Melanie Malone researches the presence of contaminants in urban community gardens, and it is research that has taken on even greater significance recently as more people begin tilling their own backyards or neighborhood plots to help them through the coronavirus pandemic.

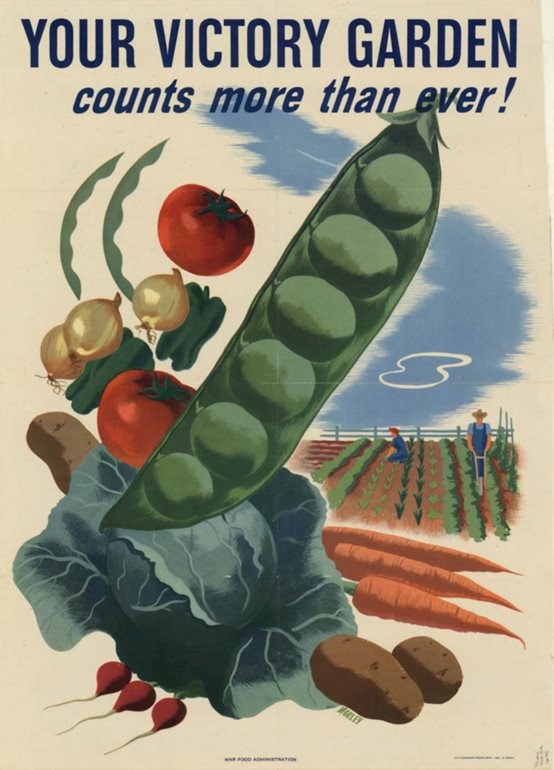

It’s not only practical to harvest your own vegetables, but it also provides mental health benefits, she said, a little like the victory gardens during World War II.

“Everybody is worried the next Great Depression is coming, so victory gardens are very much a thing right now. If people are involved in their community garden, they’re out there even more.

“And if not, they’re trying to get into community gardening,” said Malone, an assistant professor in UW Bothell’s School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences.

Inside, looking out

Malone, who has previously worked as an environmental consultant in Portland, has been at UW Bothell since autumn 2018. She has taught critical physical geography, environmental justice, intermediate geographic information systems and environmental geography.

With the campus on restricted operations, it has been hard for Malone to stay inside this spring quarter and teach independent studies students online. Normally, she would have a whole class outside, collecting soil samples, taking measurements and doing interviews at community gardens throughout Seattle.

This summer, she hopes she and her students can resume the research that is supported this year with a grant of nearly $40,000 from the Royalty Research Fund. The UW program is funded from royalties and licensing fees generated by the University’s technology transfer program.

“I’m still planning to do it all,” she said.

Common contaminants

Nine community gardens in Seattle and five in Brooklyn, New York, that are tested by a colleague provide her research samples. But it was the Farm on the UW Bothell campus where she first gathered samples for her current research project and where she trains students to take soil samples.

Unfortunately, Malone found all those gardens are contaminated, even though they all are organic. The soil on campus, where groundskeepers avoid using pesticides and herbicides, has the same contaminants, Malone said.

“I haven’t found any that don’t,” she said, citing petroleum, lead, arsenic and a chemical used in the popular weed killer Roundup.

“One of the most interesting questions for me is figuring out where the contaminants come from,” said Malone.

The most common question she hears from gardeners is whether or not they are eating contaminants when they eat their garden plants. “We’re doing everything we can, ” they ask. “How is this still coming in?”

Chemical rainfall

Research surveys should help in answering these kinds of questions, but already Malone suspects that some sources might be composted food scraps from nonorganic sources, runoff from neighboring properties and chemical pervasiveness in the environment.

“Roundup literally rains down on us,” she said, mentioning other studies that have found it in the atmosphere and rainfall.

To limit contaminants, she advises, gardeners should buy only organic produce if they can afford it. In the garden, they should work as much organic matter into the soil as possible, making sure that the manure fertilizer they use does not come from farm animals that were given antibiotics or contaminated feed.

“Being familiar with the sources of what you’re getting is really important,” Malone said. “My surveys will be trying to figure out where people get everything from and then figure out how we can get the level of contaminants down.”

Testing made possible

The UW grant is essential to her research because soil samples are expensive to process, Malone said. The cheapest are $100 per sample and detecting Roundup, for example, can cost $400 per sample.

She also needs to have garden plants tested. “A lot of the gardeners have been asking about that,” Malone said. “It gives everybody peace of mind to find out: Is my onion in the ground contaminated? Are my raspberries?”

The grant will pay for processing soil samples and plants this summer. Malone says she can hardly wait to get out to the gardens herself with her interns, if possible.

“One of the things I like about teaching here is having students involved in the research,” Malone said.

Particularly these days, she also likes to encourage people to have successful, healthy victory gardens.

“It’s one of the most important parts for me, because we’re in such a crisis mode. Not everybody has access to fresh fruit and produce. I think it’s really important, and I think it’s important for people to know what they’re eating, too,” Malone said. “That’s the environmental justice component for me.”