Researchers at the University of Washington Bothell have received a grant from the National Security Agency to model how a next-generation 911 system would operate in an emergency, such as an earthquake, and how it would react to a cybersecurity attack.

The one-year grant brings $150,000, with an optional second year for a total of $300,000, to Mike Stiber, professor of Computing & Software Systems in the School of STEM. Stiber is the principal investigator with co-investigator Barbara Endicott-Popovsky, executive director of the Center for Information Assurance & Cybersecurity at UW Bothell. Through CIAC, the University of Washington is a federally designated center of academic excellence in cybersecurity education and in research — the only one in the state, Endicott-Popovsky said.

She said the grant could lead to more funding for cybersecurity studies and help train more professionals for the field where there are already more than half a million job openings, according to Cyberseek.org. Meanwhile, the Department of Homeland Security is drawing attention to cyber threats by making October National Cybersecurity Awareness Month.

Time to upgrade 911

“Cyber issues are so prevalent today, you don’t have to know anything about computers to know it’s a horrible situation,” Stiber said. “This is one of the major problems of our age.”

The emergency 911 system on which people rely to call medics, firefighters and police is increasingly vulnerable as internet and wireless technologies evolve. When people had only a landline in their homes, they would pick up the phone, dial 911 and reach the emergency dispatcher.

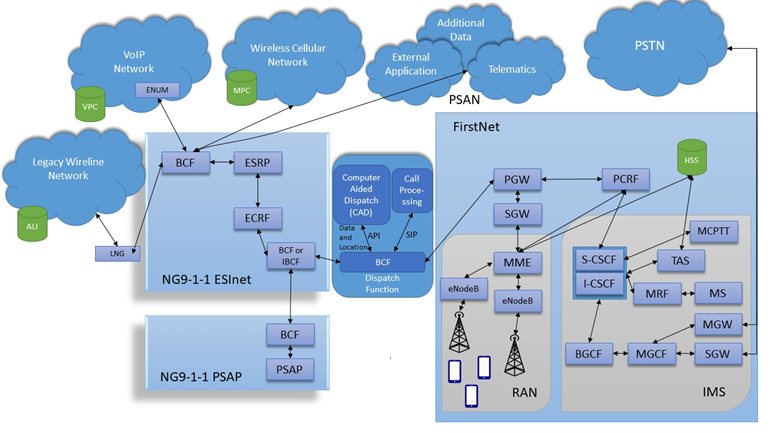

Now, a 911 dispatcher’s workstation has multiple display screens, radios and phones cobbled together from subsystems, and none of them interoperate with each other, Stiber said. Callers are using mobile devices, and they may be texting or trying to send photos and video.

“The human being is interfacing all these systems together in their brain,” Stiber said. “The dispatchers are so loaded down they can’t be thinking about what’s the pattern of activity and is this real or is somebody doing something nefarious.”

Plus, the volume of calls will only speed up with 5G technology and internet-connected sensors that could, for example, notify 911 when bridges fail in an earthquake. Older systems aren’t ready for that or for the people looking to cause mischief or havoc.

“Suddenly, what the cybersecurity expert would call the attack surface is much, much larger,” Stiber said.

Added Endicott-Popovsky, “The vulnerabilities of adopting technology have not been solved and probably won’t be in the near future.”

A network is a network

Stiber, who has been at UW Bothell since 1997, researches computational neuroscience and high-performance computing. About a decade ago, his research laboratory developed a program called BrainGrid to model neural networks. The genesis of the NSA project was realizing BrainGrid could be applied to a different problem.

“To simulate a 911 system, you need to do the same things you do to simulate nervous systems,” he said. “BrainGrid isn’t just for brains anymore.”

The simulation testbed is being revamped in collaboration with a representative of the North East King County Regional Public Safety Communication Agency (NORCOM) based in Bellevue, Washington, where the 911 system was temporarily overwhelmed on May 31 during a protest and mall looting.

The second year of the NSA grant would add a cyberattack to the exercise and could involve T-Mobile, a University partner in cybersecurity internships.

“What we hope to do is demonstrate some of the weaknesses of the current system and contribute to the conversation about next-generation 911 — what needs to be done to make it a more unified, purposefully engineered system,” Stiber said.

Not good enough

Because the 911 system is working OK, government and industry haven’t paid enough attention to it, particularly its cybersecurity vulnerabilities, Stiber said. A “bad actor” could take advantage of a crisis, for example, to generate spurious calls and cripple 911. The model Stiber is developing will be able to look at patterns of activity and recognize when something unusual is potentially a cybersecurity threat.

“Basically 911 works, but I’m going on record now,” Endicott-Popovsky said. “911 is going to face incredible challenges.”

October is National Cyber Security Awareness Month — Get tips, resources

Learn how to protect your personal and UW institutional information from online threats with these tips from the Office of the Chief Information Security Officer.