By Zachary Nelson

John Bridge, associate professor of mechanical engineering, is an international expert in monitoring the quality and consistency of synthetic materials used in horse racetracks. The more consistent the track materials, he says, the safer the racetracks are for jockeys and horses.

“I have been doing R&D for over 20 years, and it is always great to work on research that will improve people’s lives,” Bridge said. “We were also able to turn vets' attention to the types of injuries that result from the synthetic surfaces as well, so that they can prevent more horses from being euthanized due to track-related injuries.”

Traditionally, tracks are made from natural materials such as sand and dirt that are oftentimes specific to the particular geographic region. Research has shown, however, that synthetic materials are safer for horses (many worth millions of dollars) to race on and can significantly reduce the rate of injury. These newer synthetic tracks are primarily made of silica sand, polymer fibers and rubber particulates, all coated with a wax/polymeric binder.

“Our research is conducted in collaboration with the Racing Surfaces Testing Laboratory (RSTL) in Kentucky that tests both conventional and synthetic tracks worldwide," said Bridge, who teaches in the School of STEM’s division of engineering and mathematics and is a former RSTL researcher.

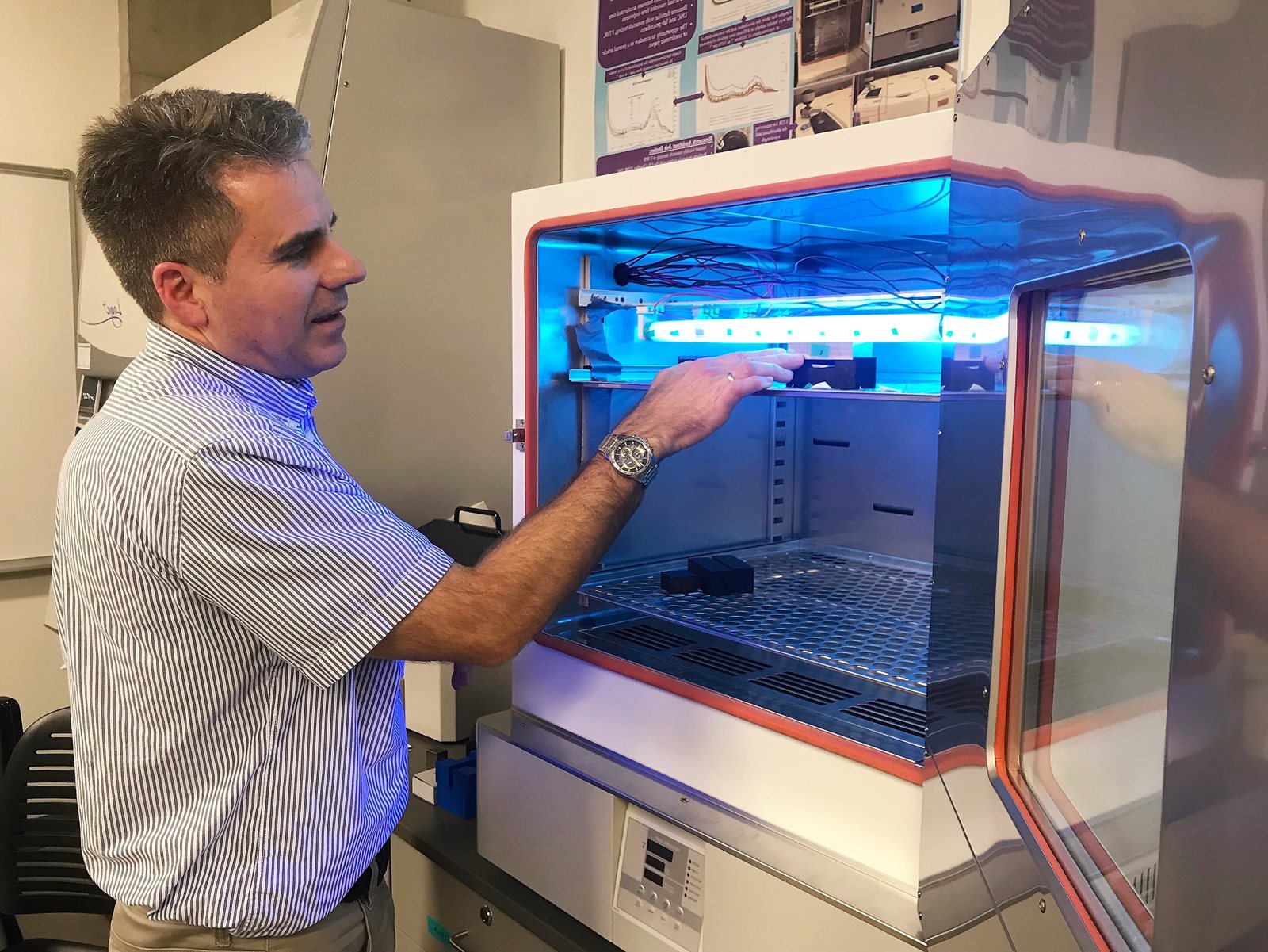

John Bridge and the degredation chamber.

Bridge works in the lab with students to analyze this data and create reports for the racetracks about how their synthetic tracks are holding up and what they could do to improve certain properties and consistency. Track owners can look at this report and see how any short-term modifications to the track, as well as maintenance actions, have affected the track surfaces."We receive synthetic track samples taken from operational racetracks and are able extract the components and apply various analytical test methods to obtain insight on chemical, thermal, and mechanical properties. We can then use that information to draw conclusions concerning the mechanical performance of different track surfaces over time."

