By Douglas Esser

The Rover Games began this year at the University of Washington Bothell. May the odds be ever in favor of the friendly gray hats, who hack the limits of operational cybersecurity without the malevolent intent of the black hats.

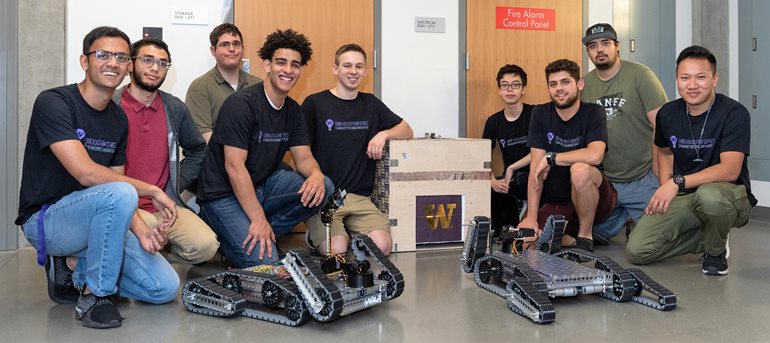

The games started as the 2019 capstone project for four Mechanical Engineering seniors under faculty adviser Pierre D. Mourad, a professor in the Engineering & Mathematics Division of the School of Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics. Mourad said it’s one of the most complex capstone projects he’s advised.

The games also include electrical engineering and computer science students and involve robotic rovers, puzzle boxes, hacking and cybersecurity. And just for fun, the rovers also race across an obstacle course and up a set of stairs.

Original design

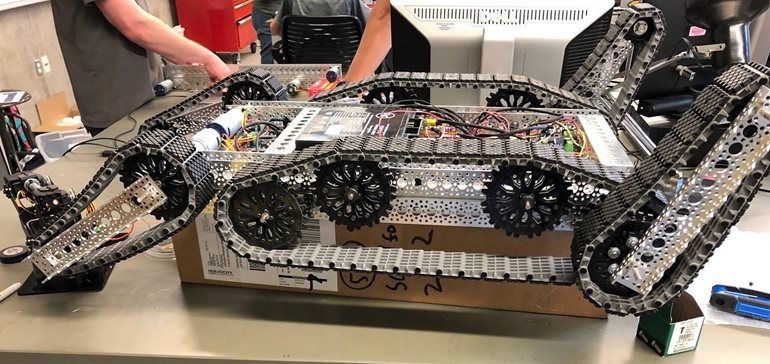

The mechanical engineers started by designing, building and programming four rovers. Each is about 2 feet wide and 3 feet long, with a robotic arm more than a foot tall with a camera on the end. The rover is powered by a motor-bike battery that drives the black treads.

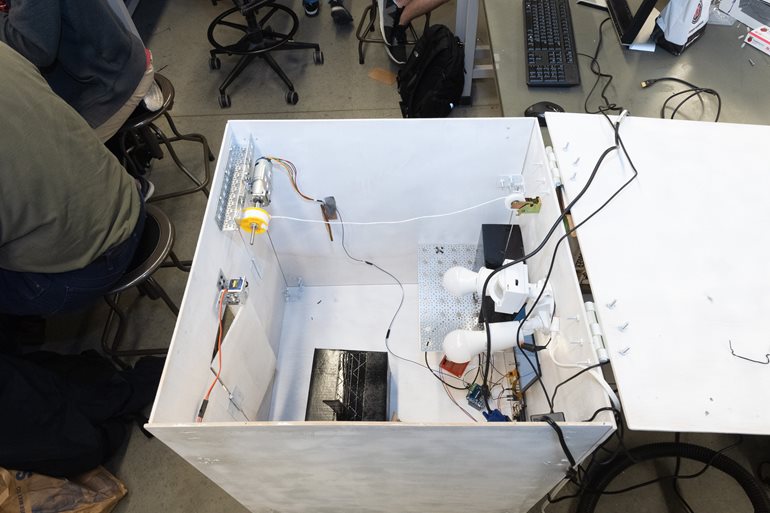

Other students designed and built four puzzle boxes. Each is about the size of a minifridge, with doors or windows. Inside each box are four pieces of a puzzle, which when assembled creates an image. Each box also has different traps and obstacles.

