Story by Douglas Esser

Photos by Marc Studer

University of Washington Bothell lead gardener Tyson Kemper once discovered a new plant species.

Kemper, right, scored the rare scientific achievement more than a decade ago while exploring the wilds of Idaho and collecting plants, in the tradition of Lewis and Clark, for the University of Idaho herbarium (a plant library).

He found a member of the carrot family like none that had ever been described before.

Lomatium brunsfeldianum, also known as Brunsfeld’s desert parsley, belongs to a group of edible plants common to parts of Idaho and eastern Oregon. The plants were used by Native Americans and commonly known by residents as biscuit root.

“It’s not that they didn’t already know about it,” says Kemper, who named the plant after his adviser Steve Brunsfeld.

It was a discovery in the sense it was a new “type species.” The Latin name, the rigorous description and the details of its location were entered in a centuries-old classification system maintained by herbaria around the world. Kemper invented a bit of knowledge.

“The herbarium creates taxonomy for plants, and then we know what we’re looking at and can share that information,” Kemper says.

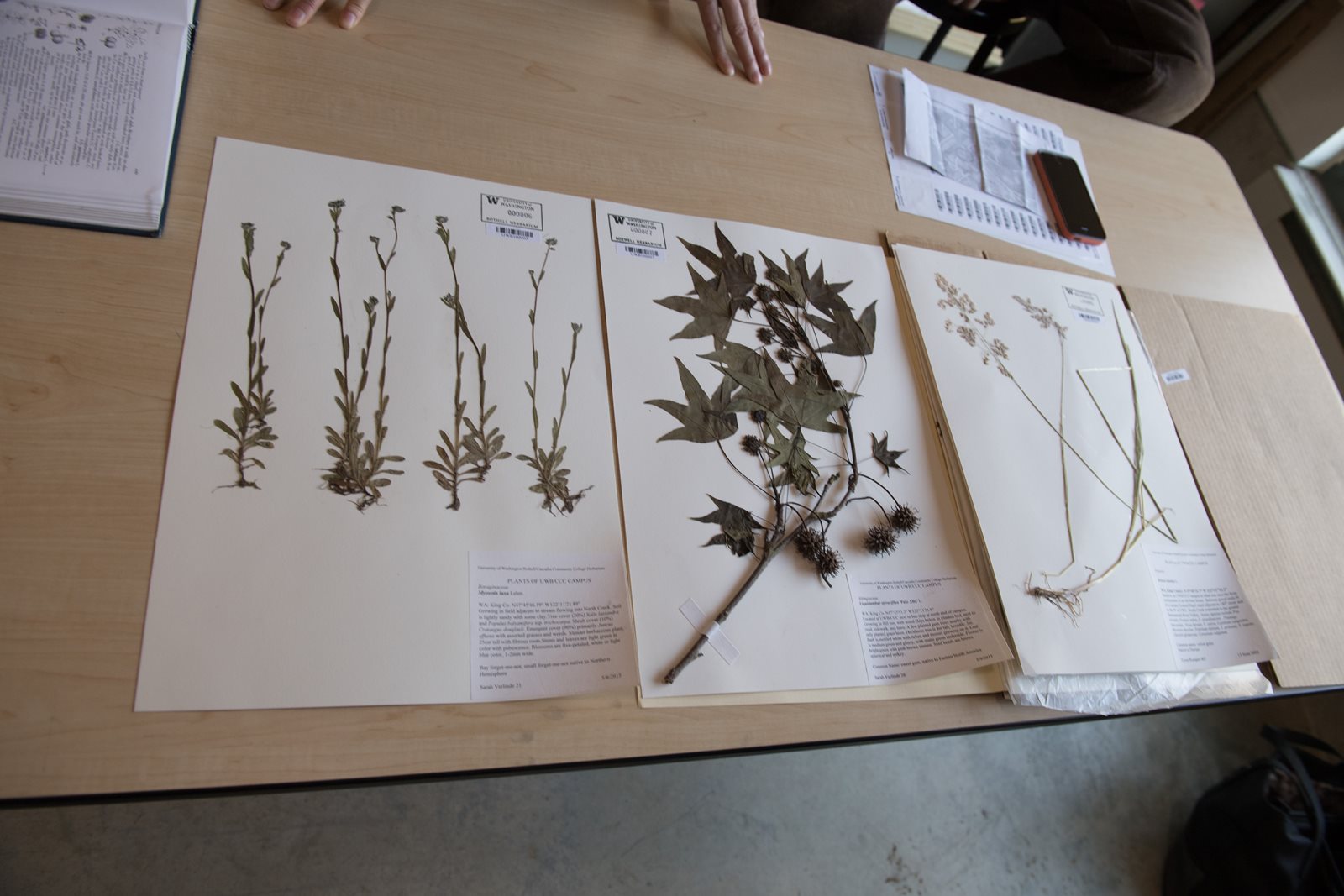

That’s the value of a herbarium, a word that refers both to the collection and the place where specimens are pressed, dried and identified. Universities and botanical institutions maintain them, taking plants from dirt to digital.

Now, a small herbarium has sprouted at the University of Washington Bothell. It’s growing under the care of Kemper, the University’s office of research and faculty.

UW Bothell’s herbarium provides a critical authoritative record of plants occurring in the 58-acre campus wetland and the surrounding landscape, says Warren Gold, associate professor of environmental science and director of the University of Washington Restoration Ecology Network.

“As the vegetation changes through time in the wetland it will form a reliable record to help us and future researchers understand biological and habitat change in one of our regions’ pre-eminent floodplain restoration projects,” Gold says.

The herbarium is also a valuable resource for classes such as BES 490 (Pacific Northwest Plants), BBIO 471 (Plant Ecology) and BES 316 (Ecological Methods). Students use the herbarium to identify plants and practice careful scientific documentation.

“This herbarium is already playing an important role in fulfilling the mission of the Sarah Simonds Green Conservatory to foster research and educate students and the general public about the natural world in our region,” Gold says.

