By Douglas Esser

Tuberculosis, a disease now usually controlled by antibiotics, is not so far removed in time or distance.

UW Bothell students learned this firsthand in two fall courses on infectious disease and quarantine when they toured the former Firland sanatorium in Shoreline, Washington, where from 1911 to 1947 TB patients in King County were isolated.

“I think it’s very important with a lot of our health issues today to look how we handled them in the past, especially with tuberculosis because it’s coming back,” said Stefanie Iverson Cabral, a lecturer in the School of Nursing & Health Studies.

Questions of isolation, quarantine and the stigma attached to some diseases remain relevant as people decide how threats to public health balance with patient rights.

“You wonder, is it to actually make them better or is it to make the rest of us feel safer?” asks Iverson Cabral, who arranged the tour for her students.

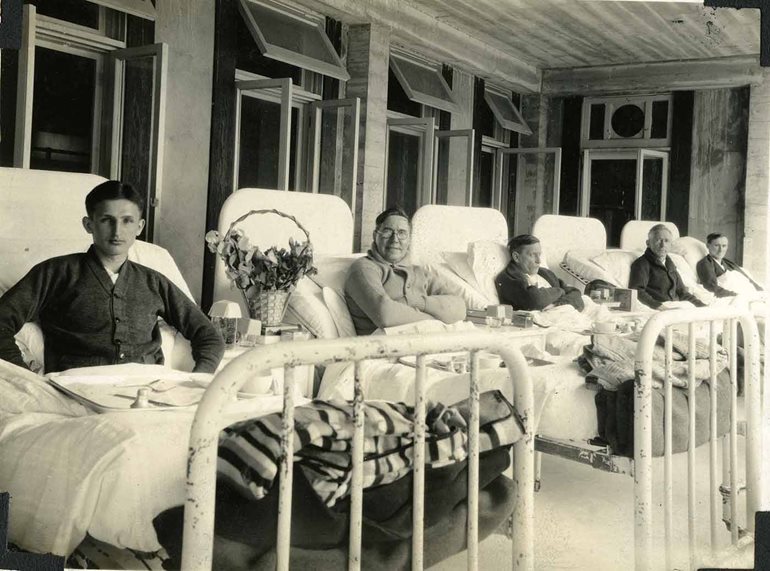

Collection of Washington State Historical Society, Catalog ID Number 2003.188.67.40.

Sanatorium sights

Students saw some of the places where the sanatorium treated TB patients with strict bed rest, cold air and surgeries that could include deflating a lung. Students also had to refer to historical photos and use their imagination because the buildings are now part of the campus for CRISTA Ministries, which operates schools, broadcast stations, senior communities, camps and global development services.

Iverson Cabral connected with the Shoreline Historical Society and CRISTA for the rare opportunity to walk through the buildings.

“We were able to see the underground tunnels that were used to transport patients and supplies, which was an interesting way to see how the space was utilized,” said Mariah Kunz, a Health Studies major graduating in June.

Although the campus has a completely different use these days, it was clear how those with tuberculosis were kept separate from the public, said Kunz, who is interested in how social conditions affect diseases.

“A big component of how disease spreads is whether people are afraid to admit that they are infected and seek treatment,” said Kunz, who hopes to attend the UW’s School of Public Health for a master’s degree and eventually work in health policy. “Treating patients with respect and dignity should always be a priority, and society benefits from empathy.”

‘The Plague and I’

The tour was part of two courses: a 400-level online elective about quarantines and a 200-level science requirement. Students in the upper-level class were required to read “The Plague and I,” a memoir by one of Firland’s most famous patients, Betty MacDonald.

MacDonald was a best-selling author in the 1940s and ’50s who wrote “The Egg and I” and the “Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle” series of children’s books. In “The Plague and I,” she wrote about stigma and her feelings of isolation.

A lecturer at UW Bothell since 2015, Iverson Cabral explores stigma and other ethical issues, which make her courses valuable to students interested in law, government and policy as well as health studies.

TB then and now

TB is a bacterial infection spread through the air, often by coughing. It usually attacks the lungs but can affect any part of the body, causing fever, chills, weakness and weight loss. It was previously known as consumption because it seemed to “consume” the body or as the white plague because of patients’ extreme pallor.

One early theory of treatment was that TB was an injury to the lungs, analogous to a broken leg. As one needed to stay off a broken leg, one needed strict bed rest so the lungs could recover. People who were reluctant to follow the rules were made to feel they were responsible if they failed to get better. Blame was part of the stigma that TB was also, in some way, a character flaw, Iverson Cabral said.

Difficult to diagnose, tuberculosis was once a leading cause of death in the United States and remains a significant disease. There were 528 U.S. deaths in 2016 and 9,105 cases reported in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Globally, tuberculosis remains an epidemic and one of the top causes of death, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). About one-quarter of the world’s population is infected with TB, although not everyone who is infected becomes ill, thanks to their immune systems. Of growing concern are drug-resistant forms of TB and the risk to people with untreated HIV who have weakened immune systems. In 2017, according to WHO, tuberculosis killed 1.6 million people, including 230,000 children and 300,000 people with HIV.

Stigma vs. science

courtesy photo

When a serious disease is easily spread through the air, what are we going to do in the “post-antibiotic era”? asks Iverson Cabral.

“Are we going to go back to a system like this where we take people who have TB and put them away?”

For students who may face such questions, it’s important to understand science as well as history.

“How can we make the best choices — where we balance the health of the public versus the civil rights of the individual, where we don’t make a lot of the mistakes we made before?” Iverson Cabral asks. “I’m a big proponent of knowing what we did in the past — what was good about it, what was bad about it — and how we can navigate that better in the future.”

A lot of people are surprised that diseases such as TB are still around. Or they may be scared by headlines about Ebola or Zika and the hysteria that goes with them.

“Real risk versus perceived risk is something that I talk a lot about,” said Iverson Cabral. “Let’s be very good consumers of science.”

The Stop TB Partnership raises awareness on World TB Day March 24.