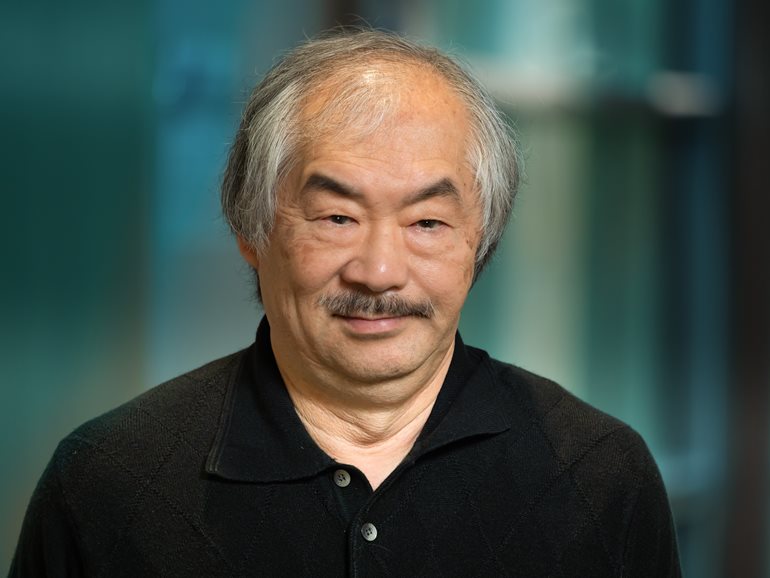

By Kyle Kinoshita

Teaching future school leaders in the principal program at UW Bothell’s School of Educational Studies, I tell them that leadership is hard, complex, with many tests of commitment and values. A part of their learning is about the “Power of Story,” personal narratives helping to discover the bedrock of who they are as leaders. I tell them these stories can also serve to communicate to others their authenticity and willingness to give of themselves.

In class, I share my family stories to illuminate my own foundation in social justice. One story is that of my mother, Cherry Tanaka Kinoshita, who passed away in 2008. Though her story is from the last century, it has deep relevance today.

Cherry grew up in Seattle’s Green Lake neighborhood, where my Japanese immigrant grandparents operated a dry-cleaning business. She graduated from Lincoln High School in 1941, an all-American girl with a high grade-point average and big dreams but no money for college. Before she graduated, she tried to think of ways to finance her education, asking her high school counselor about learning secretarial skills. She was told she could try, but no one would ever hire an Asian girl as a secretary. She was at a loss for what to do.

In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, plunging the United States into World War II. On top of racism directed at Japanese Americans as Asian immigrants, the full fury of anti-Japanese xenophobia resulting from international tensions of the 1930s was unleashed.

The next chapter of Cherry’s story was shared by 110,000 individuals — two-thirds of them American citizens by birth — who were incarcerated in prison camps in 1942. The entire population of West Coast Japanese Americans was forcibly removed, despite no known cases of sabotage and an earlier assessment that they were overwhelming loyal. America was also at war with Germany and Italy, but no similar treatment was meted out to those communities of national origin.

Decades after, a 1983 U.S. Congressional report concluded that there was no national security justification for the incarceration, but that a combination of “race prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political will” led to one of the most egregious violations of constitutional rights in U.S. history.

But what makes Cherry’s story remarkable is not her wartime experience but what followed. In the 1970s, she and a small group of members of Seattle’s Japanese American Citizens League, influenced by the civil rights movement, asked, “How can we right this historical wrong?”

Cherry and her group spent much of the ’70s stubbornly mobilizing others to push the U.S. government to address reparations. Opposition in the early years came not from whites, but from within the Japanese American community itself. Traumatized by their incarceration, many Japanese Americans simply wanted to forget and feared a similar racist backlash that had victimized them before.

But in the late ’70s and ’80s, the tide slowly turned. Cherry and her colleagues organized events dramatically demonstrating that the Japanese American community supported some form of justice. In 1978, the first pilgrimage was held to the Puyallup site where Puget Sound Japanese Americans were detained in 1942 before being moved to Idaho. The expected turnout was 500. Instead, 2,000 community members formed a long car caravan from Seattle to Puyallup.

Cherry and her committee organized hearings where internees could tell their experiences to touring U.S. congressional representatives. Heart-rending stories of lost and ruined lives and horrific treatment came out that had never been told. They formed an immense body of testimony of the human cost of government-sponsored racism.

In 1988, a bill finally went before Congress to apologize for the incarceration and provide $20,000 to surviving internees. Cherry was part of a dramatic final moment of lobbying before the vote on the redress legislation. She and two other activists were in the Washington, D.C., office of a conservative Washington state congressman who opposed the bill. After the polished presentation, the congressman replied that the answer was still “no.”

Getting up to leave, Cherry stopped, turned around in the doorway and said, “When it comes time to vote, please remember that for no other reason, you should vote for the redress bill because it’s the right thing to do.”

The next day, she turned on C-SPAN to see the same congressman speaking in the House floor debate, saying, “I have thought about this with my mind for a long time, and until this week, I was undecided, but when I turned to my heart I realized this is what has got to be done. Let us do it because it is the right thing to do.”

The measure was approved by Congress and signed by President Ronald Reagan.

My message for future educational leaders speaks to Cherry’s story. First, social justice requires dogged persistence and the courage to resist the status quo. Second, to move people to “do the right thing,” it’s important to appeal not just to logic and reason but also to the heart. And to do so with a simple and powerful story.

We’re living at a time when detention camps line our southern U.S. border. Americans of Iranian descent have been detained at the northern border. Muslims from certain countries are banned from entering the United States not because of any evidence of wrongdoing but simply because of their racial and national origin.

In this day and age, what can we learn from those like Cherry Kinoshita, who not only endured injustice but stood up against it?

Kyle Kinoshita grew up in the Seattle area and is a former teacher, principal and school district leader. Read about the Leadership Development for Educators Program. Parts of Cherry Kinoshita’s story appear in the book “Born in Seattle” by Bob Shimabukuro. The Day of Remembrance, Feb. 19, marks the day in 1942 that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, incarcerating Japanese Americans during World War II.