By Douglas Esser

University of Washington Bothell students are trying to ensure Seattle residents can breathe easier when a pall of wildfire smoke falls over the city.

Alex Margarito and Rebecca Rickett are working for Seattle Parks and Recreation this summer through a partnership with air quality expert Dan Jaffe, a professor of environmental chemistry and chair of the Physical Sciences Division in the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics.

Jaffe’s students are monitoring air quality and analyzing the data as part of a city pilot project to offer residents a fresh air oasis at some community centers. In announcing the pilot in June, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan said summer wildfire smoke could become the new normal. Air quality reached the “unhealthy for all” stage in the city for two days in 2017 and four days in 2018, Durkan said.

Smoke, in particular

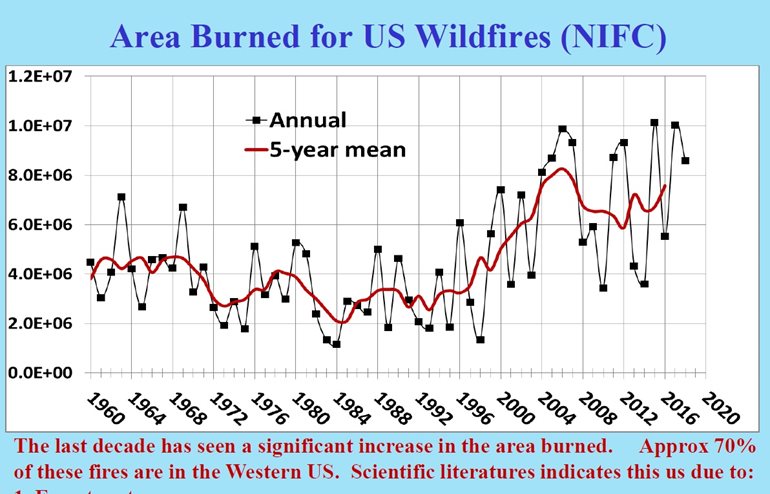

“The last two years have been the worst years on record in the West,” Jaffe said, noting that the student research will give the city better information about health risks, air monitoring equipment and benefits of enhanced filtering.

Smoke is a health concern because particulate matter (PM) inhibits the ability of the lungs to transfer oxygen, and that makes the heart work harder. There’s evidence that cardiovascular deaths go up during periods of extreme air pollution, Jaffe said. Experts typically advise that the old, the ill and other sensitive groups remain indoors during times of poor air quality. But, closing doors and windows may not be sufficient.

An expert on global transport of air pollutants, Jaffe was struck by the effect of wildfire smoke on indoor air in August 2018, when smoke from distant wildfires wafted over the Puget Sound region. Air quality reached an unhealthy level not only outside but also inside his office and his home.

“I study smoke. I study smoke outside. Last year was really bad,” Jaffe said. “Smoke was in Discovery Hall. Smoke was in my own home.”

Start with sound data

Margarito was in an atmospheric chemistry course with Jaffe and became part of his research group. “As soon as we started getting these wildfires, the first thing my brain went to is the chemistry,” he said. “What’s in the air? What concentration is that? What is this going to do to your body?”

Margarito took some of the measurements on campus and was surprised to discover the inside air was bad. The smoke wasn’t visible in a small space.

“You couldn’t tell that it was that bad inside until you actually took the measurements,” he said. “What we found is that the air inside buildings eventually can get near the same levels as what’s outside. So, sitting inside is not going to do that well for you,” Margarito said.

The summer research for the city is especially fulfilling for Margarito who graduated in June with a Bachelor of Arts in Chemistry: The work connects with his education and advances him toward his goal of becoming a high school chemistry teacher.

“What I’m doing with the project is finding out what works and then telling people. That’s what I have a passion for — education,” Margarito said. “I think it’s in line with UW Bothell’s values, because they’re all about protecting the community and the environment. The pieces fell in place.”

