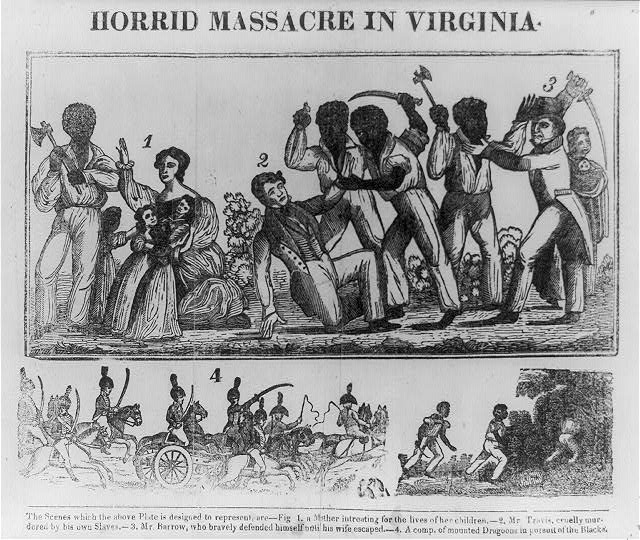

Nat Turner led a slave rebellion in 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia. Dozens of people were killed. More were killed in the aftermath, including Turner who was hanged. That much is agreed upon, but nearly everything else about the rebellion is hotly debated or represented through politics and art, said Dr. Linda Watts, professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences at the University of Washington Bothell.

“We have almost nothing that comes directly from Nat Turner. We see him refracted through other people’s accounts,” said Watts, who is teaching a course called, Remembering Nat Turner: Studies in Historical Memory and Representation.

Watts challenges her students to become historical detectives. They not only investigate the historic situation, they also analyze its implications in artists’ imaginations.

“Playwrights, poets and novelists, artists, rappers and spoken word artists, dramatists all continue to retell the story of Nat Turner,” she said.

Historian’s dilemma

Bridging the social sciences and humanities, the Nat Turner slave rebellion is a good subject for Discovery Core, a program at UW Bothell that helps first-year students transition to college, learn the University’s multi-discipline approach and consider other fields before they decide on a major.

Watts, who has been at UW Bothell since 1999, has also taught versions of the Nat Turner Rebellion in higher-level courses. It’s a historian’s dilemma, she said: How do you tell that story properly, responsibly, accurately? How do you tell a story of enslaved people when they were often denied literacy?

Teaching the subject to Discovery Core students is an added attraction for Watts.

“I love the way that brand-new undergraduates are maybe a little timid but very game,” Watts said. “They’re willing to try something.”

In contrast to a survey course that slogs through a broad swath of history, Watts is teaching history using a case-study method — and sticking a pin in the map at Southampton, Virginia. She focuses on one incident and the repercussions; 1831 is the entire timeline.

“You can get to know quite a lot about history by looking at one pivotal moment,” Watts said. “It’s like a stone in the water and the ripples out from that stone.”

Rebellion, insurrection

This winter quarter course about the Nat Turner rebellion started the same week as violent protesters broke into the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

“This is the first time I’ve taught it coincident with a U.S. insurrection,” said Watts. “That gave it a different charge.”

Former students Watts taught also mentioned Nat Turner when commenting on social media about the violence in the nation’s capital, she said, adding it was gratifying to know that work they had done as long as 15 years ago was still a reference for them.

“The Nat Turner course gives people a way to think about culture that is very focused on questions that are live questions for them,” Watts said. “We end up talking about whether violence is ever warranted, as a first step or as a response to violence.”

The class also prompts students to discuss the agency of enslaved people and how they resisted the conditions of a society in which they had the legal standing of property.

The period before the Civil War echoes modern times as people try to make sense of division and dissent, said Watts, noting that in his inaugural address Joe Biden said, “End this uncivil war.”

Changing perspectives

Alumna Marya Dominik (Society, Ethics & Human Behavior ’06) says Nat Turner was one of the first courses she took at UW Bothell, and she remembers how it changed her perspective on slavery and emancipation.

“The course really opened my eyes about what I did not know, and of course made me do some self-reflection on why I allowed myself to have such a limited view of what had happened,” said Dominik, who remains in contact with Watts on social media.

Dominik said Watts encouraged students in the class to notice what isn’t in the historical records.

“Just like the stats course at UW Bothell has me looking at data in news articles with a critical eye, the Nat Turner course taught me to look for what they leave out and to really dig deep and question why,” Dominik said.

The events of Jan. 6 brought the course back to mind for Dominik.

“When the attack happened, I was really uncomfortable with the term insurrection being used by the press,” she said. “I realized that I think of Nat Turner’s insurrection as fighting for good, and I could not view what the people who attacked our democracy were doing as anything good.”

A place of possibility

In spring quarter, Watts will be teaching another Discovery Core course, Reading and Writing: The Literature of Social Engagement. It’s another example of understanding complex events through the humanities.

Although intended for first-year students, Discovery Core courses are open to all majors, Watts said. “It’s a place of possibility.”