The object of the game is for a rover to overcome the obstacles with its robotic arm and take photos of the four pieces. The winner collects all 16 pieces and identifies the image.

Sounds easy doesn’t it? Not so fast. Everything runs on Wi-Fi and can be hacked. Each team has to deal with the other teams trying to disable the other rovers, disarm traps and steal puzzle images.

“There are people on each side of a device. Some of them are defending it from a cyberattack, and some of them are proceeding with a cyberattack,” Mourad said.

Ultimately, both sides are gray hats, practicing cybersecurity.

Protecting operations

Mourad intended the complexities and vulnerabilities to challenge students with problems of operational technology. The cybersecurity, in this case, doesn’t protect information. It protects how things run.

“The bad people — the black hats — want to hack mechanical-electrical systems, for example, the power grid,” Mourad said. “Automated and semi-automated manufacturing processes, they’re also hackable.”

The Rover Games are sponsored by the university’s Center for Information Assurance and Cybersecurity (CIAC). Executive Director Barbara Endicott-Popovsky is investing in a multiyear sandbox for hacking competitions. “We applaud Dr. Mourad for his advocacy and support of student experiential learning. We’re very proud of the results,” Endicott-Popovsky said.

“Having a sandbox for a hackathon — a place to play that involves all those systems — is vital for today’s needs and tomorrow’s needs,” Mourad said.

Winning isn’t everything

The students played their first Rover Games June 13 outside the mechanical engineering lab in Discovery Hall, within a protected portion of the Wi-Fi system constructed by Computer Engineering student Geoffrey Powell-Isom. Rovers probed puzzle boxes, sometimes stalling under an attack. No one successfully collected all 16 pieces of the puzzle. The seniors presented their work June 14 at the STEM Capstone Colloquium in the Activities & Recreation Center.

Mourad expects the Rover Games will become more complex and involve more students each quarter. By next year, Mourad would like to see semi-autonomous robots with onboard artificial intelligence climbing the stairs and attacking puzzle boxes all over Discovery Hall. Mourad also would like to hold multicampus Rover Games that remotely involve the UW campuses in Seattle and Tacoma as well as colleagues in Dublin, Ireland.

“As more rovers and puzzle boxes go online, we’ll have more people doing this,” said Mourad.

“This is going to get crazy in a few years, I’m sure,” said Brandon Barkauskas, one of the students who built the rovers. The others are Alnur Elberier, Kuber Motgi and Thu Yein. All graduated this June, except Elberier, who has one more quarter in the fall to complete a second degree in Computer Engineering.

Smoke and burns

The capstone was a real-life experience that put theory into practice.

“This is the first time I’ve really built and designed my own functional circuits,” said Elberier. “I’ve fried stuff, and I’ve seen smoke come out of the rover, and I’ve burned my hands with solder. It’s super rewarding when it finally works in the end.”

While in school, Elberier started working at his job at Boeing in cybersecurity for automated manufacturing. His manager visited campus to see a Rover Games presentation.

After graduating, Barkauskas, who has management experience, is looking for a position in project management. Yein is going to work for an aerospace metals fabrication company. Motgi has an internship with a company that makes biomedical devices.

Disco 270

The four figured they put about 2,000 hours into their project, which demanded more than mechanical engineering skills. They ordered about 300 parts. They updated reports. They coordinated with as many as 16 other students who had a hand in the puzzle boxes and hacking.

Late nights in the mechanical engineering lab, Discovery Hall 270, with other students working on their capstones and playing music soon became a community, they said. Everyone wanted to see the other projects come together.

“It’s just a great experience to work together and achieve success,” Motgi said. “That’s what I learned from this project.”