And more data

Rickett, who is finishing up a degree in Biochemistry, also was part of Jaffe’s research group. She had a capstone project in the spring comparing readings from a scientific air monitor device with readings from more affordable consumer electronic sensors made by Purple Air, a leading manufacturer.

When calibrated to correlate with official readings from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and interpreted correctly, the Purple Air sensors are good enough to track air quality trends, Jaffe believes.

Joelle Hammerstad, sustainable operations manager at Seattle Parks and Recreation, had already ordered 10 Purple Air sensors and was looking for students to analyze data when she connected with Jaffe at a conference.

“I had no idea how complex that process was,” Hammerstad said. “I’m bowled over by how intelligent, hardworking and passionate those young people are, and I’m so excited that Dr. Jaffe is open to partnering with us.”

Monitoring, analyzing

Anticipating a repeat of August’s unhealthy air episode, the city enhanced filtering at three buildings at the Seattle Center and at two community centers: the International District / Chinatown Community Center near downtown and the Rainier Beach Community Center in the southeast part of the city. Sensors are in place inside and outside.

To gather additional data and for comparison purposes, sensors also are in place at the South Park Community Center in southwest Seattle as well as at a Parks and Recreation office and warehouse, also in the southwest part of the city in an industrial area along the Duwamish River.

“Bigger picture, we’re trying to understand the situation at our facilities when we have poor air quality,” Hammerstad said. “Are the measures effective?”

The data also may inform the agency’s role as an employer. “As an organization that has hundreds of employees who work outside in summer, we’re trying to understand the impact for our staff,” she said.

At this point, the city is looking beyond attempts to mitigate greenhouse gases and to help those who are most affected, Hammerstad said.

“This is a critical, pivotal moment where we’re refocusing how we’re thinking about climate change. We’re thinking about resilience, adaption,” she said. “How do we help our community get through this?

“And really important, how do we help front-line communities get through this — communities that don’t have the resources to easily adapt to a changing climate?”

By the numbers

Officials are concerned with fine smoke particles 2.5 microns in diameter or smaller, which can move deep into the lungs. A micron is one-millionth of a meter. By comparison, a hair is about 70 microns wide. Particulate matter is measured in micrograms per cubic meter of air. A microgram is one-millionth of a gram. For example, a grain of salt weighs about 30 micrograms.

PM2.5 is considered unhealthy for sensitive groups when it rises above 35 micrograms per cubic meter in a 24-hour period. A person breathes about 11 cubic meters of air a day. The “unhealthy for all” PM2.5 level is above 55; very unhealthy above 150; and hazardous above 250, according to the EPA.

On Aug. 21, 2018, the level reached 110 in Seattle, the worst-ever PM2.5 measured in the city. On Aug. 22, 2018, Jaffe measured PM2.5 on the UW Bothell campus at 130 and about 100 inside his office in Discovery Hall.

If another smoke cloud threatens, carbon-pleated air filters will be installed in Discovery Hall’s ventilation system, said Tony Guerrero, associate vice chancellor for UW Bothell Facilities Services and Campus Operations. Other buildings on campus can keep out smoke by recirculating indoor air, but Discovery Hall draws in outside air because of its science labs, Guerrero said.

PM2.5 is one of five criteria measured for the commonly reported Air Quality Index (AQI). It rates air quality on a scale of 0 to 500, with 500 the worst. The four other AQI pollutants regulated under the Clean Air Act are ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide.

Because of the multiple pollutants in the AQI, its numbers don’t correlate directly with the PM2.5 figures. The AQI enters unhealthy territory at a value of 100.

Is it just me or is it climate change?

It’s difficult to directly link climate change and wildfires, Jaffe said, but it is one factor, along with forest management practices.

“The new normal is kind of a tricky phrase because we may or may not get smoke events this summer. It’s not going to happen every single year, but it definitely is happening with greater frequency than it ever happened before,” Jaffe said.

“We’ve just got to keep going with the research to understand how we mitigate these things,” he said. “Climate change is not going away.”