By Douglas Esser

A film produced remotely by University of Washington Bothell students — who didn’t meet face to face because of pandemic restrictions — won a medal at the ZEBRA Poetry Film Festival in Berlin.

“Delirium” was produced as a class project by eight students in the spring quarter Competitive Filmmaking course taught by Masahiro Sugano, artist in residence in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

The festival’s artistic director and one of the judges, Thomas Zandegiacomo, said the students studied the poem and incorporated a wealth of subtle images and allusions in their interpretation.

“This is what makes the film so special, and you enjoy discovering new things in the film,” Zandegiacomo said. “The film does not just reproduce the words of the poem but adds another level to it. The whole thing also takes place in a very fresh and new film language. By shifting the plot into our everyday life or into an apartment, the film brings the distant images and metaphors of the poem very close to us.”

‘Delirium’

ZEBRA

Held every two years, the ZEBRA festival invites short films based on poems. It had more than 2,000 entries for 2020. In addition, this year the festival invited interpretations of the poem “Lethe” by the Botswana poet Tjawangwa Dema. In Greek mythology, Lethe is the personification of oblivion.

“Delirium” was selected as one of the three best films that used audio of the poem read by Dema. The other winners were from schools in Germany and Poland. Ordinarily, the winning filmmakers would have been invited to Berlin for a showing and discussion with the poet during the festival, Nov. 19-22. Because of the coronavirus, all the showings shifted online.

7-minute film

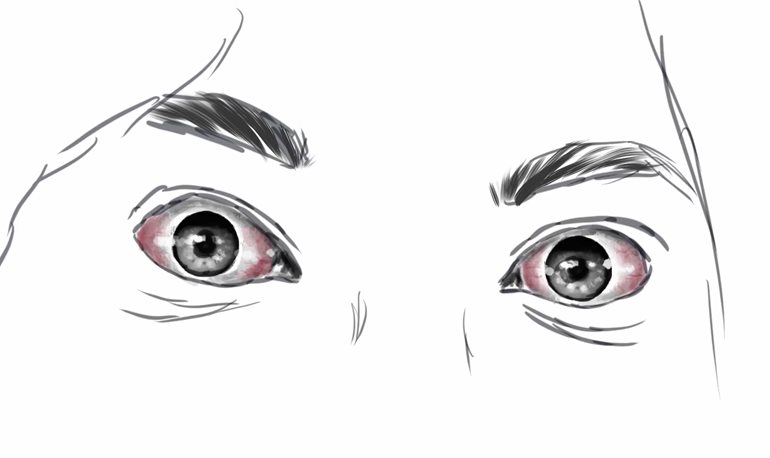

The seven-minute “Delirium” mostly presents the point of view of the main character — seeing objects in her hands as she goes through the process of making morning coffee and pouring a bowl of cereal and milk. The sequence is repeated with disturbing variations, interspersed with dream-like animations to sounds of the spoken poem.

After a normal breakfast, in the next version there are earthworms in the coffee grounds. Next time, the cereal turns into nuts and bolts. Then, the carton of milk becomes engine oil. Oddly, the main character accepts the changes as part of her routine.

“It gets weirder and weirder,” said Sugano. A quiet ending makes viewers think about what happened.

Multiple roles

Thelma Tunyi, the only person seen in the film, stars and was a director, the cinematographer and an animator.

To record herself, Tunyi wore a helmet rigged up with a camera. Like other parts of the production, scenes often had to be redone to meet the artistic standards of Sugano, who the students call Sensei, or teacher. The hard work was worth it because creating a film that could compete in festivals gave her confidence, Tunyi said.

“I think it’s amazing what everyone did through Zoom. It’s unbelievable when you think about it now,” she said. “It shows you everything is possible if you set your mind to it.”

Team Delirium

The producer, Chelsea Moser connected everyone and kept them on schedule. “I’m so proud of everyone and everything they achieved because I was like the manager, and it’s phenomenal.”

Shanley Fermin was the other director and film editor. Brianna Hinds was one of the art directors and one of three music and sound designers.

Yidong Lin and Ramilya Salem were animators along with Tunyi. Salem also operated the rotoscope animation tool. Krystal Wan was responsible for sound effects as well as music and sound design, along with Hinds and Lin.

All but two of the filmmakers were 2020 graduates in Media & Communication Studies. Lin and Wan are current MCS seniors.

Embracing the challenge

The writers, Moser and Jonathan Wiedemann, who also was an art director, interpreted the poem with ideas of repetition and the deterioration of memory, Moser said. “I read it more as the endless loop you can get into in your mind and what that looks like.” The film also could be interpreted as related to the pandemic, Moser said.

Isolation was incorporated into the production, which reflects Sugano’s philosophy of filmmaking: When you encounter adversity, make it the center of your art. If you only have two colors on your palette, make a two-color painting. If you don’t have the lead actor, build a story that’s missing the main character, said Sugano, who has been at UW Bothell since 2017.

“Very often we have attachments to a notion and complain about what we don’t have — what we think we should have. Instead, if you don’t have it, show it. Make that the center of the story,” Sugano said. “We turned our challenge into the core of our aesthetic.”

Sugano teaches filmmaking and Japanese popular culture history courses for students majoring in Media & Communication Studies. Sugano’s studio partner, Anida Yoeu Ali, an IAS senior artist in residence, helped design the course, promoted the film and is entering it in more festival competitions.

Professional work

This was Sugano’s first time teaching Competitive Filmmaking. The goal was to win festival medals that students can cite in their resumes or portfolios for employers. “I really want to help the students with that. I want them to be able to say, ‘This is what I accomplished,’” Sugano said.

He ran the project as a real film production company. Text messages about the work often continued into late nights and weekends.

“I’ve always wanted to lead a small group of students to produce something of very good quality,” he said. “With this class, the level was extremely high.”

Winning the ZEBRA award is testimony that students can meet standards recognized outside the school, Sugano said. “I wanted to put the product first and then see what they could learn, and I think they learned a great deal.”

Professional career

The experience was the deciding factor for Moser to work in film full time. She recently completed work on a national commercial.

“I really worked with Sensei in a director-producer relationship rather than a student-teacher relationship. He taught me a lot about the dynamics of being in an actual film crew and what that could look like and feel like and what your responsibilities are,” she said. “He really pushed us to see if we could handle it.

“I think it was invaluable. I learned stuff I would have never learned in a normal classroom.”