Kemper credits Caren Crandell with planting the seed for the UW Bothell Herbarium. A lecturer in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences who teaches wetlands ecology, she donated some of her own money to get things started, Kemper says.

With her funds, Crandell says one of her wetland students, Cindy Easterson, started the herbarium as a community engagement project and was the first collector. Crandell’s students use the herbarium for her wetland ecology and native plants classes. Herbarium experience is unusual for undergrads.

“The botanical knowledge and other technical skills associated with herbarium work help their resumes stand out as they begin their job searches after graduation,” Crandell says.

The herbarium, located in the conservatory, received an energy boost in the past year under the administration of Sarah Verlinde, left, of the office of research. The 2015 UW Bothell graduate in biology studied under Crandell. Verlinde also trained at the Otis Douglas Hyde Herbarium at the UW in Seattle under curator Eve Rickenbaker. (This herbarium also has donated specimens to UW Bothell.)

Now, Verlinde is applying to have the UW Bothell Herbarium recognized with the Index Herbariorum, the international directory managed by the New York Botanical Garden. It accredits more than 3,400 herbaria in the world with about 350 million specimens, documenting the earth’s vegetation for the past 400 years.

The UW Bothell Herbarium will be posted online with the Pacific Northwest Herbarium Consortium. The Burke Herbarium at the UW in Seattle has offered server space. Collections manager David Giblin is giving Verlinde advice, and botanist Ben Legler is helping set up the database.

The herbarium is “institutional infrastructure” for studies of conservation, ecology, biodiversity, extinction, invasive plants and climate change, Verlinde says. It will serve taxonomists, biologists, ecologists and horticulturists around the globe.

Kemper, who earned bachelor’s degrees in botany and English at the University of Washington in Seattle and a master’s in evolutionary ecology at the University of Idaho, remains on the lookout for new species. While it’s unlikely one will be found in the wetlands, there is a good possibility they could support rare plants, he says.

In addition to his labors in the wetlands and campus landscaping, Kemper also works with independent study students. Photo: Plant specimens are pressed between sheets of paper and cardboard.

“That’s why this place has been such a good fit for me because I can use both sides of my brain – to be able to educate as well as dig in the dirt – so important.” Tyson says. “Not bad for a gardener.”