By Douglas Esser

Ever since Gary Carpenter started teaching art classes at the University of Washington Bothell in 2011 he’s always looked for opportunities to engage his students in the community around them.

Exploring the use of the arts in social change, the lecturer in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences once brought homeless people and homeless advocates to a class to share their experiences and answer questions. Another time the class visited a tent city where students shared a meal and were impressed by the self-governance and sense of community they found.

A strong believer in the role of empathy in the classroom, Carpenter, right, says these mutually beneficial experiences, “when framed thoughtfully, can lead to a much different way of viewing the world, privilege and social inequity.”

The culmination of that progression was the Arts of Social Transformation class Carpenter taught the past three springs inside the walls at the Monroe Correctional Complex. Half the classmates were prison inmates.

“It was the most engagement, the most immersive,” says Carpenter.

University behind bars

Inmates for the class were screened and enrolled by the Seattle nonprofit University Beyond Bars, which is not offering the service this academic year. Carpenter hopes to teach the class again next year. While he is planning to replace the winter quarter Arts of Social Transformation class with another high impact reciprocal learning experience, he's also developing a community based learning class for Discovery Core that will explore similar issues to those covered at the prison.

The original class took a special group. Students had to be 21 or older and needed a certain level of maturity and emotional stability. They weren’t going to the prison as tourists.

A percentage of prospective students were interested because they have a relative in prison. Others applied because of a career interest in community psychology, social work or the legal system.

