By Douglas Esser

A virtual reality (VR) program developed by two Computer Science & Software Engineering majors might be used to train firefighters to run the pump control panel on a fire engine, saving time, expense and water.

Isaiah Snow said the idea for a simulation occurred to him because his father is a Seattle firefighter. When Isaiah first told him about his virtual reality work, Craig Snow said he thought it was a game.

“When he explained what could be done with it, I thought it would make a very handy training tool for the fire department,” said Craig Snow, who has been a firefighter for 21 years.

The VR program started to take form this summer as a capstone project for Isaiah Snow, who graduates after autumn quarter, and Kellan Blake, who graduated after summer quarter.

Kelvin Sung, a professor in the Computing and Software Systems division of the School of STEM, supervised the project. He also taught the 3D computer graphic and computer game design courses where Snow and Blake learned the concepts.

“Before that class,” Blake said, “I never made a project on this scale with all these 3D objects interacting with each other in different ways.”

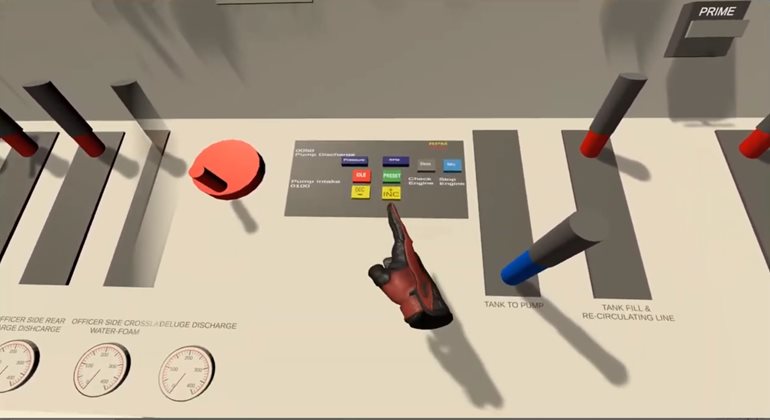

The view from VR

In the fire engine simulation, the VR control panel does look a little like part of a game. Wearing a headset, the user controls a hand hovering over the panel. Push a button and hear the engine noise. Pull a lever or rotate a knob to control the water flow. Balance pressures and supply multiple fire hoses. Watch for warnings. An alert pops up on a screen: RPM is too high!

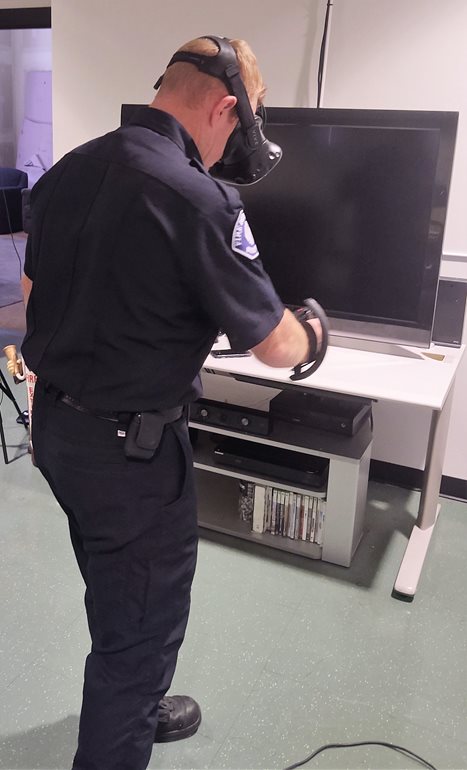

The system uses a Vive headset and Steam Valve Index controllers, which match individual finger motions. “When I want to pick something up, I just grab it,” Isaiah Snow said. “It’s easy for people to understand how those work.”

Craig Snow works on a ladder truck, which does not have a pump, but he was the primary tester at home for the VR program. “I knew it would be interactive and interesting and fun to use, but the level of realism kind of blew me away,” he said.

Much more prepared

Not every firefighter can train to operate a pump panel, Craig Snow said. Operators need to learn hydraulics and the math involved in managing pressure and flow for multiple hoses. In real life, such practice typically requires the expense of an out-of-service training day, plus using lots of water.

The VR program would allow a firefighter to learn the basics and go through the motions on a computer at a fire station or at home “so that when you go out and flow water for real, you’re just that much more prepared,” Craig Snow said.

Isaiah Snow planned to show the VR program to a fire department official, and then they could decide where the project would go from there.

“It’s a good feeling to see him tackle such a difficult project and really do a professional job,” his father said. “His mom and I are very proud of him.”

Software for starters

Isaiah Snow plans to continue developing the program and adding details and features.

“The hope, once everything is modeled correctly, is that we actually see a fire running in the background and other simulated firefighters — communicating with the pump operator to verify their hose is getting the proper discharge and the stream is being maintained properly — and that they can see a fire dying down.”

He hopes the program would be useful to fire departments beyond Seattle. Similar VR control panels could be made for any model fire engine and possibly be included in the sale of the apparatus. “And I can’t see why the software can’t be extended out to paramedics and emergency services,” said Snow, who plans to join the Navy, where he expects to work in computer science.

Let’s hear it

Snow and Blake took an early version of their project to a Seattle fire station where an experienced pump operator provided some valuable feedback: It needed sound. Firefighters need to hear the engine to inform them how the pump is running. In silence, the experience was too unreal.

“Going to the fire station and getting the feedback from the pump operator definitely improved the project,” said Blake.

It took the students about a week to add audio to the simulation. Snow recorded low, medium and high RPM engine noise from the internet and interpolated it in the software. Now, when the operator discharges more water and the pump RPM goes up, the sound matches.

“I didn’t realize how sound was so important in this case,” said Sung, comparing it to shadowing in computer graphics, which is not considered an afterthought or just a cool detail. “It’s very important to convey where objects are in 3D space.”

Design by feedback

The feedback on sound was a valuable lesson in software design, an industry where some techies might prioritize the latest technology over the experience of users, Sung said. “Sometimes students defend their work saying, ‘You’re using it wrong.’ A lot of computer companies do that: ‘Here’s our feature. This is how you should use it,’” he said. “Anything you do that goes out in the real world, make sure you understand the user without being defensive.”

Blake said the capstone project gave him that experience.

“Before, you made the program for the teacher. You didn’t make it for somebody who actually needed it to do something,” said Blake, who is looking for a job or internship in software engineering. “It’s helped me to think of things in terms of how to make this easier for the user, rather than how can I program this in the easiest way possible.”