The University of Washington Bothell’s Makerspace may not be open for business as usual these days, given restrictions due to the coronavirus pandemic, but it that does not mean all activity has stopped in the Discovery Hall workshop.

Even though classes are being held in a remote learning environment, students can submit online requests for staff at the Makerspace to help fabricate parts needed for their projects.

The staff is also now turning out parts for face shields to help protect doctors and nurses at the UW School of Medicine, Harborview Medical Center and other facilities in the UW Medicine system.

How can we help?

When it became apparent that the coronavirus was causing a shortage of personal protective equipment for health care workers, faculty started thinking about how UW Bothell could rapidly deploy equipment in the Makerspace to support the medical community.

Initially it was the shortage of N95 masks that prompted Jody Early, an associate professor in the School of Nursing & Health Studies, and Pierre Mourad, a professor in the School of STEM at UW Bothell and neurological surgery professor at the UW in Seattle, to engage a number of colleagues in the effort. This included Rafael Silva, the Makerspace operations manager; Troy Dunmire, the mechanical engineering lab manager; and Cinnamon Hillyard, the interim associate vice chancellor for undergraduate learning.

Quickly, the effort began pulling in more interested faculty and staff at UW Tacoma, the UW in Seattle and at other organizations.

Focus on face shields

As people got organized and it appeared the state of Washington had better options to get more N95 masks, the team decided to switch to making face shields or visors that cover the entire face.

Mourad turned for help to Design that Matters, a Redmond-based nonprofit that typically applies rapid prototyping and human-centered design to medical devices in low-resource settings.

The goal was an easy-to-fabricate design that could be used to make face shields that would help protect health care workers until manufacturers caught up with growing demand. The shield had to serve as a barrier against exposure while providing ventilation. It had to be comfortable, easy to put on and take off. It also had to be re-usable for a single user.

“It was designed so that someone with access to a 3D printer and office supplies can build it,” Mourad said.

How to make a face shield

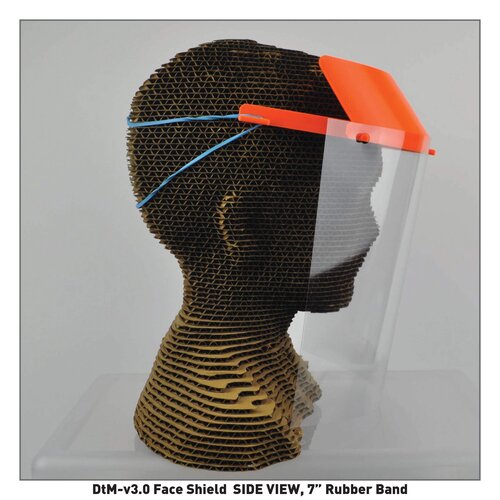

There are three parts to the face shield: the headband that sits on the forehead, elastic that holds it to the head and the clear shield that covers the face. The Makerspace 3D printers produced the headbands. The elastic could be rubber bands. And the clear plastic could be a letter-size transparency or file covers available at most office supply or drug stores.

Because of the size of the headband, only two of the 11 Makerspace printers could be used, said Silva, who tapped some leftover supplies of filament, the raw material that goes into the printers. As of April 8, Silva had printed 26 headbands and planned to continue until April 15, producing another 26.

“It was a positive experience to participate in the initiatives to help on addressing the shortage of medical supplies,” said Silva, adding it was “eye-opening” to see the complex logistics required to produce a reliable piece of medical equipment during a pandemic.

Assembly, distribution

The head band is printed with three pegs or hooks, spaced at the same distance as the holes from a three-hole punch. So, the clear plastic can be punched to snap onto the headband.

At UW Tacoma, Matt Tolentino, assistant professor, and Bob Landowski, lab manager, led the 3D printing effort in the School of Engineering & Technology. The parts from UW Tacoma and UW Bothell were added to the effort at UW Seattle where they were assembled into complete face shields and distributed to UW hospitals and clinics.

As of April 8, Mourad reported, the entire tri-campus DIY community produced 500 face shields.

“I’m very pleased we had the ability to contribute to help our medical colleagues,” he said. “It’s a great example of community-based scholarship and efforts, which are a hallmark of our campus.”

Many hands

Multiple clinical and engineering hands led to the design, Mourad said. They included Timothy Prestero, the CEO of Design that Matters; Elizabeth Johansen of the Boston-area Spark Health Design; and Dmitry Levin of the UW School of Medicine, who led efforts that involved the maker community on the UW Seattle, Bothell and Tacoma campuses.

Prestero helped lead the design of the face shield with clinical input from Vanessa Makarewicz, infection prevention and control manager at Harborview Medical Center. Mourad said Drs. Paul Currier and Kristian Olson of Massachusetts General Hospital also provided important feedback.

Johansen developed the use case analysis that led to this final design. David Packman, a Microsoft product manager, came up with the backwards visor solution to the problem of “droplet rain from above.”

Through a connection with Prestero, the School of Medicine and Boeing teamed up to support Boeing’s possible production of these shields, with discussions on-going, Mourad said.