemistry perspective and realized it was a result of air trapped underground.

“I decided to pose the fence-post predicament to a class to see how students would work through it,” Finley said. “I asked them to write about what approach they would take. I was looking to see if they were using chemical ideas, remembering important principles and making a logical argument.

“Whether they were right or wrong wasn’t as important.”

In the end, about half the students succeeded in figuring out the solution: pouring water into the dirt which released the air bubbles and allowed the fence post to pop right out.

“I love coming up with these kinds of problems because they don’t exist on Google — they just exist in my weird head,” he said. “It is actually a great way to get to know students because it motivates them to come to office hours when they can’t just Google the answer.”

Thinking about thinking

For Lovitt, who is also the associate director for First Year and Pre-Major Programs and the Discovery Core, reflective writing has always been a big part of her teaching practice. “Research shows that reflection is one of the most powerful tools in learning because it’s the ability to not just know what you learn but to reflect on what you’ve learned. It’s a metacognitive process, thinking about thinking,” she said.

She has also found that written reflections can do more than just provide academic insight. They can also provide a window into students’ lives outside of the classroom.

Given the many challenges that students faced in 2020, Lovitt decided to provide a way for her students to self-report any obstacles they were facing that would prevent them from participating in class. She was surprised to find a lot of students were struggling with food insecurity as well as pandemic and non-pandemic related trauma.

“I ended up embedding the links to the Husky Pantry, the CARE Team and the Counseling Center to the writing prompt that asked students about the obstacles they were facing. That way, they didn’t have to self-disclose if they didn’t want to and could then access resources independently,” Lovitt said. “It was helpful for me to know how I can better support my students.

“If I hadn’t provided that space for reflection, I never would have known they were struggling to get their basic needs met.”

Upon her own reflection, Lovitt created a token system that would support students in completing their assignments. She gave each student three tokens to exchange for an extension on any quiz or video assignment up until the last day of class. “This was something they could activate at any time, no explanation needed,” Lovitt said. “It was a great way to create more equity in the classroom.”

For third-year student Andrew Carrill, the token system helped take the edge off. “There were just so many things to be stressed out over the past year,” he said. “It was nice that assignments didn’t have to be one of them.

“It was a really thoughtful and considerate thing of Dr. Lovitt to do,” he added.

Breaking out of the box

For the class final, Lovitt had students do a reflection-based presentation with only three slides to address what they used to think, what they now think and what they are going to do next. Lovitt said it was the coolest last class of chemistry that she has ever taught.

“Giving them that project was really rewarding as a professor,” she said, “and the memes the students included were an awesome bonus.”

Carrill said the structure of the final helped him simplify complex ideas. “It was challenging only being able to use three slides. It made me think hard about what the most important information was to convey and how to express it in only a few sentences,” he said. “Having to simplify complicated processes forced me to have a detailed understanding of how chemistry works. I think that will help me retain the information as time goes on.”

In Finley’s class, students were given different options — writing or making a poster — to demonstrate their learning for the final. “I wanted to allow students to be creative in a class that is often viewed as rigid and purely scientific,” he said.

“It’s time we break out of that box a bit.”