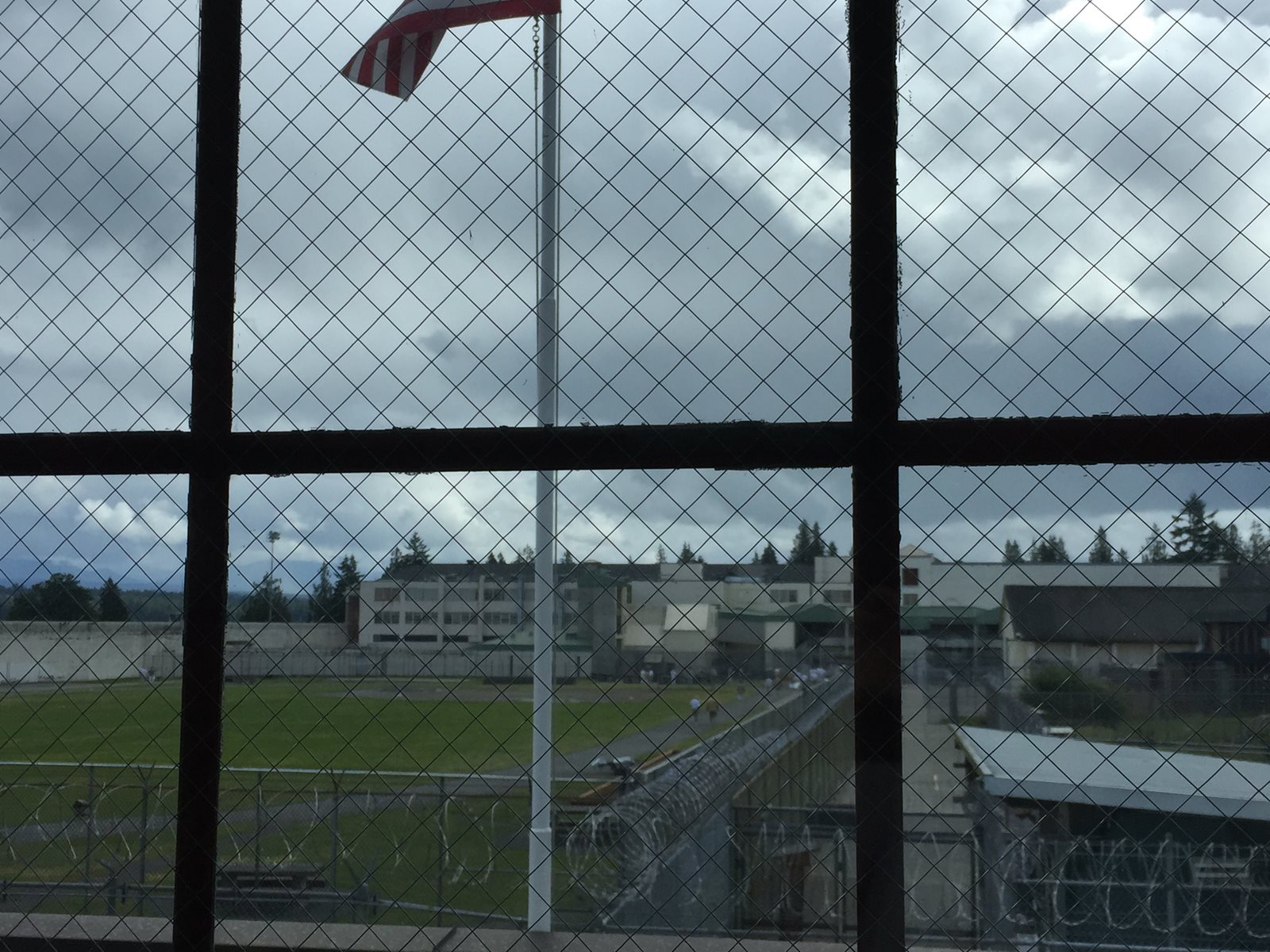

Students had to commit to the class early to allow time for a background check and training required by the state Department of Corrections. Considered volunteers, students were trained for situations they might encounter, including worst-case violence.

Why can’t you wear a scarf? Because it could be used as a weapon.

A class of big ideas

An art class typically brings up images of drawing, painting or sculpting with clay. But prison limits the materials. For example, clay can’t be used because someone might use it to jam a lock or take an impression of a key. Colored paper might be used to counterfeit a badge. So, students used only plain white paper and pencils, which is all they needed to collaborate on big ideas.

Arts of Social Transformation was a five-credit, 400-level course that used small group discussions to explore social issues related to real public art proposals that Carpenter found on the internet.

Student-inmate anxiety

Once a week during the quarter UW Bothell students traveled to Monroe and passed through security checkpoints to meet with inmates in a room resembling a classroom.

“I would say the most scary or intimidating part is actually going through the process of getting a name tag and going through security,” said Jasmine Giles, left, a student in last spring’s class who graduated with a degree in society, ethics and human behavior.

On the other side, inmates were a bit intimidated by university students, Carpenter said. They wanted to meet on that level, so they prepared.

Prisoners were willing to have personal, in-depth discussions about topics such as bullying, privilege and social change, said Kelsey Bolinger, right, a member of the spring class who graduated with a degree in society, ethics and human behavior.

“Everyone in this atmosphere was so much more open to that from day one,” she said. “For us, our mindset had to be on. We had to be ready to work.”

Benefits for inmates, prison

By the end of the quarter the UW Bothell students had exchanged a wealth of information about their experiences and cultural backgrounds.

“When we have these discussions about social issues and the arts they’re so rich that the student are always having these “Aha! moments” where they’re seeing things from a different perspective,” Carpenter said.

There was a lot of learning for both University and inside students, said Susan Biller, spokeswoman for the Monroe Correctional Complex. Some inmates looked forward to using their education after their release. Others with long sentences gained perspective.

Education also is the single most effective way to reduce recidivism, the relapse into new crimes by old offenders, says University Beyond Bars.

Taking a class in a prison has been compared to study abroad – different culture, different rules, a lot of preparation.

“I’ve had people say, ‘Gary, is it worth it?’ It’s definitely worth it,” Carpenter says. “As an educator, when you can create that kind of an impact on students and realize the social benefit of what you’re doing, it’s so rewarding.”

It’s also worth it for the students, he says.

“These experience generate a great deal of contemplation and learning, and ultimately lead to changes in perception about social issues and hopefully impact these issues in the future,” Carpenter says.

Photo: Kara Adams, left, recognizes Gary Carpenter, and students Jasmine Giles and Anastasia Evangelista at 2016 Community Partner Celebration. (This photo and photos of Giles and Bolinger by Marc Studer.)