But the longer-term durability of these materials is still an important part of the needed research so the students in Bridge's team created an "ultraviolet environmental degradation chamber" to further break down the materials. This machine, which looks like an oven, simulates seven years of weathering on the surfaces in just four days.

The students and professor also use several other machines to conduct research. In their lab, they test the composition of the polymer materials using Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) in combination with a Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC).

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is also available down the hall and used to gain further insight into the chemical structures of the rubber particulate and other components. Gas chromatography (GC) is used at a local company to further understand the molecular makeup of the wax/polymer binder and how it changes over time. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is also used (at UW in Seattle) to study wear and fracture surfaces of the track components. Students are trained to run all the tests.

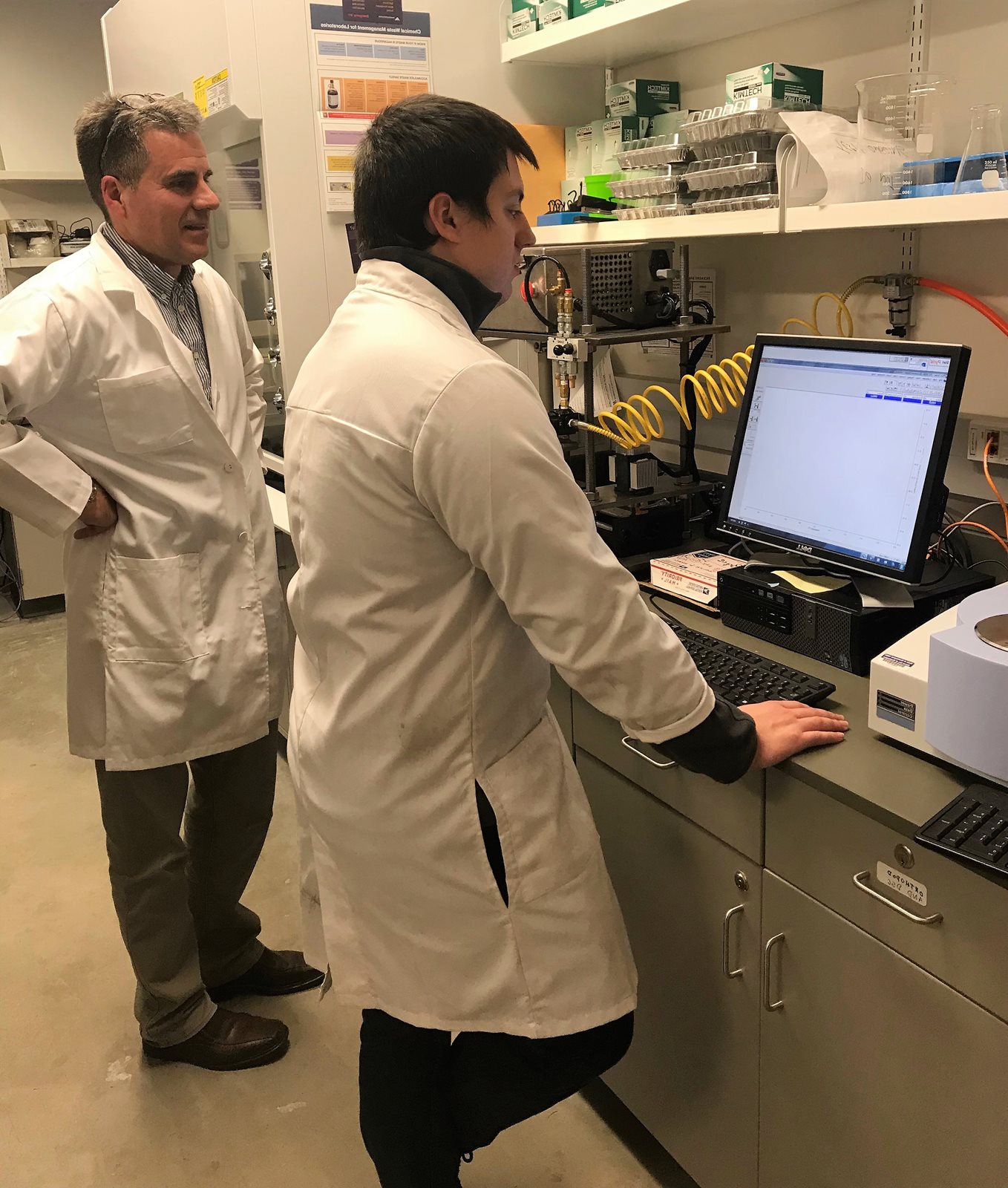

John Bridge mentors Bryce Denis.

For example, the FTIR machine analyzes samples to generate a snapshot of what is actually in the material submitted by the racetracks — particularly the type of fiber and polymer binder. FTIR can also be used to quantify UV degradation and oxidation. Next, the DCS machine gauges the heat capacities of the samples as well as their melting temperatures. The researchers can then use this additional information to gain greater insight into what materials work well in a track environment.

“I love learning how the machines work and finding the results," said Bryce Denis, a mechanical engineering student and lab manager. He says he is fascinated by synthetic materials, which is why he has spent so much of his time as a student in Bridge's lab conducting research on racetracks.

"It gives me a sense of accomplishment to know that I am discovering data that nobody ever has before," he said. "Four years ago, I was a freshman looking for research to partake in, and I was able to join a lab immediately. I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to this amazing work,” Denis said.

His work was also recognized by a nearby materials characterization laboratory, LabCor LLC, where he now works. “I received an internship with LabCor because of my work in UW Bothell’s lab,” he said. “I love that work I started as a freshman has become the start of my career as a senior.”